In the first post of this series, I introduced the notion of formularity in oral poetry along with a new linguistic approach that treats formulas as constructions of ordinary language. In this piece, I will illustrate a new methodology for extracting formulas from Sanskrit texts, which is based on such a constructionist approach. To illustrate the methodology, I will demonstrate how, thanks to morphosyntactic and semantic information contained in two linguistic resources for Sanskrit, it is possible to extract the basic formula KILL THE DRAGON from the Rigveda (RV). The methodology is applicable to other texts as well as to other traditions, as long as similar linguistic resources are available.

The Vedic Treebank

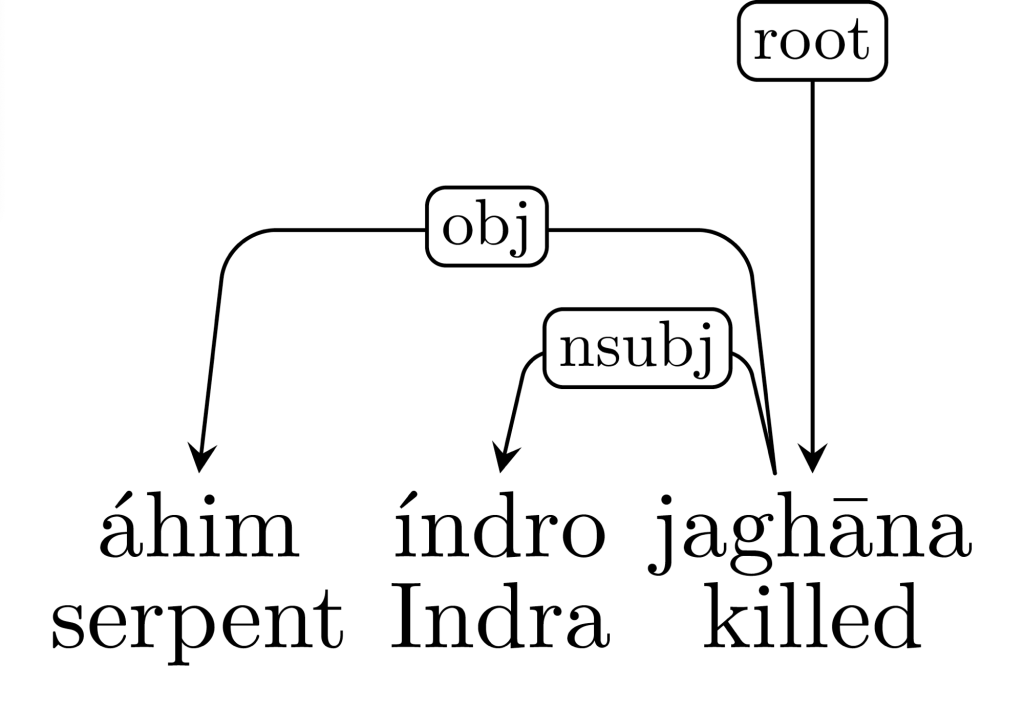

In my second post on The Digital Orientalist, I described what a treebank is and its usefulness in linguistic research to introduce a new project aimed at creating a parallel treebank of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speeches in various Indian languages. The Vedic Treebank (Hellwig et al. 2020) contains selected passages from texts of Vedic literature, syntactically annotated according to the Universal Dependencies (UD) standard. The treebank is hosted within the Digital Corpus of Sanskrit (Hellwig 2010-2024), which resolves sandhi (i.e., sound changes that occur at word boundaries, as in píbendra for píba indra ‘drink, Indra!’) and provides morphosyntactic annotations alongside the raw source texts. Like the Modi Treebank, the Vedic Treebank follows Dependency Grammar and, more specifically, the Universal Dependencies annotation scheme, which has become a de facto standard in this field. Figure 1 contains a dependency tree for the sentence áhim índro jaghāna ‘Indra slew the serpent’ (RV 2.15.1d).

