The Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean & Egyptian Miracles of Mary Project (PEMM), hosted by Princeton University, aims to bring together the miracles of the Virgin Mary that have circulated in the cultural space of Ethiopian Christianity since the medieval period. Miracles, an extremely popular genre in Ethiopian Christianity, are fairly short texts, in which trivial or unusual situations are resolved by a miraculous intervention, in our case that of the Virgin Mary. They are written in Ge’ez, the classical Ethiopian language. They form collections that vary significantly in size and composition. Some miracles are widespread, while others are rare. In quantitative terms, this is a substantial corpus of both textual and iconographic material, with more than a thousand different Marian miracles. However, exhaustive descriptive tools for these materials have so far been lacking.

The legacy of W. F. Macomber and the first dematerialised collection of Ethiopian manuscripts (EMML)

The first attempt to draw up a list of these many miracles predates the advent of computer tools. In the 1970s, a vast project was launched to microfilm Ethiopian Christian manuscripts held in monastic, private, and heritage libraries in Ethiopia. It was carried out over more than 20 years by the Ethiopian National Library, the Ethiopian Orthodox Patriarchate and the Hill Monastic Microfilm Library, resulting in a collection of some 9,000 black and white microfilms of Ethiopian manuscripts, known as the EMML (Ethiopian Monastic Microfilm Library) collection. This was gradually catalogued, with the first cataloguers being Macomber, soon joined by Getatchew Hayle. While the extent of the corpus of the Miracles of Mary in Ethiopia had already been noted, notably by Enrico Cerulli, William Macomber was the first, in the 1980s, to attempt to draw up what he hoped would be an exhaustive list. He compiled an index of 643 miracles, including the incipit (the beginning of the text), a bibliography when the miracle was published and/or translated, and the shelf number of the manuscripts in which the miracle was found (in the EMML collection and in other collections worldwide). This work remained unpublished and was deposited with Macomber’s scientific archives at HMML.

While discovering this first list, Wendy Laura Belcher, from Princeton University, and her team conceived the idea of using IT tools to make this work accessible and to extend it. This is how the Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean & Egyptian Miracles of Mary Project (PEMM) came into existence in 2018. The aim is to use the possibilities offered by databases to create links between the manuscripts containing compilations of Marian miracles. These manuscript witnesses are all different – it is their very characteristic to be unique in essence – and yet share many common features.

From spreadsheets to the database: How to link and display objects, texts and images?

