Museums and collections of Islamic art around the world have dedicated a substantial part of their efforts and fundings to digitizing and making their collections more accessible. This trend is evident through the growing availability of open-access and online collections, both from public and private institutions. While this shift enables the general public to access and appreciate artworks from remote locations, it also presents a wealth of data for researchers to explore.

In addition to high-quality digital images of the objects, many major public museums now publish related catalogue entries online. These entries provide detailed information about various aspects of a given artifact. However, different museums follow varying standards and architectures in presenting this information, typically in raw metadata format according to their respective institutional norms.

From a general perspective, this data may be viewed as mere descriptions of museum objects, much like the informational cards typically installed beneath artworks displayed in permanent or temporary museum exhibitions. However, for architectural historians, this data has the potential to serve as a treasure trove of information, offering valuable insights into the hidden stories these objects can narrate.

What sits in Islamic art museums and collections varies in type; ranging from ceramics, glass, metalware, ivory, textiles, carpets, miniature paintings, and manuscripts to pieces of historical buildings that have been acquired through different means. Among these, architectural fragments are particularly intriguing, as they serve as tangible evidence of destruction and displacement. Essentially, when we encounter an architectural element in a museum, it implies that the piece was removed from a standing or ruined building and somehow ended up on display in a museum, a context it wasn’t originally intended for.

Contemplating the journey of an architectural element from its original location to its current setting, especially in the case of Islamic architectural elements, sheds light on the colonial mindset of European and later North American collectors of Islamic art. Nevertheless, the documentation and presentation of such objects within the museum context, whether physically or online, rarely address this hidden aspect.

With the ongoing and growing discussions on cultural restitution and calls for critical re-examination of museum collections, the imperative to make sense of these holdings, both individually and collectively, has grown. Simultaneously, advances in data management and representation platforms have opened up new avenues for historians to conduct comprehensive analyses of available data.

In this piece, I aim to explore the innovative Arches platform and highlight its potential for imbuing museum repositories with fresh interpretations. Currently, I am employing Arches in a project focused on recontextualizing Persian architectural fragments, accessible as digital documents on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art website.

The Arches Platform is a powerful open-source data management tool designed for the purpose of handling cultural heritage data. It provides a comprehensive framework that enables organizations, museums, and heritage professionals to document with precision and efficiency. Arches’s flexible design allows users to adapt any type of data model and that allows it to be used in documenting various types of heritage resources, from archaeological sites and historic buildings to artworks and even intangible cultural practices. Its user-friendly interface and powerful search capabilities facilitate new queries and analysis of the stored information, as well as creating new narratives.

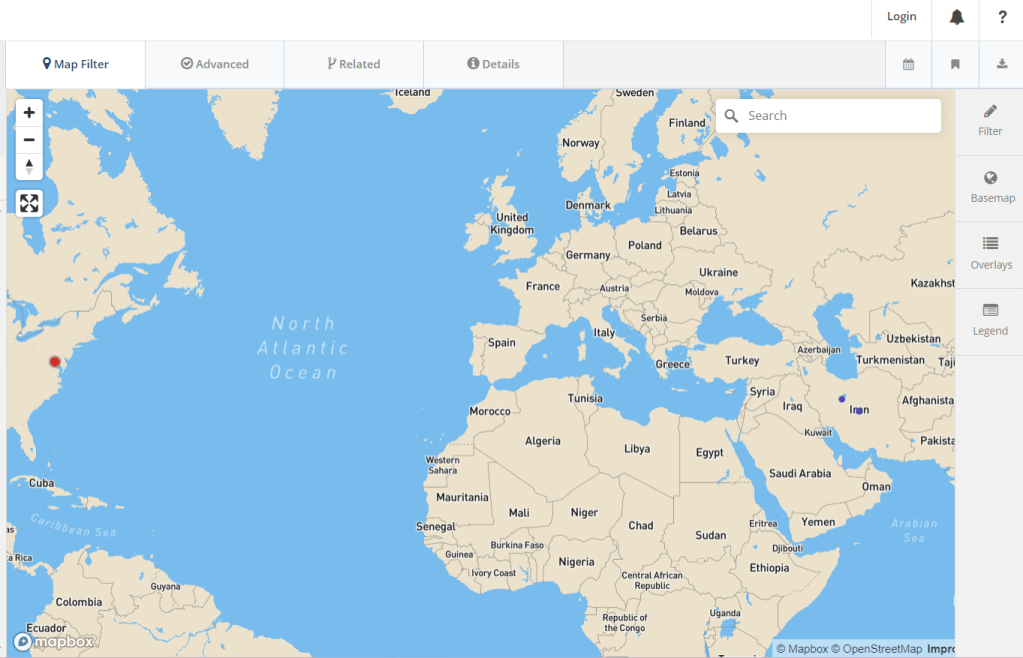

Arches developers categorize its features into two main groups: “Data Management” and “Data Discovery & Visualization” (figure 1). Managing data with Arches includes collecting and storing data with data structures that are either developed from scratch, or implementing existing standard data structures. The power of data visualization with Arches lies in its spatio-temporal construct, which proves particularly advantageous when working with architectural materials. Each data point in Arches can be linked to its spatial and temporal data, and these two aspects can be defined when making queries.

Here, I will briefly outline the process through which museum online catalogues can be redefined using Arches by using examples from Persian architectural elements in the Smithsonian’s collection. A keyword search for “Iran” on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art online collection, specifically under the category of “architectural elements” (at the time of writing this post), retrieves 497 digitized objects.

Each piece is accompanied by a digitized catalogue or metadata, including formal descriptions (such as dimensions, color, decoration), known origins, provenance, exhibition history, and current location, among other details. Aiming to connect each piece with its original location, we can utilize Arches to reinterpret the objects as a collection, uncovering new connections based on documented information about each piece, while also identifying unknowns and fields that require further investigation.

For instance, a tile with accession number F1973.16 is documented in the collection as belonging to the Ilkhanid era from Sultanabad (Iran). The documentation notes that the piece was acquired in Iran by Myron Bement Smith and was subsequently gifted to the museum by Mrs. Myron Bement Smith. Through Arches data collection, we can capture this information using controlled vocabularies (like the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus) and establish conceptual connections between different aspects of this particular object, based on Reference Models (such as the CIDOC-CRM ontology).

The end result is viewable on the Arches built-in map, with customizable visualization options. Enhancing this map with multiple data points will, at its most basic level, provide a list of objects bound by times and locations. On another level, it will display relationships between events, persons, and methods of transfer for these objects. This yields a multi-layered map derived from museum collections, revealing how objects came to be in specific locations, who the involved agents were, and the actions that contributed to their displacement. Hopefully, this will pave the way for making assumptions about the missing links between objects in museums and the buildings they were originally part of.

In short, the integration of the Arches platform represents a significant advancement in the study of museum artifacts, particularly exemplified in the re-examination of Persian architectural fragments. This innovative tool not only facilitates precise and efficient documentation of cultural heritage data but also empowers researchers and institutions to unravel hidden narratives behind objects. By bridging the gap between spatial and temporal dimensions, Arches enables a comprehensive understanding of the journey each artifact undertakes, shedding light on its origins and pathways to museum display. As discussions on cultural restitution and critical assessments of museum collections continue to evolve, Arches stands as a pivotal resource, offering new avenues for meaningful interpretation and contextualization. In essence, Arches can be used as a highly customizable tool among architectural historians in examining and analyzing museum materials as a rich yet overlooked source of information.

One thought on “Uncovering Hidden Histories of Artifacts with Arches Platform: A Case Study of Persian Architectural Fragments”