Figure 1. Dependency tree for RV 2.15.1d

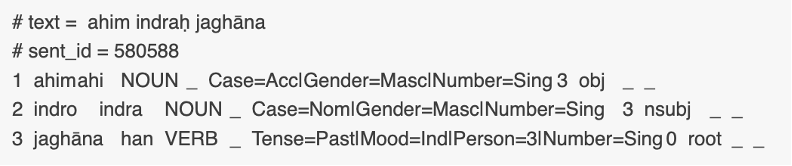

Annotated data is stored in a format called CoNLL-U. It is a vertical, table-like format (i.e., not XML), in which sentences consist of one or more word lines, and word lines contain 10 field storing information on tokens, lemmas, parts-of-speech, morphological features, and dependency relations, plus a “miscellaneous” field which can include any other type of information. Figure 2 shows the annotation of RV 2.15.1d as stored in a CoNLL-U file.

Figure 2. Annotation of RV 2.15.1d in the CoNLL-U format

Although the UD guidelines cover most phenomena found in Vedic texts, some constructions required special attention during the annotation process as they are not attested in the modern languages on which the schema was modeled (for a detailed discussion, see Hellwig et al. 2020). In this context, it is worth mentioning the annotation of compounds, which necessitated a deviation from the UD standard.

Following a lexicalist approach, the UD guidelines attribute the formation of compounds to morphology and recommend not splitting compounds into their elements. However, post-Rigvedic Sanskrit compounds exhibit linguistically infrequent characteristics (such as high recursion or anaphora with elements external to the compound) that can be explained by attributing their formation to syntax rather than morphology. In the context of syntactic annotation, this has led the developers to split compounds into their elements and link them through the same dependency relations (deprel) that occur between independent words. As we will see below, the division of compounds into their parts will prove advantageous in the combined use of the Vedic Treebank and Sanskrit WordNet, as it will allow access to syntactic and semantic properties not only of the compounds as a whole but also of their elements.

The Sanskrit WordNet

I have extensively described the Sanskrit WordNet, the information it contains, its architecture, and its purposes here. For the purpose of this post, it will suffice to say that WordNets are relational databases created to explore the lexicon of a language. Within these databases, word networks consist of nodes for nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, which are assigned to as many synsets as there are meanings associated with them. Synsets (synonym sets) are groups of synonyms accompanied by brief definitions and an identifying ID number. Different lemmas can share one or more synsets, meaning they are (partially) synonymous (Miller et al. 1990, p. 241). The first WordNet was developed for English at Princeton University, and since its creation, various WordNets have been developed for languages around the world.

The construction of the Sanskrit WordNet is one of the objectives of the “Linked WordNets for Ancient Indo-European Languages” project, which is dedicated to creating analogous resources for Ancient Greek and Latin. The Sanskrit WordNet builds on original work by Oliver Hellwig (2017) and inherits the architecture of the original Princeton WordNet, introducing several important innovations (which are described in full in the dedicated post).

Combining the morphosyntactic and semantic annotation for the study of Rigvedic formulas

A case study on the formulaic network KILL THE SERPENT

The idea of combining the Vedic Treebank and the Sanskrit WordNet to extract and analyze formulas from texts stems from the following reasoning: if we consider formulas, just like constructions in everyday language, as recurring pairings of a specific form with a specific function, we can combine the morphosyntactic information contained in the Vedic Treebank with the semantic information in the WordNet to identify previously undetected formulas or to obtain more information about known formulas—whether they are fixed or schematic, what their semantics are, and what morphosyntactic modifications they can undergo. In fact, we can consider some of the information contained in these two resources (tokens, lemmas, morphological features) as proxies for the form of a formula, and other information (syntactic function, lexical meaning of words, and the semantic relations they have with other words) as a proxy for its function. Let us now see how we can apply this methodology to the formula KILL THE SERPENT.

