This is a guest post by Anna Osterlow. See bio at the end of this post.

When looking at current scholarly and media discourses on new technologies in Africa, there appears to be what Kanyinsola Obayan, researcher of Nigerian computer history calls a “hypervisibility of innovation from Africa and the Global South”. This hype about the African tech sector, however, seems to present a dualistic picture: with either booming tech hubs in African metropoles and success stories of African entrepreneurs on the one side or criticism about a persisting global digital divide on the other side.1 The latter points to the unequal access to ICTs in the Global South. Further, recent debates raise awareness concerning the exclusion in the development of AI and other digital tools, often not designed to work with non-Western languages or in non-Western contexts. Thus, new projects about more inclusive AI come up, developing speech recognition, translation programmes and other AI tools for African languages. Other efforts are raised towards innovations that bring tech solutions “by Africans, for Africans” and include apps and gadgets that respond to the particular needs of people in an African rural area, city or region.

While there is no doubt about the relevance of such tech developments and discourses they often miss out on a crucial aspect, namely, a historical perspective. Looking at the histories of computing and informatics in Africa reveals that ideas about technologies adapted to African contexts and languages are indeed not new but have a history that leads us at least back to the 1980s (and beyond).

One example takes us to the University of Dakar in Senegal and starts with an interdisciplinary and international team that worked with micro-computers. This team at the University of Dakar claimed that to be useful in Senegal, computer software had to be developed by Senegalese experts and according to Senegalese culture. The leader of the team, a female informatician working at the Ministry for Scientific and Technical Research in Senegal, criticised that most computer software was developed according to Western socio-cultural contexts and was hence not reflecting African realities.

Therefore, the scientists in the project developed a Senegalese version of the software for microcomputers. The software they intended to “Senegalise” was called LOGO and worked as a learning program to teach children how to program a microcomputer. Initially, it was developed in English and for American school children, by Seymour Papert, a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States. Amongst other American scientists, the project in Dakar further included researchers from Paris, France who were working at the French Centre Mondial Informatique et Ressource Humaine (World Centre for Computing). On the Senegalese side, the team was comprised of computer scientists, pedagogues, teachers and government authorities from the Ministry of Scientific and Technical Research.

