The rise of digital humanities has revolutionized scholarly pursuits, particularly in literature, where the accessibility of digital images of manuscripts from private collections holds immense significance. While public archives house valuable manuscripts, many treasures remain hidden in private holdings. The integration of digital tools and the digitization of these private collections offer unprecedented opportunities to understand established literary works better. This article explores how access to digital images from private collections enhances textual analysis, illuminates the evolution of literary editions, and unveils obscured facets of known literary legacies, marking a transformative era in scholarly exploration at the intersection of technology and the humanities.

Introduction:

The Chahar Maqala (Four Discourses) is a well-known, Persian literary work in Mirror for Princes genre, composed by Ahmad bin ‘Umar bin ‘Ali known as Nizami ‘Aruzi Samarqandi (fl. 1110-1161) around 550AH/1155. It discusses court professions essential for a prince: secretary, poet, astrologer, and physician.

The text was first edited by Muhammad Qazvini and published in Cairo in 1327AH/1909 CE. Qazvini’s edition was mainly based on three manuscripts, among them was the oldest known copy of the Chahar Maqala, dated 835/1431, which was produced for the library of the Timurid Prince Baysunghur (1397-1435) in Herat. Qazvini only had access to a copy of Baysunghur’s manuscript made for Edward Browne when the manuscript was preserved in ‘Ashir Efendi Library (MS 285),[1] now known as the Turkish and Islamic Art Museum, MS 1954.[2] The Chahar Maqala, was then transferred to the Islamic Foundations Museum at its inauguration in 1914, whose name was changed to Turkish and Islamic Art Museum (TIEM) in 1923 (MS 1454).[3]

Qazvini found the Baysunghuri copy’s text accurate and precise, with a plethora of significant variants compared with other copies. Prince Baysunghur’s manuscript, written in nastaʿliq with seventeen lines to a page, in 51 folios of 225 x 152 mm, includes nine illustrations. The scribe’s name is scratched out but his sobriquet, al-Sultani, remains intact. There have been attributions to Shams al-Din Haravi in previous studies, but such assumption should be dismissed, because Shams received the princely epithet in 831/1428, and signed Shams al-Baysunghuri ever since, namely in the Humay and Humayun of Khwaju Kirmani, dated 1428 (Vienna, Austrian National Library, Cod. N.F. 382), and the Kalila u Dimna, dated 1430 (Istanbul, Topkapi Palace Library, R. 1022).

