The kingdom of Benin, in what is now central Nigeria, was a powerful African state from the Middle Ages until its destruction and invasion by the British at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1897, the British army looted the treasures kept in Benin City and since then thousands of precious objects, mainly bronze and ivory, have been scattered to western countries.

The desideratum as well as various attempts to create an overview of the scattered royal treasures of Benin have existed for a long time and have been present in academic circles and in the demands of activists since the 1970s and 1980s. The concrete restitution policy initiated in Germany, in response to a long-standing Nigerian demand, has changed the working relationship between Nigerian and European partners in this field and made this project possible.

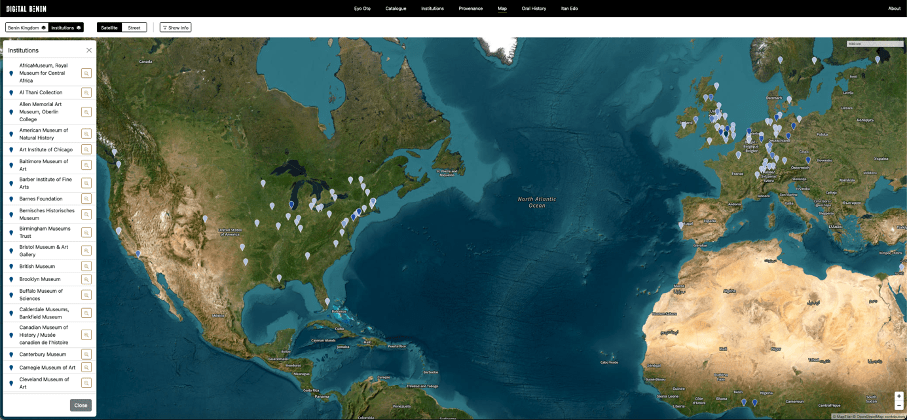

Although the project has been in the pipeline since 2010, the international team of the Digital Benin project, led by Felicity Bodenstein (Univ. Paris-4), Anna Luther (Institut for Digital Heritage) and Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner, director of the MARKK, has been very active since 2019 in order to bring together around 5000 objects belonging to this heritage, spread across 131 institutions and collections worldwide (mainly in the US, UK and Germany, see map below) into a single digital space .

The catalogue is the central tool of Digital Benin, one of the two digital spaces on the platform where the scattered Benin objects have been reassembled. It is possible to search, filter, study, and view the data of 5246 historical objects from the Benin Kingdom from 131 institutions in twenty countries.

This ambitious project was made possible by a three-year grant of €1.5 million from the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and the hosting of the project by the Museum am Rothenbaum – Kulturen und Künste der Welt (MARKK) in Hamburg.

I won’t go into the complex and intertwined scholarly and political aspects of this project, which are documented in Felicity Bodenstein’s long and excellent interview, recently published in Cahiers d’Etudes Africaine 2023/3-4 (n° 251-252).

Among the many challenges it faces, I’ve chosen to focus on the issue of metadata. Will this situation provide an answer to the perennial question: is metadata really interoperable? The answer is: forget everything you know about Dublin Core or whatever!

1. Testing interoperability on extremely heterogeneous datasets

131 institutions were asked to send the descriptions of their objects, together with images of each artefact and any available information documenting the history of their acquisition. In order to facilitate this process, those responsible for submitting the descriptions were not asked to restructure their metadata according to a uniform grid that Digital Benin would have superimposed on their existing metadata. On the contrary, Digital Benin undertook to publish each institution’s metadata as it was, both in its public form (what was already publicly available through the API) and in its internal form, sent directly by the institutions, if the two differed, see for example here.

And all these data sets were, of course, extremely heterogeneous: written in different languages, very long or very laconic, organised according to international description standards or home made, sent in Excel files, JSON, in Word files or in email content…

So how to make sense of all this and provide a tool that respects the diversity of metadata, but is still searchable and therefore has standardised fields and structure?

Gwenlyn Tiedemann and Anna Luther detailed in their documentation, “Data Acquisition and Data Management,” how the team acquired and documented data from institutions, and processed metadata. They emphasised that: “the backbone of the entire project is the object’s metadata” and “the main task was to bring heterogeneous dataset to a comparative level”.

The result is quite impressive. It allies a skillful engineering experience – in order to build the databases for processing the datasets – with as much imagination as pragmatism in order to gather the many diverse fields under common designations.