Many cultures around the world attest to one or more myths about a god or hero who slays a dragon or another reptilian adversary, usually simply referred to as a ‘serpent’ (Watkins 1995, p. 297). Benveniste and Renou (1934) reconstructed the Indo-Iranian version of this myth, highlighting the regularities in the phraseology used to narrate it. However, it is Watkins (1995) who is credited with reconstructing a Proto-Indo-European base formula centered on the verbal root *gu̯hen ‘to kill’, which encapsulates the myth itself and is reflected in the various daughter languages. This formula can be schematized as follows (p. 302):

| HERO | SLAY (*gu̯hen) | SERPENT | WITH WEAPON |

| WITH COMPANION |

Let’s now see how this formula is realized in the hymns of the RV. In this tradition, the expressions áhann áhim [1-4] ‘(he) killed the serpent’ and áhann áhim [1-4] ‘(you) killed the serpent’ both refer to the mythical slaying of the demon Vr̥tra by the god Indra, but they differ in terms of person: the first refers to the god in the third person, while the second addresses him directly in the second person. The expressions áhann áhim [1-4] ‘(you) killed the serpent’ and áhann áhim [5-7] ‘id.’, though apparently identical, differ in their metrical position, with the first occurring in syllables 1-4 of the verse and the second in syllables 5-8. Considering semantic, lexical, and morphosyntactic aspects, while setting aside metrical ones, we might identify a formula áhann áhim underlying the three variants. Alternatively, we could forgo morphological restrictions and identify a formula √han- áhim ‘to kill the serpent’ underlying all forms containing áhim as the direct object of a form of the root √han–. Examples (1) to (3) contain some of the formulaic variants identified by Watkins (1995, pp. 304-309):

(1) yo hatvā́ áhim …

REL.NOM kill.GER serpent.ACC

‘He who, having killed the serpent …’ (RV 2.12.3a)

(2) áhaye hántavā

serpent.DAT kill.INF

‘To kill / for the killing of the serpent.’ (RV 5.31.4d)

(3) áhim índro jaghā́na

serpent.ACC Indra.NOM kill.PF.3SG

‘Indra killed the serpent.’ (RV 2.15.1d)

The expression also appears with nominal forms of the verb √han–, such as present participles (ghnánn in 5.31.7b), perfects (jaghanvā́n in 4.17.1c), and desideratives (jíghāṁsataḥ in 1.80.13c). Finally, the verbal phrase expressing the myth of the serpent slaying is sometimes encapsulated in compounds such as áhi-han- ‘serpent-slayer,’ an epithet of Indra, ahi-hátya-, and áhi-ghna- ‘killing of the serpent.’

In addition to being morphologically and syntactically flexible, the formula is also subject to lexical variation: the noun áhi– is often replaced by vr̥tra– (literally ‘resistance, obstacle’), the name of the serpent-like demon and main antagonist of Indra. Finally, the formula can be expanded with the explicit expression of the subject (cf. índro in (3), anyáḥ ‘this’ in (4)) or with the mention of vájra– ‘club,’ Indra’s famous weapon, as in example (4):

(4) vájreṇa anyáḥ hánti vr̥tráṁ

club.INST DEM.NOM kill.PRS.3SG Vr̥tra.ACC

‘He strikes Vr̥tra with his club.’ (RV 6.68.3c)

Based on the examples presented so far, we can define the formulaic continuum concerning the slaying of the serpent as a construction that is lexically, syntactically, and morphologically flexible, which can be represented as follows:

| FORM | KILLV(han-) SERPENTObj |

| FUNCTION | MYTH OF THE SLAYING OF VR̥TRA |

The architecture of the Vedic Treebank and Sanskrit WordNet allows capturing the full range of morphosyntactic and lexical variants of the formula presented above.

