If you are interested in digital humanities, cultural heritage, or any field that involves working with images and audio/visual materials online, chances are you have come across the acronym IIIF, the International Image Interoperability Framework (https://iiif.io/). This is a set of open standards (e.g., REST, JSON, RDF, etc.) for “delivering high-quality, attributed digital objects online at scale.” This grassroots initiative was launched more than a decade ago to transcend institutional bureaucratic boundaries and facilitate easier access to large, digitised collections. With an ever-growing network of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM) from around the world, IIIF is well on its way to becoming the standardised way for institutions and individuals to share, view and interact with digital images on the Internet.

The problem that IIIF solves

Although many GLAM institutions have been working on digitising their collections for decades, access to these resources is limited to network-specific applications and connected search interfaces (like your library’s OPAC front-end), resulting in the creation of so-called data silos. IIIF’s mission statement is therefore: “Break down silos with open APIs [to give] you and your audience freedom to work across barriers.”1

IIIF aims to provide a common framework for describing and delivering images and audio-visual material available over the internet, as well as structural metadata about image sequences. When institutions that hold digital objects provide IIIF endpoints for their content, any IIIF-compliant viewer or application can be used to display both the images and their metadata. This means that researchers and users can:

- Access and view digital objects from different repositories using a single viewer or application of their choice (allowing easy cross-referencing of materials from different institutions)

- Compare, zoom, rotate, crop, annotate, and share digital objects across repositories

- Search for text or annotations on digital objects

- Publish and reuse digital objects in various formats without vendor lock-in (i.e. democratising access to these collections)

If you want to learn more about the workings and possibilities of IIIF, I can recommend this training site which offers plenty of hands-on examples and exercises.

What IIIF can do for us Digital Orientalists

Let’s begin with a brief excursion into the operation of IIIF. For this, let’s take this map of Tibet from 1981 as an example.

A total of nine individual maps were digitised by the Library of Congress and put together as a composite. While a download of the map is available, it amounts to a hefty 1.3 GB. Anyone who has attempted to manoeuvre an image file of this size on a standard laptop without experiencing stuttering or recurring “circles of death” will know that this is not an easy task. This is where IIIF flexes its muscles. Once the image is uploaded, it is rasterized. A compatible viewer displays only those blocks that are necessary for the operation when zooming and manoeuvring so that even with a limited internet connection and a moderate end device, things work smoothly. IIIF, therefore, provides a sustainable way of putting image resources online.

The power of annotations

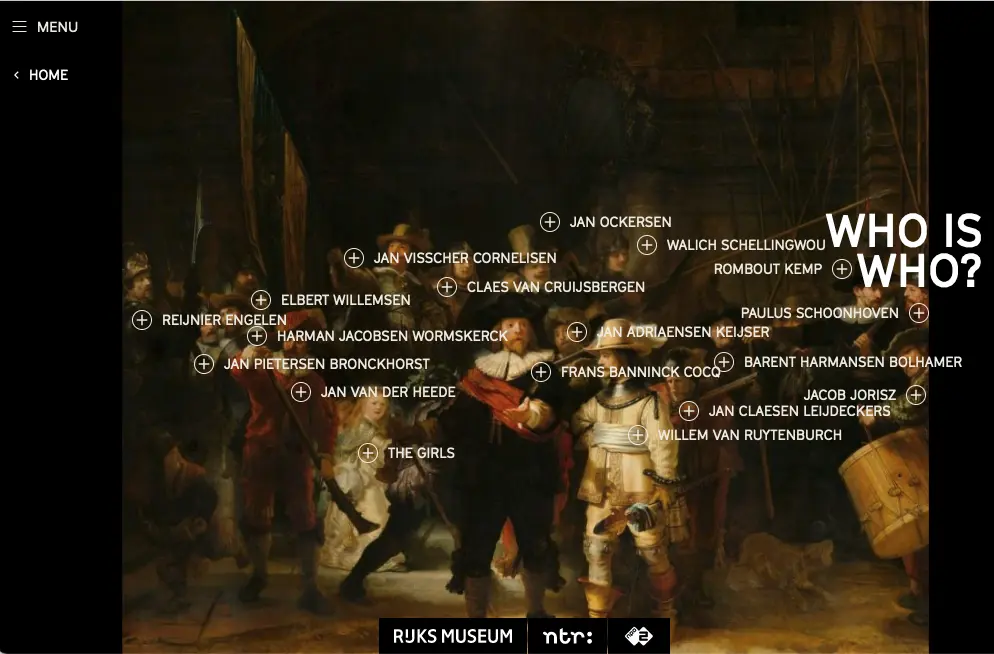

Over this “canvas” grid, which consists of coordinates, you can overlay a number of exciting extensions such as annotations. These can be in the form of shapes, comments, or links (to other resources such as images or possibly other IIIF canvases) and are bound to specific coordinates so that they maintain their position when zoomed in.