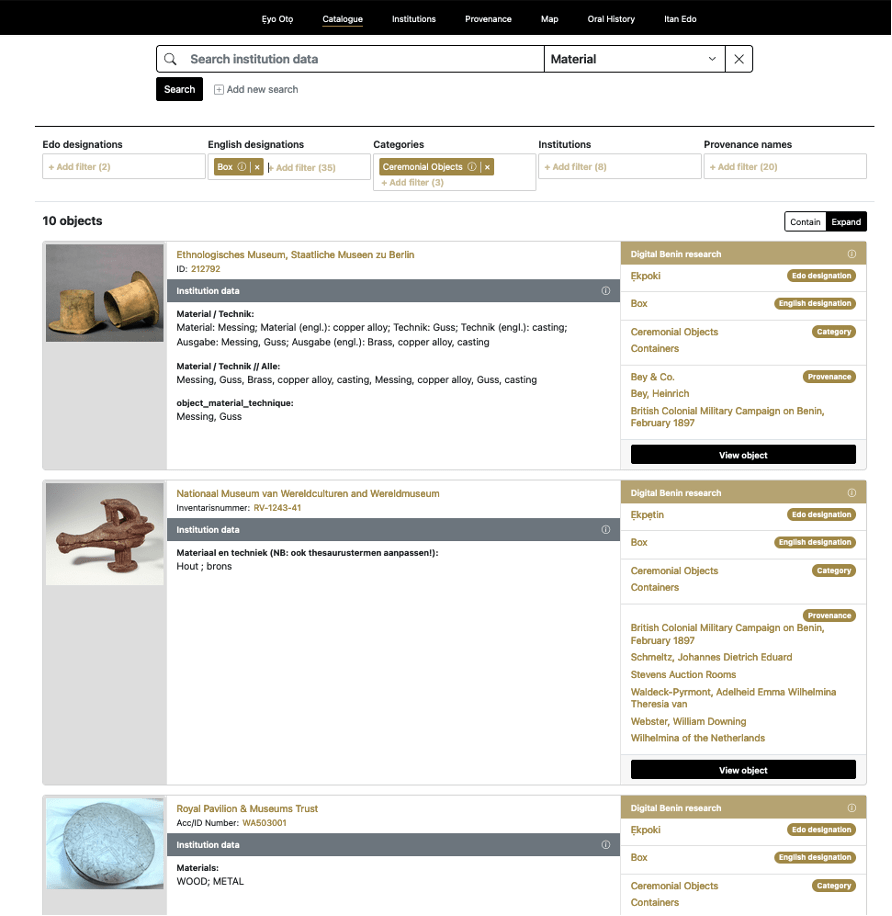

Indeed, there are numerous methods for searching the database, including a full-text search. And, in addition to this, users can choose from the “All fields” option, which consists of 36 field structures categorised into the following main divisions: “object information”, “object production”, “provenance”, “object context”, and “institution context”.

In the image below you can see research on the category ‘material’, which was also narrowed down to ‘ceremonial object’ and ‘box’. It displays the various metadata fields used by each institution.

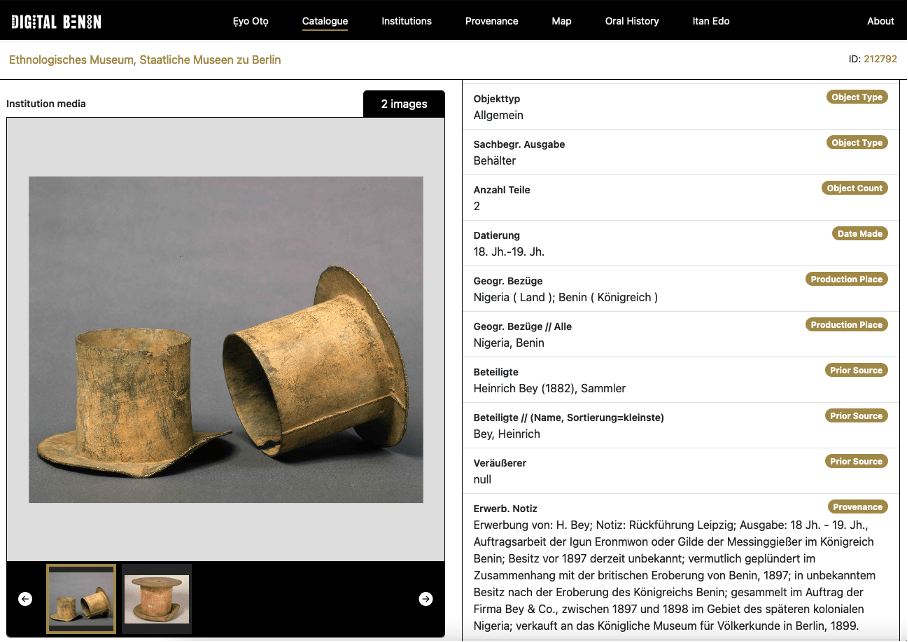

If the range of metadata received is still visible on the right-hand side of the screen in a beige colour, one can view the Digital Benin research. This displays the overall fields that have been combined from the many different fields provided by the institutions, as shown in the next screenshot:

In this notice provided by the Ethnologisches Museum of Berlin, there were two ways of quoting the country where the object was produced as well as two ways of writing the name of the first collector. They are compiled under a single label, and querying it will provide all relevant information.

The dispersal of the objects for many of them over a century and a half has resulted indeed in a vast array of designations.

2. The vernacular and the global

How should nomenclature be approached and what reference should be used, if any? Quite new in the field, at least to my knowledge, is the following initiative: the historical objects are displayed with their Edo name, which appears at the top of each research object and is also vocalised. The methodology for investigating these names is delineated in this piece by the socio-anthropologist Eiloghosa Obobaifo, who spearheaded the study.

The first Edo controlled vocabulary for historical Benin objects has been created by reviewing and editing the Edo language on the platform. This research category creates object groups that differ from vocabularies used and interpreted by institutions outside of Nigeria.

For example, the English term ‘anklet’ is only one of at least three different Edo terms visible here. This introduces a very different typology.

There is additional content which I won’t detail here. I’ll simply provide a list of resources related to Edo history, like a Christmas shopping list. These include oral tradition records, impressive data sourced only from Nigeria (which can be challenging to read due to multiple windows: https://digitalbenin.org/itan-edo), 3D models of objects provided by various institutions, and a bibliography, which is essential for any scientific work even though it might not feel like Christmas. Additionally, an animated short movie sketches the historical context of the 1897 British invasion and looting. All this provides an excellent setting for this ambitious project, which was conceptualised with Nigerian professionals and for the Nigerian communities and realised in only three years! Luckily, a new grant from the Mellon foundation, planned for 2024-2027, will allow the sustainability and development of this platform.