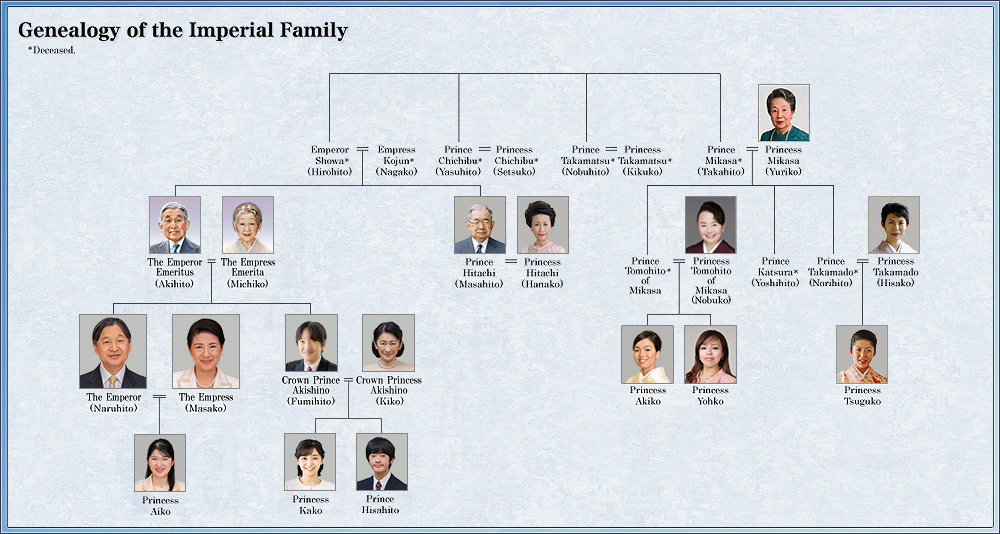

The Imperial Household Agency is the government administrative body with jurisdiction over the Imperial Family of Japan. It is also Japan’s leading institution for the preservation of cultural property, and is well known for the compilation of the Tennō Kōzoku Jitsuroku 天皇皇族實錄 [Records of the Emperors and the Imperial Families][1] and the operation of its digital archive system, the ‘Archives and Mausolea Department Catalog and Image Disclosure System’.[2] In addition to the official or private duties of the Imperial Family, which include visits to museums and cultural heritage sites, the promotion of traditional handcrafts and performing arts, and Shinto rituals at the Imperial Palace, Imperial Mausoleums and Tombs, and Grand Shrine of Ise, many members of the Imperial Family are researchers active in academia. Several of them are researchers in the humanities and social sciences, for example, Emperor Naruhito 今上天皇 is a historian with a master’s degree, Crown Princess Kiko 皇嗣文仁親王紀子 of Akishino 秋篠宮 is a psychologist with a PhD, and Princess Akiko 彬子女王 of Mikasa 三笠宮 and Princess Hisako 憲仁親王妃久子 of Takamado 高円宮 are art historians with PhDs. The activities of the Imperial Household Agency and the Imperial Family are therefore of crucial importance to the humanities in Japan.

Traditionally, the fact that successive emperors have an absolute spiritual significance has also set them apart from foreign monarchies, which are more active in opening information. However, in the spring of 2024, the Imperial Household Agency opened an official Instagram account, an unusual move that took many by surprise. There is the common impression that the Imperial Family is mysterious and shrouded in a veil of chrysanthemums. This is partly due to the influence of traditional values, which consider it taboo to portray the royals in a light-hearted manner. However, the biggest factor, in my personal opinion, is the fact that the Constitution of Japan prohibits the emperor from making political statements, they cannot express their private opinions in public and their freedom of speech is extremely restricted. It means no matter how unreasonably they are slandered, they are not allowed to directly refute that slander.

