The Malian radio station in Kayes, close to the Senegalese border, was founded in 1988, as part of an Italian cooperation program and in the context of an authoritarian state with a monopoly on information. However, the government authorised this first local radio station on the condition that it restricted itself to covering only cultural, developmental, and educational subjects. Since 1992, access to the airwaves has been liberalised, but the radio station, which covers a fairly vast zone including almost 400 villages, remained faithful to its editorial line. It transmits in four languages: Bambara, Soninke, Pulaar and Kassonke.

In 2017, Aïssatou Mbodj-Pouye, an anthropologist at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), moved to Mali to continue her long-term work on the mobility of African workers. She travelled west of Bamako, to Kayes, to work with the rural radio station and to analyse its migration-related programs. This encounter with the team of the Association des Radiodiffuseurs de Kayes pour le Développement Rural (ARKDR) and its collection of documents would considerably influence the anthropologist’s research.

Following initial work in collaboration with the Kayes radio team (the director, Darrar ben Azour Maguiraga, and the technicians: Mamadou Sow, Boubacar Sylla, Mamadou Sidibé, and Mamadou Demba Traoré), which still counts the pioneers from the 1990s, the idea emerged to digitise the entire collection of 260 cassettes in order to preserve this exceptional oral heritage. The UCLA library’s Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) funded this digitisation and made available more than 900 recordings; half songs and half radio programs. The Kayes radio website should also eventually host a copy of this collection.

Local work

All of the treatment was carried out locally and in-house. The $50,000 initial budget was managed locally. The main funding came from the Modern Endangered Archives Program of the University of Los Angeles Library in California. The project was also supported by a digital residency from the Huma-Num DISTAM (DIgital STudies Africa, Asia, Middle East) consortium and the Institut des mondes africains (IMAF-Aubervilliers). Radio technicians were trained by a Senegalese archivist, Hamet Ba (Cabinet d’Etudes, de Gestion et d’Expertise des Patrimoines Ecrits, Audiovisuels et Multimédias), to produce electronic files that met the required standards. And of course, ad hoc equipment was provided to carry out the work.

The question of rights and the re-documentation of the recordings

One of the conditions of funding by the American program was that the digitised audio documents be made available online. The tapes had been broadcast, some even many times, so the content was not particularly sensitive. It was first necessary to obtain the agreement of the radio station’s director and the local community leaders, which was easy. UCLA wanted also to respect the notion of copyright, so each song was listened to again, identified and all the performers credited. It even appeared necessary to scour the villages where the recordings had been made in order to get all those involved to sign agreements.

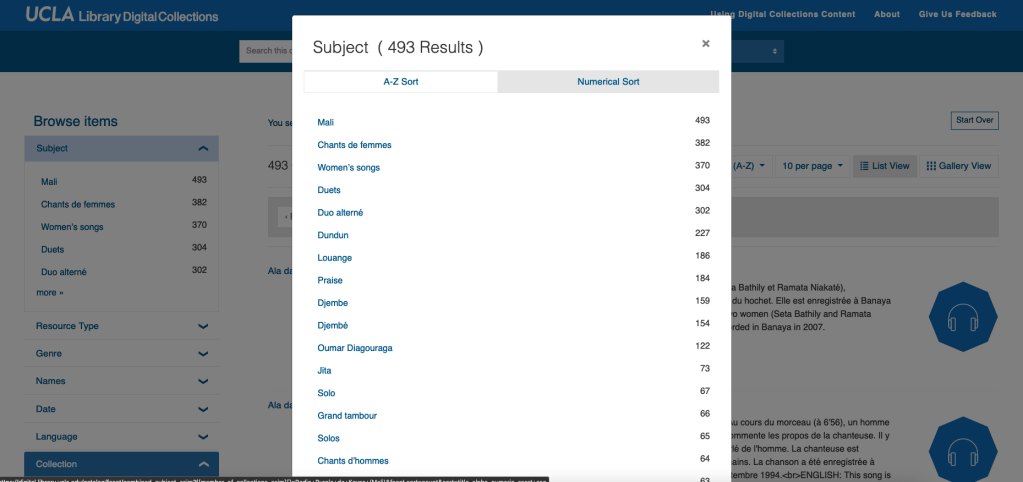

Then the collective idea arose to set up a team of cultural mediators who could help to re-document the recordings, inform people about the project, and, lastly, collect permissions from the interpreters. The team of cultural mediators was coordinated by Barka Fofana. It included Maly Bâh, Waly N’Diaye, Mamadou Konaté, and Abdoul Wahab Traoré. For 917 music files, 535 authorisations were requested, resulting in 42 refusals and 493 authorisations; for 424 files it was not possible to locate the persons or visit the locations due to the lack of security in the region.