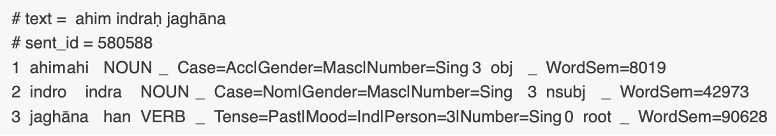

By enriching the Treebank with semantic information and using a simple query language like Udapi, it is indeed possible to extract all variants of the formula with a single query. The Vedic Treebank can be enriched with semantic information by adding the meaning (i.e., an Attribute=Value pair with WordSem as attribute and the synset ID as value) of each word in the miscellaneous field of the CoNLL-U format, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Semantic annotation added to the Miscellaneous field of the CoNLL-U format

This is a time-consuming task that is currently underway under the name of Sanskrit Sembank, i.e., the semantically annotated portion of the Digital Corpus of Sanskrit and thanks to the work of Oliver Hellwig. Once the semantic annotation is completed, it will be sufficient to run the following queries to extract all occurrences of the formula:

| N. | QUERY | READING |

| 1 | cat RV.conllu | udapy -TM util.Mark node=’node.form == “ahim” and node.parent.form == “ahann” and node.ord – node.parent.ord == 1′ | less -R | The form áhann and the form áhim adjacent to each other and in this order |

| 2 | cat RV.conllu | udapy -TM util.Mark node=’node.form == “ahim” and node.parent.form == “ahann”‘ | less -R | The form áhann and the form áhim; order and distance not specified |

| 3 | cat RV.conllu | udapy -TM util.Mark node=’node.lemma == “ahi” and node.parent.lemma == “han” and node.deprel == “obj”‘ | less -R | The lemma áhi– depends on the lemma han– as a direct object (obj) |

| 4 | cat RV.conllu | udapy -TM util.Mark node=’node.misc[“WordSem”] == “8019” and node.parent.lemma == “han” and node.deprel == “obj”‘ | less -R | A word with meaning ‘serpent’ depends on the lemma han– as a direct object (obj) |

| 5 | cat RV.conllu | udapy -TM util.Mark node=’node.lemma == “han” and len([x for x in node.descentants if x.misc[“WordSem”] == “8019” ]) == 1′ | less -R | A word with meaning ‘serpent’ depends indirectly on the lemma han– (‘serpent’ is a descendant of han-) |

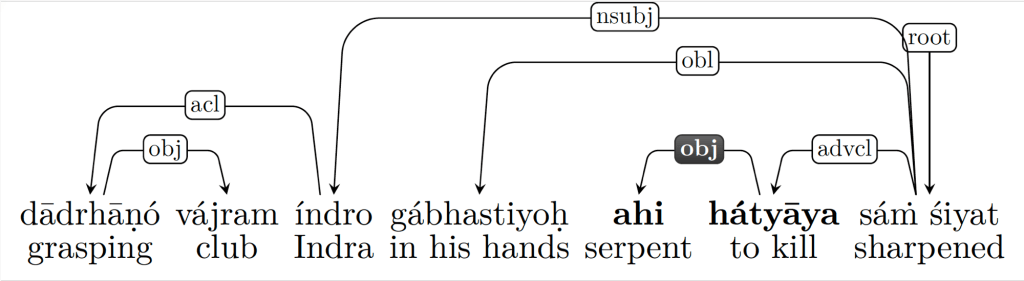

The first query identifies all occurrences of the expression áhann áhim, specifying the order of the constituents. The following queries allow for increasing levels of metrical (e.g., áhann … áhim), syntactic, and lexical flexibility. The third query captures all cases where áhi– ‘serpent’ functions as the direct object of the verb √han– ‘to kill,’ regardless of their specific forms: áhann (imperfect), jaghāna (perfect), jíghāṁsataḥ (desiderative participle), etc., for the verb; and áhim (accusative) and áhaye (dative) for the object. Additionally, thanks to the decision to split compounds and annotate their internal syntactic relations, the third query also captures compounds like ahi-hátyāya ‘for the killing of the serpent’ in (5). Figure 4 shows the syntactic structure of the compound and the sentence in which it occurs, as analyzed in the Vedic Treebank.

