This is part one of a three-part series on the biases about the Hellenistic Central Asia in generative artificial intelligence (AI) datasets. Beyond the ethical issues surrounding the training, maintenance, and overuse of these tools, there are significant biases about the ancient world that bleed into AI-generated content. This is becoming ever clearer as tools become more complex and accessible. It is crucial that we all are aware of these biases and how they are formed to prevent the creation of skewed histories with problematic origins.

The first and most glaring use of generative AI involving Hellenistic Central Asia is AI-generated imagery. The history of Hellenistic Central Asia, much like most genres of history, is illustrated through this medium with very little regulation. Across most social media platforms, “History Facts” influencers are publishing posts and threads about figures, architectures, events, and geography in Hellenistic Central Asia and pairing these posts with AI-generated images.

Figure 1: X post by @PaginasFuriosas on September 26, 2024. The post features an AI-generated image that was likely created by DALL-E 3 (OpenAI). Available at: https://x.com/PaginasFuriosas/status/1839248190387708271. ©PaginasFuriosas.

The issue with these posts is two-fold. First, images are used to illustrate the stories discussed in these posts without proper attribution or explanation, leaving uninformed readers to draw conclusions about the images without context. Second, the images themselves have many modern biases in them, which are created by generative image AI’s weightings in their datasets.

It is quite easy to bias a generative image AI tool. Nightshade, a digital art protection tool created by a team at the University of Chicago, transforms an image file into “poison” samples. Essentially, much like their artist protection program Glaze, users can upload a digital image, and the tool then alters the image in a humanly imperceptible way. To a human, the image will look the same, but to an AI, the image looks like something completely different, such as a dog replaced with a cat, or a cow replaced with a purse. The primary purpose of this tool is to stop generative AI developers from using artworks without proper consent.

Figure 2: A visual representation of the impact of Nightshade-poisoned images on generative image AI models from Shan et al. “Nightshade: Prompt-Specific Poisoning Attacks on Text-to-Image Generative Models”, 2023. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.13828. ©Shan et al.

The Nightshade team found that 300 shaded images were enough to completely distort a generative image AI’s presentation of a concept. However, as few as 50 could have an impact. The “dog” in the above image is already strikingly similar to a lion cub with just 50 poisoned samples. Bearing this in mind, we have to consider how sheer numbers of datapoints can greatly skew how a generative image AI produces an image.

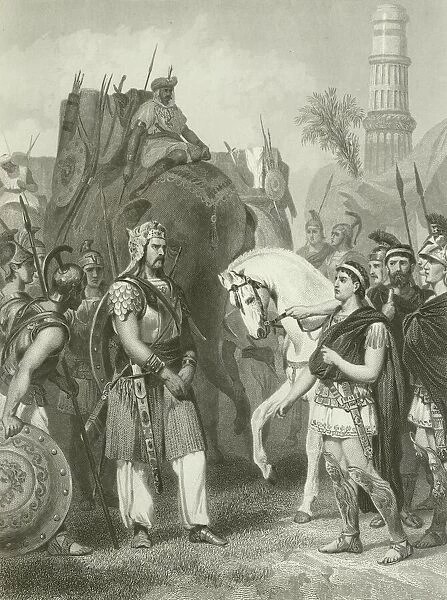

Looking at this image created for an article on historymarg.com, the generative AI has seemingly depicted the meeting of Alexander the Great (r. c. 336-323 BCE) and King Porus (r. c. 326-315 BCE), a ruler of the region between the Jhelum River and Chenab River in Northern Punjab, around 326 BCE.

Figure 3: An AI-generated image featured in Moreland and Chatterjee, “The Greeks in the Punjab (Ancient India)”, Historymarg.com, December 23, 2023. Available at: https://www.historymarg.com/2023/12/the-greeks-in-punjab-anciant-india.html?m=1. ©W. H. Moreland and Atul Chandra Chatterjee.

The presentation of Alexander and Porus in this image is strikingly similar to a metal engraving by Alonzo Chappel called Surrender of Porus to the Emperor Alexander (1870).