Some malicious gossip papers and anonymous websites have caused problems. In the past, Empress Emerita Michiko 上皇后 and Empress Masako 皇后 developed aphasia and adjustment disorders because of public reactions to malicious gossip articles, including fake news.[3] The Imperial Household Agency has adopted a policy of refuting reports that are untrue, but to be honest, it has been quite reluctant to do so. While some have defended the Imperial Household Agency as caught in a dilemma between the Imperial Family and the people,[4] some critical experts have said that the Agency is not a defender, but a hostile organisation that only monitors the Imperial Family[5] and that now similar bad history is repeating itself.

A major catalyst that forced the Imperial Household Agency to enter the world of social media was the issue of former Princess Mako’s 眞子内親王 marriage. As many of you will remember, she married a Japanese man in 2021. Her husband was a very unpopular and notorious man, and there were various associated scandals.[6] He left to study in the US without giving any explanation, causing much public disbelief, but the Imperial Household Agency did very little. In 2020, Princess Mako’s father, Crown Prince Fumihito 皇嗣文仁親王 of Akishino, said that Princess Mako’s partner needed to explain in good faith the truth or falsehood of, and the circumstances surrounding, a series of allegations including his family’s financial troubles, etc., and the Emperor also supported the Crown Prince’s statement. These unusual statements by the Emperor and the Crown Prince showed the Imperial Household Agency to be inept. In response, Mako’s partner published a written defence.[7] However, public dissatisfaction exploded because the document was unusually long and did not contain an apology to the Imperial Family for the trouble he had caused. Only the Director-General of the Imperial Household Agency admired his texts as ‘well written,’ and many experts were dismayed and satirized.

On social media, not only Princess Mako’s husband, but also the Akishino household and Princess Mako herself became the target of criticism, and the situation was flooded with privacy violations and falsehoods. As a result, Princess Mako developed PTSD. In general, it goes without saying that Mako’s husband had big problems, but the Imperial Household Agency’s ineptitude made it seem as if these issues were someone else’s business. These are probably the direct reasons behind the Imperial Household Agency’s rethinking of its public relations approach.

Back to the topic of social media. Why did the Imperial Household Agency not choose X, which has the highest penetration rate among the Japanese? More and more public authorities around the world are withdrawing from X in response to the dramatic increase in hate speech and fake news postings.[8] In particular, X’s online space by Japanese-language accounts is the worst situation. Some social media influencers even say to be wary of anonymous accounts in Japanese. Anonymous accounts from both the right and the left regularly abuse each other and post false information daily. Meanwhile, attacks on prominent figures, including researchers, online, such as sharing personal information, sexual harassment, harassing phone calls, and threats to their workplaces, are common. Moreover, excessive cancelling could be seen as suppression of freedom of speech. Some of these accounts are like malicious diploma mills, like ‘foundations’ with no legal status. Such situations made some Japanese researchers decide to suspend their X accounts. This is particularly the case with regard to topics in the humanities that can be linked to present-day political debates surrounding topics such as WWII. For example, because of the variety of thoughts and ideologies that exist in Japan regarding the dropping of atomic bombs, comfort women, war responsibility, kamikaze attacks, Yasukuni Shrine, etc., the dissemination of information by museums and other research institutions related to these topics always had to be done with caution.

In the past, such debates were mainly limited to TV programmes, newspapers, and magazines and conducted only by researchers, pundits, politicians, or famous activists. However, with the spread of the internet since the 2000s, it has become possible for everyone to join the debates. On highly anonymous noticeboard sites, it was no longer uncommon to see merely the exchange of illogical abuse. In the last decade, such stages have shifted from noticeboards to social media, where the user population and social influence have become significantly stronger. In the case of the topic about Japanese monarchy, as the Imperial Family is currently standing on the verge of extinction, with only three princes, including the Crown Prince, some argue that the princesses should be allowed to be able to inherit the throne, or that former royals who were removed from the line of succession by the US occupation forces in 1947 should be reinstated.[9] However, for the aforementioned reasons, various anonymous accounts that dislike the Akishino household have advocated for the dethronement of the Crown Prince and attacked researchers who support the return of former members of the Imperial Family as ‘sexist.’ In other words, the X discourse space is not a place where one can have constructive academic discussions on sensitive topics, including the succession to the throne. In these circumstances, it is not practical for the Imperial Household Agency to start an X account and it would seem unwise to do so in the future.