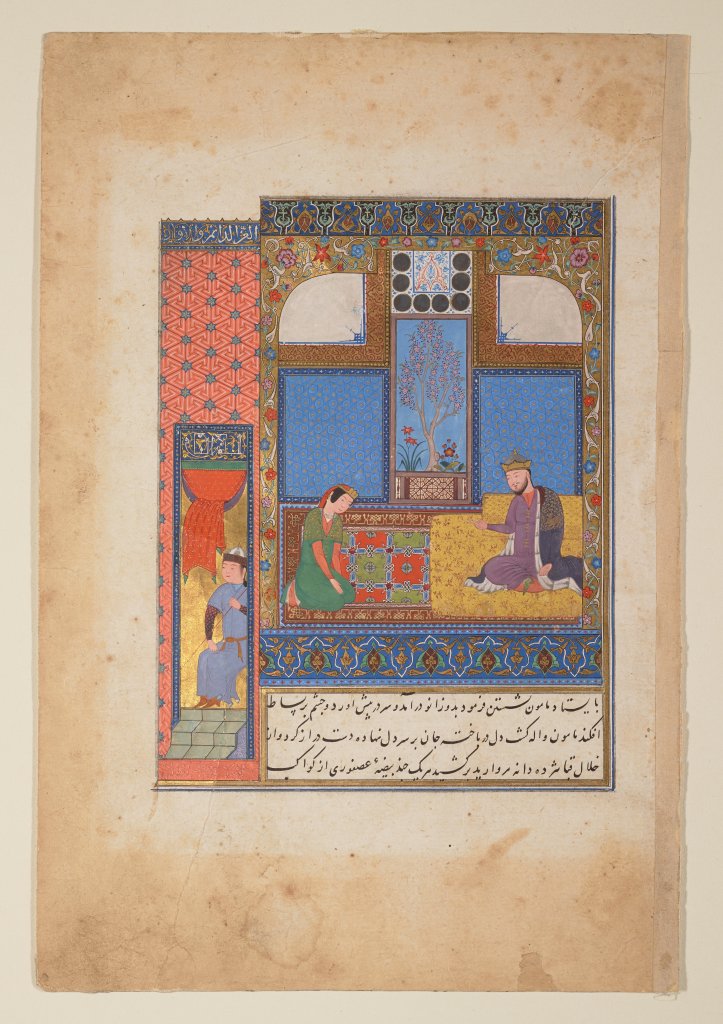

When Mojtaba Minovi examined the manuscript in Istanbul in 1956, he identified the codex had suffered from two lacunae: one between folios 15 and 16 with the missing folios containing an illustration of the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun (786–883) proposing marriage to Fazl’s daughter, now at Minneapolis Institute of Art, accession no. 51.37.30 (fig. 1). [4] The text in the Minneapolis dispersed folio is the continuation of the text in the TIEM manuscript which confirms Minovi’s identification. The second lacuna appears between folios 27 and 28. Eleanor Sims, who discusses the manuscript and its lacunae in her 1976 article, believes that the second one lacks six folios with at least one illustration.[5] Minovi deduced the number of folia lost at this part as four and Qazvini as ten.

The terminus ante quem for dismemberment of the manuscript is 1914, when the Islamic Foundation Museum officially registered and stamped manuscripts with its seal impression and their accession number. All illustrated folios within the Baysunghuri codex are also marked that way; however, the Minneapolis folio lacks the seal impression, which indicates it was carved out of the manuscript before 1914. It is noteworthy that the dismemberment of the Baysunghuri Rasāyil (Bernard Berenson Collection, Florence) which is now scattered in four collections across the world (Sacker Gallery of Art, Chester Beatty Library, Berenson Collection, and Malek Library and Museum) also happened prior to its purchase in 1910.

Fig. 1) Al-Ma’mun Proposes Marriage, Chahar Maqala, Minneapolis Institute of Art, accession no. 51.37.30.

The Newly Emerged ‘Oldest Copy’

It was long believed that the Baysunghuri Chahar Maqala at the TIEM, dated 835/1431 was the oldest extant manuscript of the text and the first and sole copy ever illustrated. However, the emergence of a Jalayirid copy on the market in 2017 changed that belief. It was sold in London Christie’s auction on 26 October 2017 for over £93,000.

It presents an example of nastaʿliq script in its formation years, in the hand of ‘Awad bin Muhammad bin Ardashir, in Tabriz or Baghdad, and is completed beginning of Sha‘ban 785/September-October 1383. It marks a year after Sultan Ahmad Jalayir (r. 784-813/1382-1410) came into power. The Jalayirid copy contains 49 folios of 247 x 160 mm with nineteen lines to a page.

Sultan Ahmad Jalayir was a great patron of the arts and music, who ruled Tabriz and Baghdad, but got involved in a series of political conflicts, starting with Timur’s attack in 1384 and ending with his defeat and demise by Qara Yusuf in 1410. His court scribes, artists, musicians, scientists, and scholars were distributed in the courts of Timurid princes.