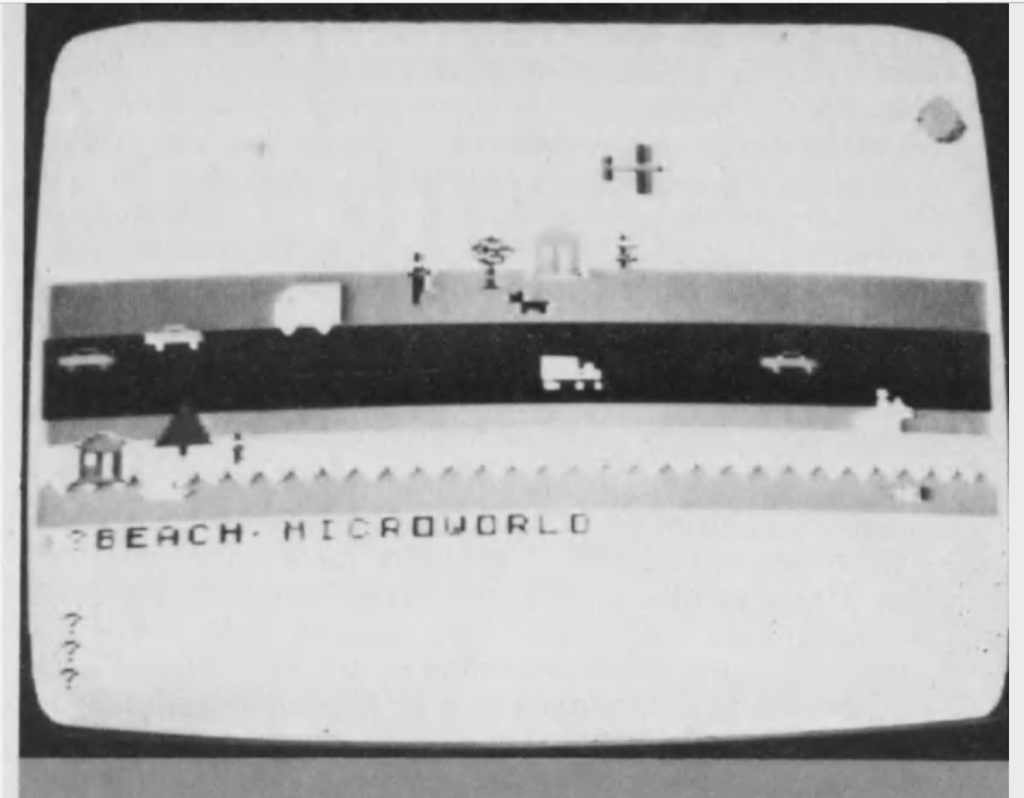

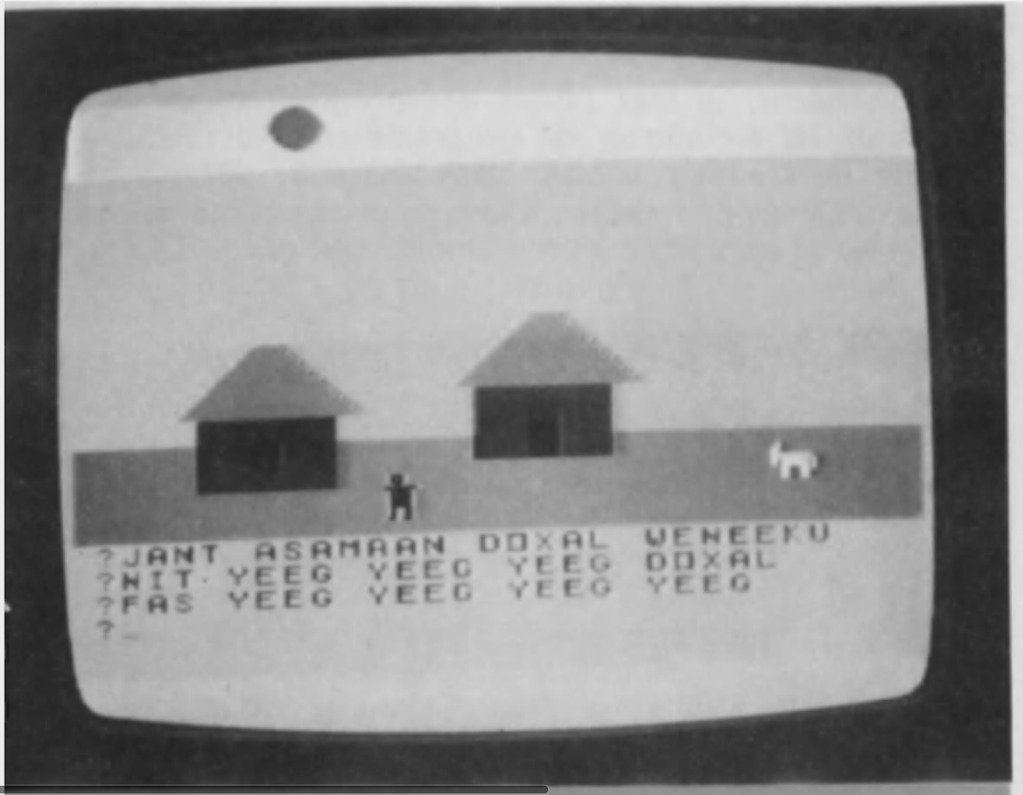

One of the versions of LOGO was a programme called “microworlds”, in which the user could programme a landscape with moving objects, for example, a “beach world”, with cars on a street, people at the beach, and other elements. While in the original LOGO version, the commands were given in English, the Senegalese team developed a version in Wolof, one of the main languages spoken in Senegal. What is more, they designed a “microworld” which, according to them, came closer to the everyday life of the Senegalese children.

Pictures: The American “beach world” (above) and the Senegalese microworld (below).