So how does the Imperial Household Agency operate on Instagram? They have disabled the DM and comment functions and post daily public activities by the Emperor and Empress and their daughter Princess Aiko 愛子内親王, as well as museum exhibitions. Their approach to social media stands out to people because it balances the monarchy’s traditional, formal image with the demands of contemporary digital transparency and accessibility. They currently have about 18 million followers. The New York Times noted that the posts are very similar to the content of the Imperial Household Agency’s official website and are not novel or flashy.[10] The Guardian stated that fans expecting selfies, emojis and casual private photos may have been disappointed.[11] However, it is pointed out that the choice of Instagram was appropriate in that it allowed users to turn off comments on posts.[12] The analysis[13] that the relationship between the monarch and the people in Japan is also more respectful and reverential than in Europe, and that the Imperial Household Agency only needs to manage its brand to minimise misinformation, is very much on point. In my personal view, this is a reasonably effective PR exercise for the younger generation, who have less contact with traditional media such as television and newspapers.

On the other hand, Instagram posts relate only to the Imperial House, and have never featured other members of the Imperial Family from the branch families of Akishino, Hitachi 常陸宮, Mikasa and Takamado. Some people have complained that this is the Imperial Household Agency’s account, not that of the Imperial House, and that the other royals, who are performing many official duties on behalf of the Empress while she is ill, are not featured. The Imperial Household Agency has stated that it may post on members of Akishino household in the future. It is unfortunate that the Akishino household does not appear when one of the reasons for entering the world of social media was slander against the Crown Prince and his families. Furthermore, the Imperial Household Agency does not adequately promote that the Crown Prince and others are involved in many activities, including exhibitions of important historical properties, awards for researchers including in the humanities, artistic activities by the physically challenged, speech contests in sign language, and memorials for the war dead, etc.

There is also the question of which accounts should be following back. The Imperial Household Agency has a policy of following back the accounts of foreign royal families, but currently, they only follow the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the Commonwealth, and Spain. How do they respond to other royal accounts? Or what about the personal and former royal accounts, or former monarchs such as the Romanian royal family? The presence or absence of following back could affect diplomatic relations.[14] Care should be taken not to tarnish the principle of the Imperial Family, which upholds equal treatment of all nations regardless of size or level of development.

In addition, even after the launch of Instagram, the Imperial Household Agency has been largely unable to take effective measures against fake news and malicious slander. Just recently, for example, the Imperial Household Agency remained quiet despite an anonymous site being set up to slander the Crown Prince and his family and call for DNA testing (it was quickly shut down when a writer announced legal action against them). The premise is that it may be difficult to expect too much from the Imperial Household Agency, which, unlike the Ministry of the Imperial Household before pre-WWII, is just an administrative agency of the government, to acts as the guardian of the imperial family. A key can be found in the Commonwealth monarchy‘s social media. The British Royal Family, which used to commit to philanthropy as a tradition, did not actively promote it because of its motto to act modestly. However, the death of Princess Diana triggered an anti-monarchy outcry, which led to a change in policy towards proactive disclosure. Specialists in information operations, including those from aristocratic backgrounds, rather than officers of the state, are responsible for the public relations strategy, such as social media as the guardians of the royal family, rather than as just the administrative staff. It is extremely important for Japan to learn from these methods to disseminate information more accurately.[15]

Finally, is there a possibility that the Imperial Household Agency may enter another social media platform in the future? The risks of X are as mentioned above. LinkedIn and Bluesky have few Japanese users. TikTok has security and data protection issues. Facebook, Threads, and Instagram are provided by Meta. Traditionally, there is a tendency for the Imperial Family to respect neutrality and impartiality in all situations so using only a particular company’s platform is strange. In this light, the most likely platform now might be YouTube.