Prince Baysunghur probably inherited the majority of manuscripts and artists from Sultan Ahmad’s court when established his library-atelier in Herat by 1420. The artists continued to practise the Jalayirid style in Baysunghur’s productions. There is evidence of the prince ordering his artists to create manuscripts in the manner of Sultan Ahmad’s, in the same format, size, and style.[6]

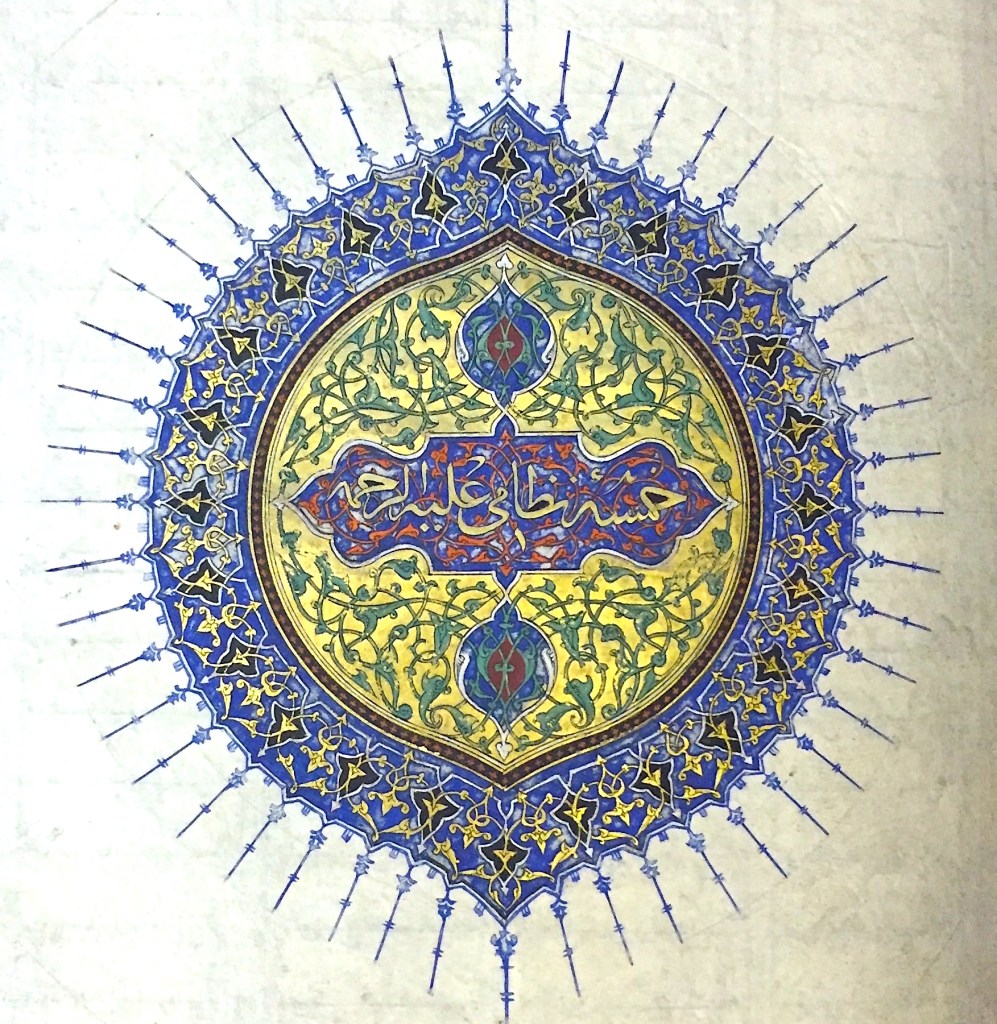

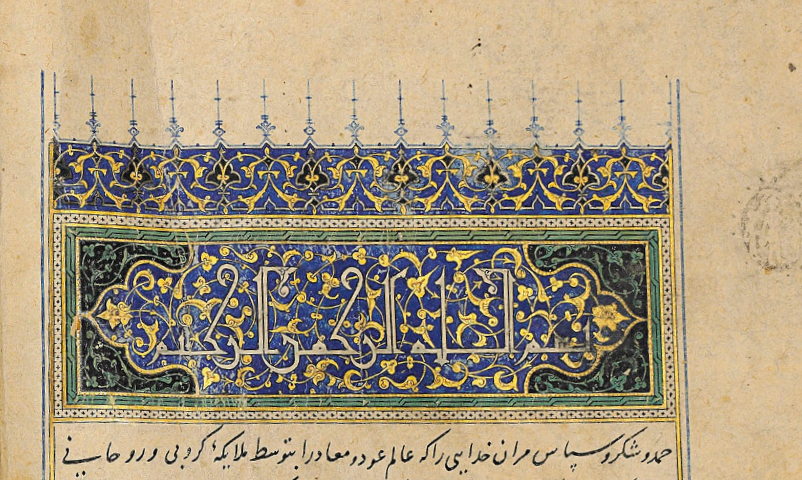

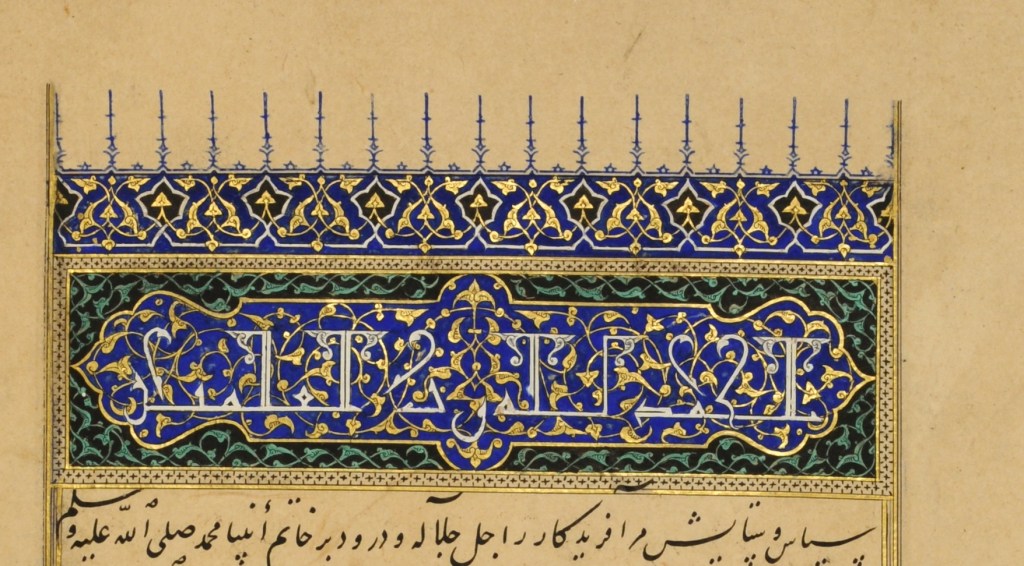

The Christie’s catalogue provides an accurate and concise description of the Jalayirid copy.[7] It opens with an illuminated shamsa (medallion) bearing the title Majma’ al-Nawadir (The Compilation of Rarities), which was the original title of the Chahar Maqala. This illuminated shamsa was used as a model at Baysunghur’s library in a few other manuscripts, such as the Khamsa of Nizami, dated 833/1430 in the Malek National Library and Museum (fig. 2).

Fig. 2) Left: Chahar Maqala, dated 785/1383, Private Collection. Right: Khamsa of Nizami, dated 833/1430, Malek National Library and Museum, Tehran (MS. 6031).

Our limited knowledge about the manuscript sold in Christie’s reveals that two illustrations correspond to those in the Timurid copy. Digital images of the entire manuscript, however, will provide us with the subject intended to be illustrated from the break-lines relevant to each blank blocks in the text.