Beyond the software, the Senegalese members also demanded that computer hardware should be fitting Senegalese and on a larger scale, African contexts. Like contemporary African tech innovators developing apps that respond to specificities like rural environments and unstable internet, they argued at international meetings and conferences for the development of African hardware. Therefore, a regional African institute should be set up, where local experts design and adapt computer technology to African realities. Further, computer producers who wanted to export their technology to African countries had to comply with specific norms. For example, the computers should be resistant to high temperatures, or dust.

This presents just one of the many cases of early African tech pioneers who come to the fore when looking closer at the history of computing in Africa and there are other examples which can be traced back to the 1960s and beyond.

Yet, the current digitalisation debates on new technologies in non-Western contexts provide a strong image of newness, which forgets about the former aspirations, hopes, and imaginations related to technologies. In Nigeria, the computer centre of the University of Ibadan catalogued archaeological findings for its department as early as 1964 and today, new tools seem to take up the same promise when offering solutions for digital heritage preservation for African artefacts and culture.

Considering the histories of African tech tools and historical uses of informatics in non-Western contexts would allow us to grasp the seemingly new trends in more depth and it would bring to the fore the African partakers who shaped technological developments at their beginnings. Like historian Obayan highlights for Nigeria, unfortunately, these former efforts often go unnoticed in current debates. At the same time, the existing research on computing history often disregards African contexts. There is hence a double blindness about the African pathways to the digital age that has to be overcome by paying closer attention to the history of “tech in Africa”. This might also lead to a greater understanding of the hierarchies that are still determining the global spread of technology today, and that would link the efforts of the Senegalese team in developing software in Wolof to today’s efforts of building digital tools for non-Western languages.

Cover photograph by Bob Mohl.

- See, for example, Nicolas Friederici, Michel Wahome, and Mark Graham, Digital Entrepreneurship in Africa: How a Continent Is Escaping Silicon Valley’s Long Shadow (The MIT Press, 2020), https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/43517; Fanny David and Quentin Velluet, ‘Alex Okosi (Google) : « L’Afrique doit être au centre de la révolution de l’IA » – Jeune Afrique.com’, Jeune Afrique, 4 June 2024, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1574015/economie-entreprises/alex-okosi-google-lafrique-doit-etre-au-centre-de-la-revolution-de-lia/; and Nnamdi Oranye, Disrupting Africa. The Rise and Rise of African Innovation, ed. Ryan Peter, Africa Is Open for Business (Leipzig: Amazon Distribution, 2016).

↩︎

References

Fanny David and Quentin Velluet. “Alex Okosi (Google) : « L’Afrique doit être au centre de la révolution de l’IA ».” Jeune Afrique, June 4, 2024. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1574015/economie-entreprises/alex-okosi-google-lafrique-doit-etre-au-centre-de-la-revolution-de-lia/.

Nicholas Friederici, Michel Wahome, and Mark Graham. Digital Entrepreneurship in Africa: How a Continent Is Escaping Silicon Valley’s Long Shadow (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020). https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/43517.

Kanyinsola Obayan. “Entrepreneurial Hustle and the Rise (and Fall) of Personal Computer Companies in Lagos, Nigeria: 1960–1999.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 44, no. 3 (July-September 2022): 6-16. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2022.3182631.

Nnamdi Oranye. Disrupting Africa: The Rise and Rise of African Innovation, ed. Ryan Peter (Leipzig: Amazon Distribution, 2016).

Lorela Viola and Paul Spence (eds.). Multilingual Digital Humanities (1st ed.) (London: Routledge, 2023). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003393696.

Anna Osterlow is a doctoral researcher at the Centre for History of Sciences Po in Paris, France. Her thesis investigates the histories of early computing in Senegal and Nigeria from a transnational perspective. She is currently a fellow in the Interdisciplinary Network for Technology and Entrepreneurship Research in Africa and a member of the Scientific Committee of the Africa Programme at Sciences Po. Anna formerly was a research assistant at the Leipzig Research Centre Global Dynamics, where she worked on research projects about the use of drones in Africa and digitalisation dynamics in agriculture.

One thought on “African Tech Inventions, Inclusive AI and Digital Innovation: A Historical Perspective”