As the Imperial Household Agency continues to engage with social media, their actions raise questions about how tradition and modernity intersect in digital spaces. What strategies can institutions employ to balance preservation (of cultural heritage, traditional culture, or religious custom, etc., for example) with the demands for transparency and public engagement?

References

[1] About the Tennō Kōzoku Jitsuroku, see Hirohito Tsuji, ‘Japan Knowledge: Tennō Kōzoku Jitsuroku, Records of the Emperor and the Imperial Family’, The Digital Orientalist (2023). Available at: https://digitalorientalist.com/2023/12/26/japan-knowledge-tenno-kozoku-jitsuroku-records-of-the-emperor-and-the-imperial-family/

[2] About the Archives and Mausolea Department Catalog and Image Disclosure System, see Hirohito Tsuji, ‘Japan’s Imperial Household Agency: The Archives and Mausolea Department Catalog and Image Disclosure System’, The Digital Orientalist (2024). Available at: https://digitalorientalist.com/2024/03/26/japans-imperial-household-agency-the-archives-and-mausolea-department-catalog-and-image-disclosure-system/

[3] Ben Hills, Princess Masako: Prisoner of the Chrysanthemum Throne. (New York: Penguin Group, 2006).

[4] Kenneth J. Rouff, Japan’s Imperial House in the Postwar Era, 1945-2019. (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2020).

[5] Tsuneyasu Takeda, ‘Kunaichō Chōkan ga Kōshitsu no Kōhōkan to Iu Akumu’, The Seiron 606. (2022): 296-299.

[6] About the scandal, see Alison J. Miller, ‘The Princess and the Press: Mako’s Wedding and the History of Imperial Women’, criticalasianstudies.org Commentary Board (2022). doi: 10.52698/NTLZ1233

[7] Full text is available at: https://www.asahi.com/images21/fbox/edit5/202102/20210408123948.pdf

[8] Kanae Nakahara, ‘Kunaichō ga Kentō Shiteiru Kōshitsu Twitter Koko ni Kite Daimondai ga Okiteiru Wake: Īron Masuku to Iu Nankan’, Gendai Bijinesu (2024). Available at: https://gendai.media/articles/-/124458

[9] About contemporary discussions on the Chrysanthemum throne, see Ben-Amy Shillony, Enigma of the Emperors: Secred Subservience in Japanese History. (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2005).

[10] Kiuko Notoya, Mike Ives, ‘Japan’s New Royal Instagram Page Forgoes Flash for Formality’, The New York Times (2024). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/02/world/asia/japan-royal-family-instagram.html

[11] Justin McCurry, ‘Bonsai Trees and A Royal Birthday: Japan’s Imperial Family Dips A Careful Toe in World of Instagram’, The Guardian (2024). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/01/japan-imperial-family-instagram-posts-emperor-naruhito-empress-masako-princess-aiko

[12] Julian Ryall, ‘Japan’s Royals Are Joining Instagram: With Kate Middleton’s Cancer Saga in Britain Top of Mind?’, South China Morning Post (2024). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3256853/japans-royals-are-joining-instagram-kate-middletons-cancer-saga-britain-top-mind

[13] Frances Mao, ‘Japan’s Imperial Family Latest Royals to Join Instagram’, BBC News (2024). Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-68710938

[14] See [8].

[15] Naotaka Kimizuka, ‘Naze Kunaichō wa Kōshitsu Goikka no Insuta o Hajimeta no ka: Nikagetsu de Hyakuyonjūman Nin Forō o Tebanashi de Yorokobenai Wake’, President Online (2024). Available at: https://president.jp/articles/-/82325?page=1

One thought on “PR Strategy and Social Media of Japan’s Imperial Household Agency”