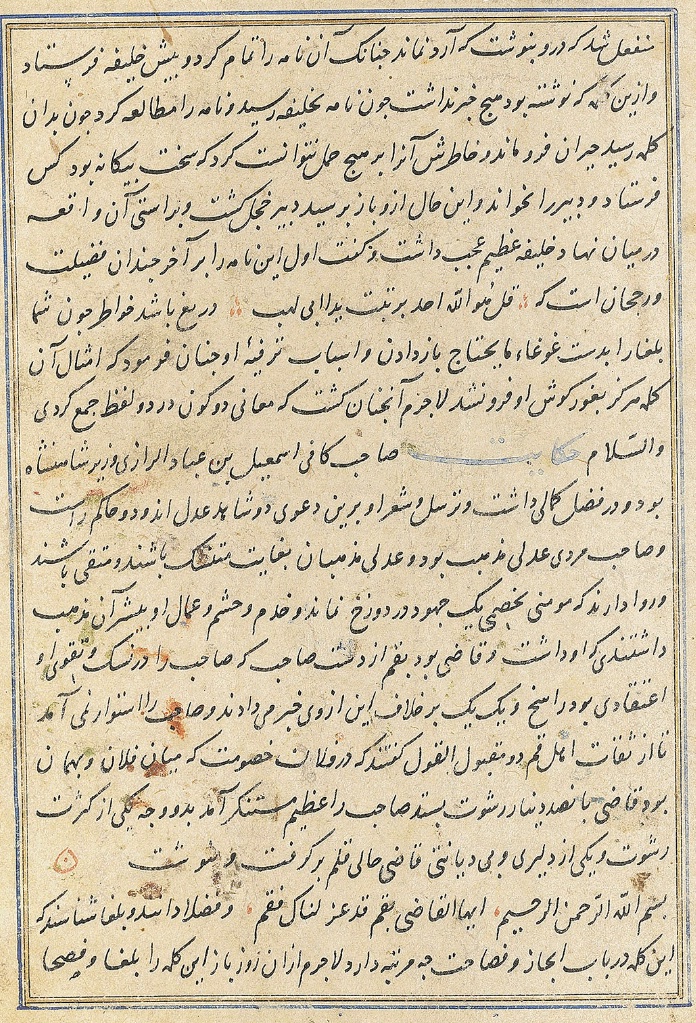

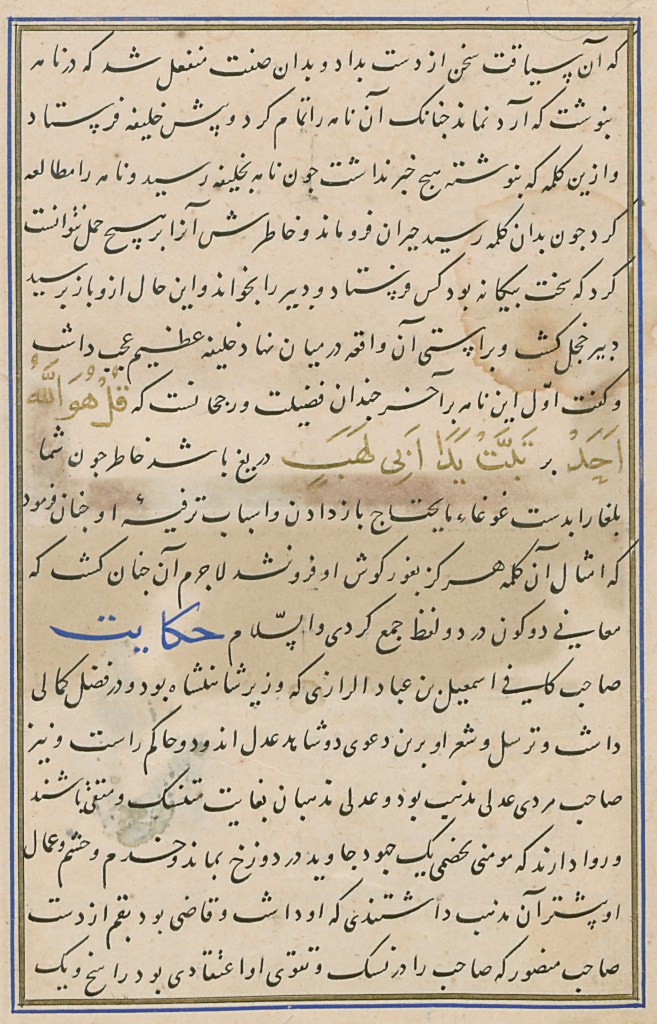

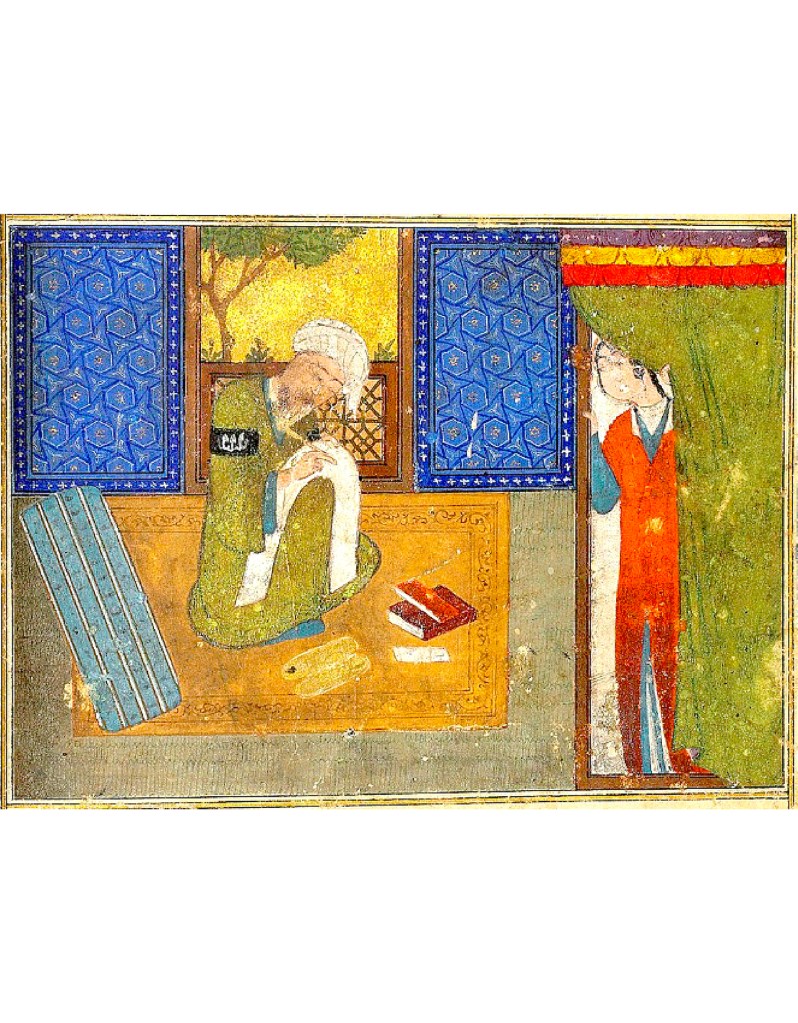

A textual comparison between the Timurid copy and the limited images of the Jalayirid manuscript available in Christie’s Catalogue reveals that the descendent copy was transcribed from the forerunner Jalayirid text of the Chahar Maqala, which means the Jalayirid copy was possessed by the Timurid Prince Baysunghur (fig. 3). The pictorial elements in the illustrations were explicitly a source of inspiration for the artists in Herat workshop (fig. 4), although the quality of the Jalayirid painting is clearly superior.

Fig. 3) Text comparison between the Jalayirid and Timurid manuscripts. The Jalayirid text (left) vs Timurid text (right)

Unfolding the Jalayirid copy of the Chahar Maqala of Nizami ‘Aruzi rectified the false belief that Baysunghur’s manuscript at TIEM was the oldest surviving copy. This raises the necessity of a revised edition of the text, based on the Jalayirid manuscript, which is in fact the oldest copy of that literary text.