Figure 4: Chappel, Alonzo, Surrender of Porus to the Emperor Alexander, engraving, 1870, (Johnson Fry & Co. Publishers, New York) http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00routesdata/bce_399_300/alexander/alexander.html.

Notice in the AI-generated image how Alexander is wearing a headband, while Porus is wearing a tiered headdress, matching Chappel’s work. There are few ancient depictions of Alexander and Porus, but most show Alexander riding a horse and Porus riding an elephant with little detail. Because there are few ancient depictions of Hellenistic Central Asia, generative AI is going to draw its information about these ancient people from the modern depictions that are widely available.

Sometimes, details from ancient sources can appear in AI-generated imagery, but they also have risks for potential bias.

Figure 5: OpenAI, DALL-E 3 (8 August 2024 version), personal communication, generated by Edward A. S. Ross on 14 October 2024. Prompt: “Create an image of Euthydemus, the Greco-Bactrian King.”

This image was created by DALL-E 3, OpenAI’s image generation model, from the prompt “Create an image of Euthydemus, the Greco-Bactrian King”. This prompt was inputted into ChatGPT because DALL-E 3 is integrated into the conversational model. ChatGPT that proceeds to generate an image prompt for DALL-E 3 to use as the basis for its image generation. ChatGPT’s generated prompt for DALL-E 3 in this case was:

A detailed image of Euthydemus, the Greco-Bactrian King, depicted as a powerful ruler from the Hellenistic era. He is shown wearing a royal diadem, a symbol of his kingship, and adorned in traditional Hellenistic armor with intricate designs. His expression is regal and commanding, with a strong, mature face and a neatly trimmed beard. He stands in front of a grand palace with Hellenistic and Eastern architectural elements, symbolizing his reign over a multicultural empire. The background includes soldiers and banners, with a mountainous landscape representing the regions he ruled over.

OpenAI, ChatGPT-4o, 8 August 2024 version, generated by Edward A. S. Ross on 14 October 2024.

Euthydemus I (r. c. 224-195 BCE), a Greco-Bactrian king, is presented in the AI-generated image as a “powerful ruler from the Hellenistic era” and is “adorned in traditional Hellenistic armor with intricate designs”. The armour in the image appears quite similar to that which Alexander the Great wears as the first image on the “Wars of Alexander the Great” Wikipedia page.

Figure 6: Alexander detail featured on the “Wars of Alexander the Great” Wikipedia page from the Battle of Issus Mosaic, mosaic, c. 100-120 CE, (Naples National Archaeological Museum, Italy), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_the_Great_mosaic.jpg.

This image depicts a Roman mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii (c. 100-120 CE). Both the leather tassels and embroidered face on Alexander’s armour appear in DALL-E’s Euthydemus image. We must bear in mind that this mosaic is Roman in origin, 400 years after Alexander died. So, its interpretation of Alexander, and in turn Hellenistic armour, is biased towards Roman interpretations of the Macedonian ruler. Since the Alexander image was freely accessible through Wikipedia and was likely one of the first images that appeared in a web search when the training dataset was gathered, it is highly likely that this image, or a similar form of it, was integrated into the model and given a higher weighting due to its relevance factor in the search. Thus, the Roman bias enters AI-generated images of Greco-Bactrian rulers.

One of the major issues for studying Hellenistic Central Asia, as seen above, is the persistent bias towards one cultural origin for its people over another. Generative image AI is zeroing in on these biases, and they appear as key parts of any images generated about these people. For example, this AI-generated image of Aï Khanoum, a Hellenistic city in Bactria, features several columned temple structures, a popular aspect of Classical Greek temple architecture.

Figure 7: OpenAI, DALL-E 3 (8 August 2024 version), personal communication, generated by Edward A. S. Ross on 14 October 2024. Prompt: “A detailed depiction of the ancient city of Ai Khanoum, an ancient Hellenistic city located in what is now northern Afghanistan. The city should be shown with a blend of Greco-Roman architecture and Central Asian elements. The landscape is surrounded by mountains, and the city includes impressive structures like a large gymnasium, Greek-style temples with columns, an amphitheater, and the palace ruins. The scene should feel sunlit, with a warm, arid atmosphere typical of the region. The surrounding area should have greenery along the Oxus River, contrasting with the dry terrain.”