(5) dādr̥hāṇó vájram índro gábhastiyoḥ …

grasping.PTCP.PF.NOM club.ACC Indra.NOM hands.LOC.DU

ahi-hátyāya sáṁ śiyat

slaying-serpent.DAT PV sharpen.PRS.INJ.3SG

‘Grasping the club tightly in his hands, Indra sharpened it to kill the serpent.’ (RV 1.130.4a-c)

Figure 4. Syntactic tree of RV 1.130.4a-c

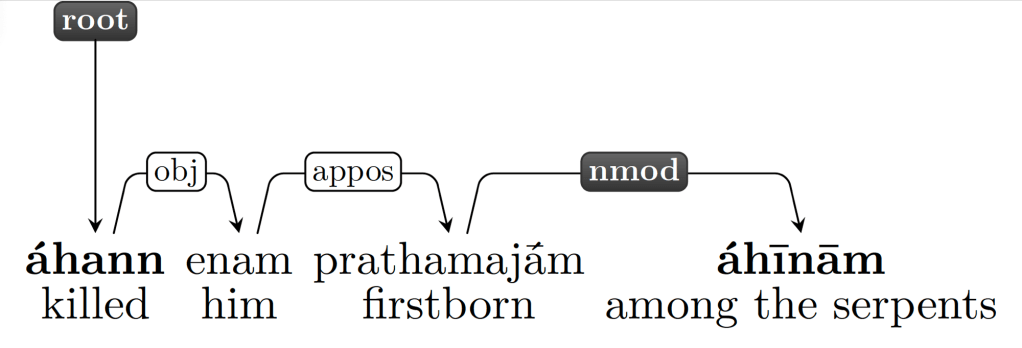

Finally, the fifth query again identifies a term for ‘serpent’ that depends on √han-, without specifying the type of relation and also allowing for the relationship to be direct or indirect (node.descendants); in other words, this query identifies the expressions mentioned above, but also expressions where the word for ‘serpent’ is not directly dependent on the verb √han-, but belongs to the same subtree. An example of this variant is presented in (6), where enam ‘him’ functions as the object of √han-, prathamajā́m ‘the firstborn’ depends on enam as an apposition (appos), and finally áhīnām ‘serpent’ depends on prathamajā́m as a nominal modifier (nmod). Figure 5 shows the syntactic structure of the sentence.

(6) áhann enam prathamajā́m áhīnām

kill.IMPF.3SG 3SG.ACC firstborn.ACC serpent.GEN.PL

‘He killed him, the firstborn among the serpents.’ (RV 1.32.3d)

Figure 5. Syntactic tree of RV 1.32.3d

Wrapping up

The methodology presented above allows us, starting from a CoNLL-U file containing morphosyntactic and semantic annotation of a text, to extract all variants of a formula once its semantics and basic structure are known. Given the high degree of repetition, the reader of the Rigveda often feels as though they are encountering formulas that have yet to be described in the literature. After introducing the theoretical framework underlying the methodology and the linguistic resources needed to apply it, I have shown in this post how to apply the methodology to the formulaic network KILL THE SERPENT. As mentioned above, enriching the Vedic Treebank with semantic information is a long endeavor, but the potential of such a resource suggests that the outcome is well worth the effort.

References

Hellwig, Oliver. 2010-2024. The Digital Corpus of Sanskrit. http://www.sanskrit-linguistics. org/dcs/index.php.

Hellwig, Oliver, Salvatore Scarlata, Elia Ackermann, and Paul Widmer. 2020. The Treebank of Vedic Sanskrit. In Nicoletta Calzolari, Frederic Bechet, Philippe Blache, Khalid Choukri, Christopher Cieri, Thierry Declerck, Sara Goggi et al. (eds.), Proceedings of The 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC 2020), 5137–5146.

Hellwig, Oliver, Sebastian Nehrdich, and Sven Sellmer. 2023. Data-driven dependency parsing of Vedic Sanskrit. Language Resources and Evaluation: 1–34.

Watkins, Calvert. 1995. How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2 thoughts on “Combining Digital Resources to Investigate the Oral-formulaic Diction of Sanskrit Texts (Part 2)”