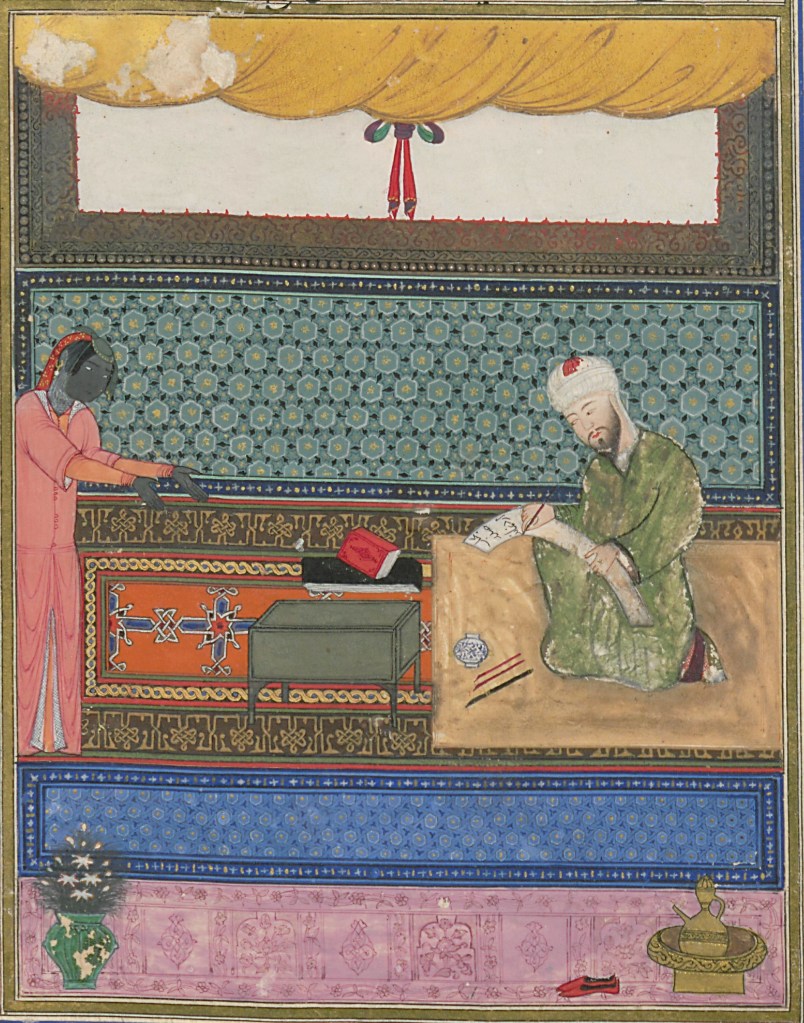

Fig. 4) The Secretary of the ‘Abbasid Caliph Disturbed by His Maidservant. Jalayirid Chahar Maqala (left), Baysunghur’s Chahar Maqala (right)

The opening shamsa in the Jalayirid copy is followed by an elegantly illuminated heading, the like of which are found in several Baysunghuri manuscripts (fig. 5). This copy contains three illustrations, three incomplete paintings and nine spaces left blank for more paintings. The six complete and incomplete scenes in this manuscript include:

The illustrated scenes in the Baysunghuri copy are listed in Eleanor Sims’ article as below.

1) The Secretary of the ‘Abbasid Caliph Disturbed by His Maidservant (fol. 12v)

2) The Caliph Ma’mun Marries the Daughter of the Barmakid Vizier (Minneapolis Institute of Arts)

3) The Caravan of Abu Riza b. ‘Abd al-Salam Encounters the Nasnās in Turkestan (fol. 6v) (Sims, fig. 1).