As researchers, we are not only obliged to use public funds to conduct the best possible research but also to communicate our research findings in accessible ways. Annotation-based exhibition IIIF extensions, such as Storiiies or Exhibit provide opportunities to bridge storytelling with research and create interactive learning materials. Users can explore historical documents or artworks in fascinating ways. At this point, I invite you all to take a short digital tour through a selection of royal wallpapers from the Qing dynasty or Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights”. For teachers, this opens up new avenues to engage their students with learning materials and objects in an interactive way, and GLAM institutions can enhance their collections with metadata and context online.

If you are already sold at this point and want to start creating your own interactive adventure right away, hop over to the British Library’s Digital scholarship blog for a simple how-to guide and visit Biblissima for thousands of IIIF-compliant links, called manifests, from the collections of participating institutions.

Annotations as research outputs: the future of IIIF?

In addition to its fun interactive capabilities, the IIIF framework also has the potential to transform the way we produce research articles and monographs in the future. A little while ago, I caught up on the latest digital humanities research and trends during the DHOxSS summer school at the University of Oxford. Among the many speakers was Neil Jefferies, Head of Innovation at the Bodleian Libraries, and a longstanding advocate of the IIIF initiative. In our workshop strand, he presented not only the technological nuances of the IIIF protocol but also gave us insights into the range of available extensions and concluded with a look behind the scenes of future developments.