Although many columns did appear in Aï Khanoum’s architecture, they were blended into other forms of building support rather than forming the whole support structure. This AI-generated image may appear reasonably accurate, but it demonstrates a significant bias towards the Classical world, which is present in both the scholarship and our current artistic representations of Aï Khanoum.

Generative image AI outputs are a conglomeration of the available sources fed into its dataset. Because the ancient sources for Hellenistic Central Asia are few and far between, they are vastly outnumbered by modern representations of these ancient people. As such, any AI-generated image is heavily biased towards modern presentations and needs to be properly contextualized before use. We must be aware that this will be the case and critically examine AI-generated content before using them to illustrate discussions of history. Furthermore, as seen above with Euthydemus and Aï Khanoum, some generative image models will automatically add several details about the prompted figure, region, or concept to the image prompt from its dataset. Unless a user is aware of the biases present in generative AI dataset and criticizes the inaccuracies in the created prompt, generative image AI tools will continue to perpetuate these biases. It is crucial that all of us, historians, influencers, and interested people alike, become more digitally literate to be more critical of the content we consume. Otherwise, problematic understandings of history will continue to grow with the sheer magnitude of “History Facts” appearing on social media feeds.

Following from this, generative music tools and generative text tools have further biases that need to be recognized. In parts two and three, we will discuss the major issues that these tools have for presenting Hellenistic Central Asia.

Cover Image: OpenAI, DALL-E 3 (8 August 2024 version), personal communication, generated by Edward A. S. Ross on 15 October 2024. Prompt: “A vivid landscape of Hellenistic Bactria, set in a mountainous region with Greek-style temples and ancient fortresses blending into the rugged terrain. The scene includes a bustling city at the crossroads of Greek and Central Asian cultures, with columns, statues of Greek gods, and people dressed in Greek and Bactrian clothing. In the background, tall mountains rise above the city, and caravans of traders are visible, emphasizing Bactria’s position on the Silk Road. The architecture combines Greek classical elements with local influences, and the atmosphere reflects a blend of Greek and eastern civilizations.”

References

Battle of Issus Mosaic, c. 100-120 CE, Naples National Archaeological Museum, Italy. Accessed October 15, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_the_Great_mosaic.jpg.

Chappel, Alonzo. Surrender of Porus to the Emperor Alexander, 1870, Johnson Fry & Co. Publishers, New York. Accessed October 15, 2024. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00routesdata/bce_399_300/alexander/alexander.html.

Moreland, W. H., Chatterjee, Atul Chandra. “The Greeks in the Punjab (Ancient India).” Historymarg.com, December 23, 2023, https://www.historymarg.com/2023/12/the-greeks-in-punjab-anciant-india.html?m=1.

OpenAI. DALL-E-3 (8 August 2024 version) [Text-to-image model]. 2023. https://openai.com/dall-e-3.

PaginasFuriosas. “”Bessus, el nuevo Gran Rey” Mientras Alejandro avanza hacia Bactria, Bessus se proclama el nuevo Gran Rey. ¿Será él una verdadera amenaza para Alejandro o simplemente otro rival en su camino?” X, September 26, 2024, https://x.com/PaginasFuriosas/status/1839248190387708271.

Shan, Shawn, Ding, Wenxin, Passananti, Josephine, Wu, Stanley, Zheng, Haitao, and Zhao, Ben Y. “Nightshade: Prompt-Specific Poisoning Attacks on Text-to-Image Generative Models.” IEEE Security and Privacy (2024): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.13828.

Wikimedia Foundation. “Wars of Alexander the Great.” Last modified October 8, 2024 at 19:42 (UTC). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wars_of_Alexander_the_Great.

3 thoughts on “Hellenistic Central Asia through the Eyes of GenAI – Part 1: Images”