4) The Secretary of Bughra Khan Answers the Query of the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud Yamin al-Daula (fol. 17r) (Sims, fig. 4).

5) Rudaki persuades the Samanid Amir Nasr b. Ahmad to Return to Bukhara After Four Years’ Absence in Herat (fol. 22r) (Sims, fig. 5)

6) Sultan Mahmud Commands the Turkish Youth Ayaz to Cut His Hair So the Sultan May Escape the Temptation of the Youth’s Beauty (fol. 23v) (Sims, fig. 6).

7) The Poet Farrukhi Recites His Qasida on the Branding-Ground for the Amir Abu al-Muzaffar (fol. 27r) (Sims, fig. 7).

8) Ibn Sina Treats the Young Relative of Qabus b. Wushmgir for Lovesickness (fol. 43r) (Sims, fig. 8).

9) The Physician of the Buyid ‘Adud al-Daula Devises Treatment for the Porter (fol. 45r) (Sims, fig. 9).

10) Nizami ‘Aruzi Treats the Daughter of His Host in Herat (fol. 49v) (Sims, fig. 10).

Fig. 5) Illuminated heading. Jalayirid manuscript (left) vs Timurid manuscript (right)

Judging by the subjects, it appears that only two or three images in the Baysunghur’s copy correspond to those in the Jalayirid peer, one of which has long been separated from the TIEM manuscript.

A digital approach to the study of the two codices will come immensely illuminating in at least three categories.

- A careful comparison of the texts will uncover all the variants and emendations that took place at the library of the Timurid prince. I have discussed elsewhere that Baysunghur’s library was not merely a transcribing hub, but they were purposefully editing texts on explicit commands of the prince. This will help enrich previous study on the Timurid editing criteria.

- Now that we know the Baysunghuri manuscript was almost certainly copied from the Jalayirid manuscript, there would be a possibility to precisely calculate the missing folios in each lacuna and settle that issue once and for all.

- Digital images will help us understand the number of illustrations in the Timurid manuscript which were copied or inspired from the Preceding Jalayirid copy. The pictorial elements, compositions, layout, break-lines before each painting, the choice of subject, and rendering style.

Gleaning such significant information can only happen if manuscript owners and collectors agree to contribute to scholarly works on their treasures by sharing digital copies of their object. This will not only increase the value of their objects, but it will also help a successful research and knowledge on certain disciplines, in our case Persian literature, and art history.

[1] See Browne, Edward G. “The Chahár Maqála (“Four Discourses”) of Ni̲d̲hámí-i-‘Arúḍí-i-Samarqandí”, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (July 1899): pp. 613-663.

[2] Qazvini also used two manuscripts from the British Museum, Or. 3507 dated 1017AH (1608-9) and Or. 2955 dated 1274AH (1857-8). There is also a copy of the Chahar Maqala at the British Library, dated 1279AH (Or. 10982).

[3] https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/tiem

[4] Sims, Eleanor G. “Prince Baysunghur’s Chahar Maqaleh”, in Sanat Tarihi Yıllığı, no: 6, Istanbul, 1976: 376.

[5] ibid: 405-9

[6] For example, in the Preface to Bahram Mirza’s album (see Thackston, Wheeler, M. Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters (Leiden, Boston, Cologne, 2001): 4-18) and in the Jung-i Marathi (Book od Elegies), dated 837/1435, in Tabriz National Library, MS 2967.

[7] Plumbly, Sara. “A Rare Jalayirid Illustrated Manuscript”, Christie’s auction 14218, Lot 8 (26 Oct 2017)

* I am grateful to Mr. Amir Arghavan for bringing this manuscript to my attention, and also for sharing his Persian article. Arghavan, Amir. “Mu’arrifī-i kuhan-tarīn nuskha-yi Chahar Maqala-yi Nizāmī ‘Arūżī, kitābat-i qarn-i hashtum-i hijrī”, Gozareshe Miras, no. 98-99, forthcoming.