Metadata and the ageing of terminologies

The descriptive metadata involved a huge amount of work spent listening to each of the recordings, whether radio broadcasts or songs. Teams based in Mali, Senegal, Mauritania, France, and the United States worked to accurately describe these audio documents, creating an extremely well-documented collection. It was necessary to bring together people competent in each of the four vernacular languages, but also capable of describing in French or English. Fabrice Melka (CNRS) and Aïssatou Mbodj-Pouye took over all these descriptions and standardised them at Institut des Mondes Africains, in Paris.

The current context has nevertheless rendered certain documents and terminology obsolete or sensitive. This is particularly the case with references to slavery, which was still very much a part of the social structures inherited at the end of the 20th century and was not a heavily politicised issue at the time of recording. Today, however, this status is considered to be infamous, and it is not acceptable for people to be publicly associated with descendants of former slaves. This terminology has been therefore amended in the descriptions. Other terms that are now considered to have colonial connotations, such as “tribe” or “marabout”, could pose a problem, but the editors decided to respect the choices made in local French, in the African context and by African actors. Ultimately, in the translation into English that was necessary for the American site to go online, the vocabulary rooted in a version of French shared across Francophone Africa was rendered in standard English.

Consultation

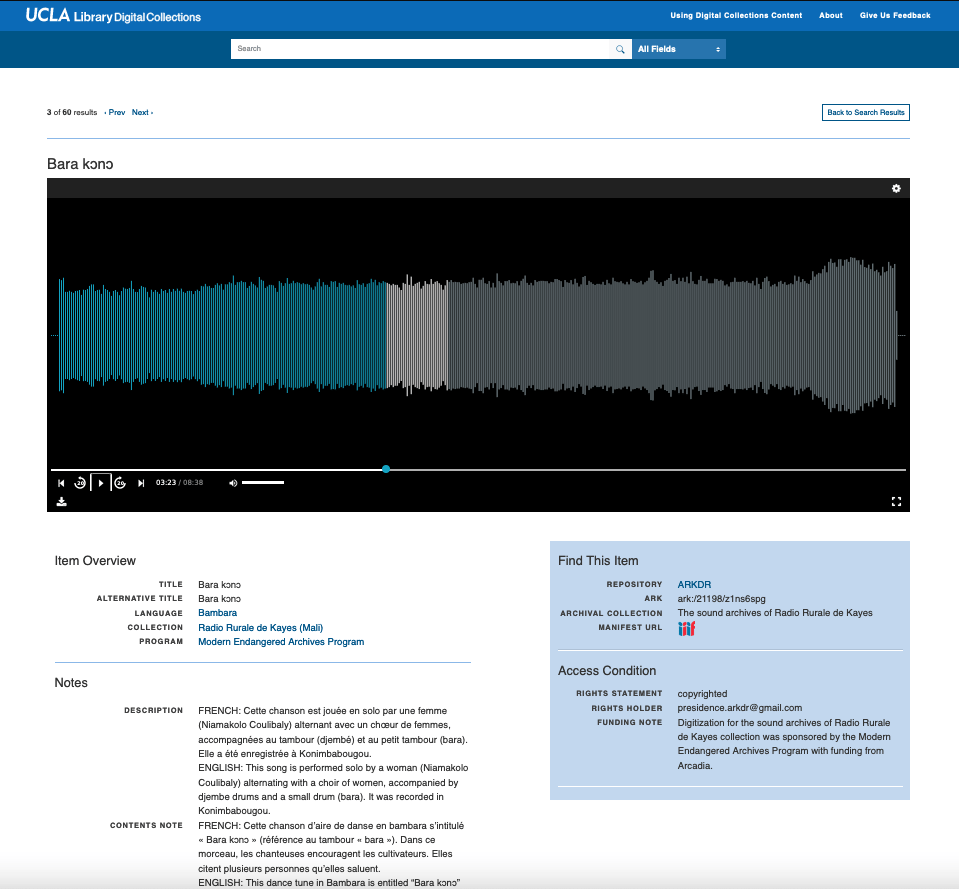

The consultation interface is relatively simple. Records can be filtered by subject, name, language or date. Then, for each one, the full descriptive metadata is displayed in French and English. A short description is followed by a lengthy description of the content of each file.

Of course, files can be listened to and downloaded. The quality of the sound recording is most often of very good quality. For some items, the cassette call number is displayed, helping to maintain the link between the original physical object and the digital file. This also makes it possible to reconstruct the recordings that were kept together on the same unit for cassettes with such a number.

This project, which has now been completed, brought together Malian communities, French and African researchers and American heritage and funding institutions, with a strong emphasis on local expertise.

One thought on “Digitising the Archives of a Rural Radio in Mali: A Transnational Project”