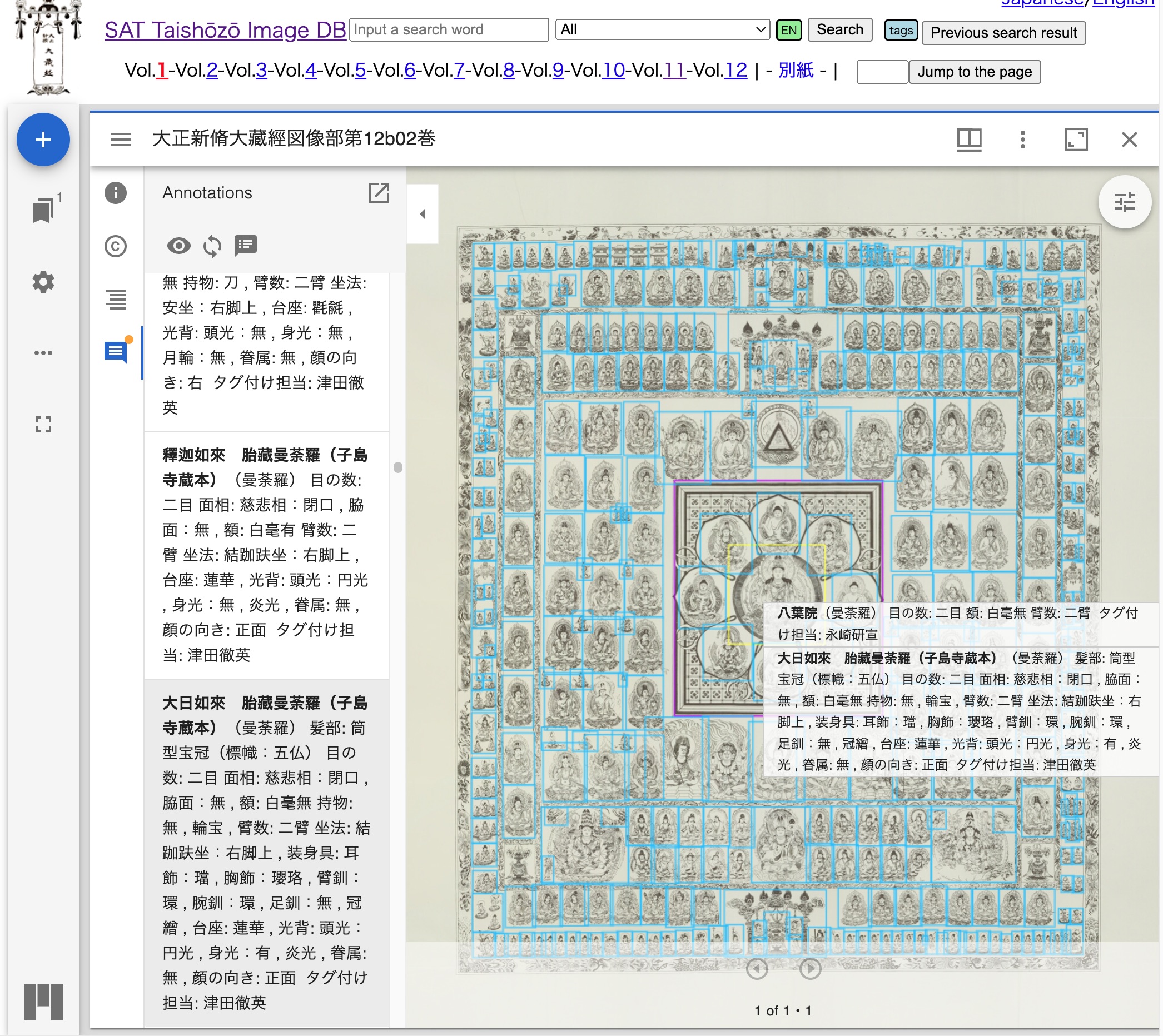

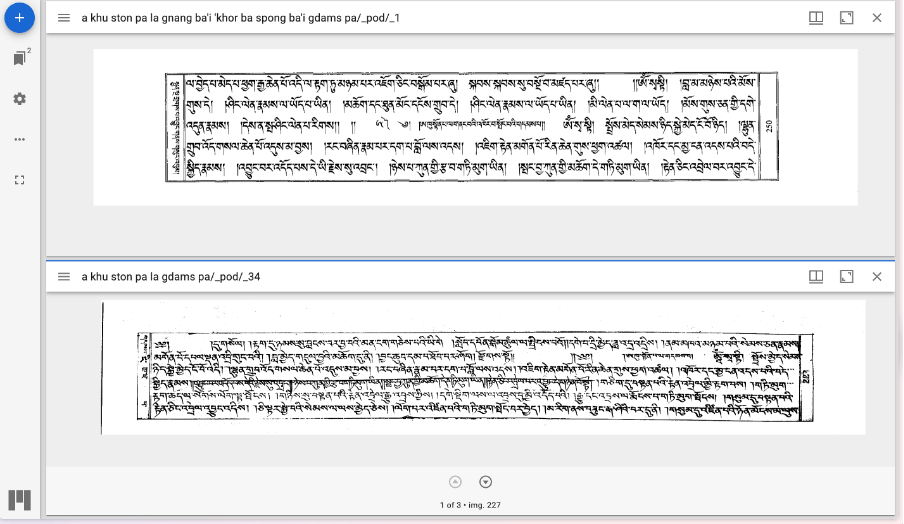

I am a historian of Tibetan and Mongolian history and completed my BA and MA under the guidance of two traditionally trained philologists. Critical editions and meticulous translations of textual sources were imparted to me as the standard of (German) philological work. Consequently, it entailed searching the archives for manuscripts, describing, and transliterating them, noting any physical peculiarities, and providing the provenance of the artefact along with background information on the author, if available. Due to institutional word and methodological limits, dissertations were written in this fashion, and much like the digital collections of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums once operated in their data silos, research results were produced for only a small, initiated group of scholars. But what if we could outsource this undoubtedly important research step and allow more space for analysis, contextualisation, and comparative perspectives? Instead of pages of text, this could be distilled into one hyperlink. You can find an illustration of this process on the website of the Old Tibetan Documents Online, which has embedded an IIIF manifest and links pointing to the annotations in rectangular boxes.

The days of long appendices and footnotes packed with transliterations (in Times New Roman 10 point) could be numbered! Equally, the readership of studies wanting to have a quick look at the original material themselves could also stand to benefit since no tedious search for the primary sources used would be necessary, but only one click away.

In addition, linking annotations across multiple IIIF canvases can significantly expand the functionality and scope of editions. Not only can multiple manifests be loaded side by side into the viewer, but multiple analyses by different researchers on a given text can coexist and be easily compared, contrasted, and linked. Annotations can also be applied to more than one target. This allows for approaches that span multiple witnesses or versions of the same document, but also across disparate documents, to map the development of an idea, theme, or idiom, for example.

Still, there are a few challenges that need addressing first. As Neil Jefferies informed me, a first field test will soon be launched in cooperation with the open-repository service Zenodo hoping to find solutions to these issues:

- Authors of annotations (read translation, transliteration, contextualisation, description, and metadata) should not only be acknowledged as authors, but their work should be recognised as valid scientific outputs. One solution might be to sign in via one’s unique Open Researcher and Contributor ID, ORCiD for short, which would then automatically register the annotations as a scholarly work.

- Version control: If we want to treat annotations as part of ongoing intellectual discourses in the future, it is worthwhile to document any changes and revisions with version numbers and thereby also guarantee cite-ability. As of today, a DOI is already automatically generated when a file or data set is uploaded to Zenodo, which may then be expanded to include version numbers. The granularity & layering of annotations is then up to each researcher.

- Future research needed: IIIF and the power of annotation do have enormous potential to transform the humanities, but it only works if you have images of the source material. For completeness, you need to be able to do standoff annotation on pure text – and across texts and images. This remains a topic for future research.

Conclusion

IIIF is a powerful and promising framework that can transform the way we access, use, and share digital objects online. Whether you are a researcher, a user, or an institution, IIIF can offer many benefits and opportunities.

It can facilitate access to cultural heritage and opens up solutions for digital storytelling and linking scientific research results to their (digital) provenance. When these collections are enriched with further metadata and linked to other resources, we can reconnect isolated cultural artefacts and integrate them into an ever-growing information network. As we move forward in this digital age, IIIF can become a testament to the power of open standards in shaping the future of technology and human knowledge.

3 thoughts on “Transforming the way we interact with digital (text) collections with IIIF”