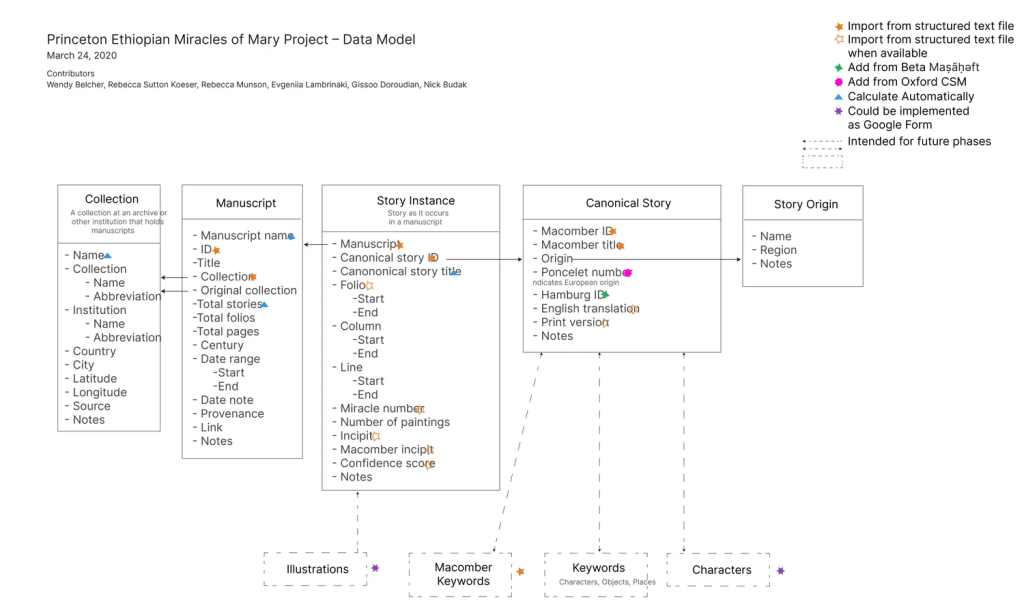

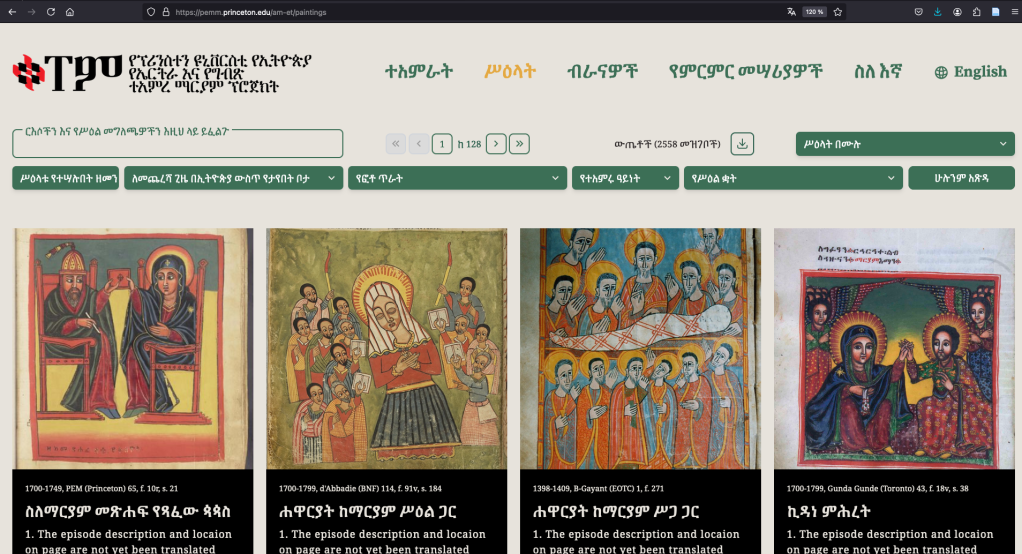

To date, the database contains 1,000 manuscripts from 105 institutions and collections, and 2,500 illuminations, for a total of 1,000 miracles, more than half of which have been translated into English. This database was started out as spreadsheets, as Rebecca Koeser’s detailed article (on setting up a ‘lightweight relational database’ using Google spreadsheets, 2021) explains. Later on, it migrated to an SQL database managed by a CMS.

Fig. 1: PEMM Data Model (also available here).

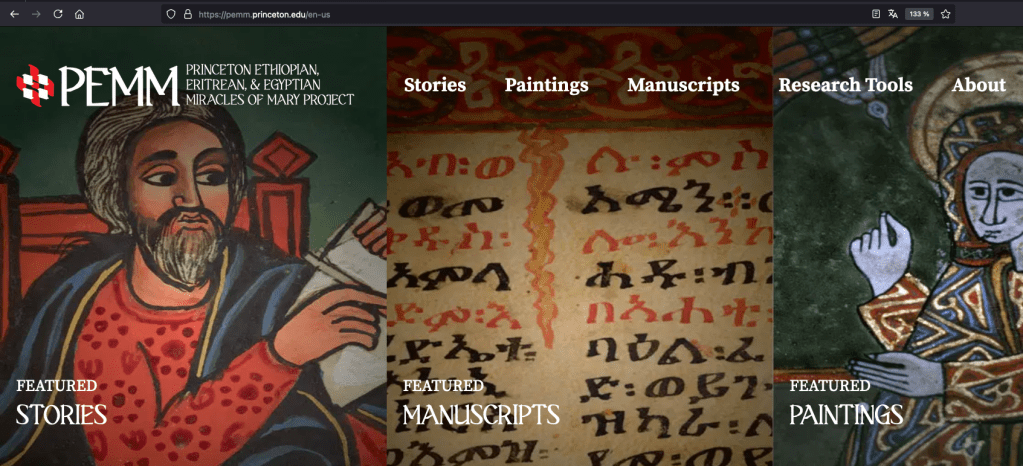

After six years of work, the website went online in January 2024. The user interface offers a wide range of functions. First of all, it provides three very different and complementary ways to access the corpus: you can search in the images, manuscripts or miracles. Each allows you to query the corpus with specific questions, as each one is made up of specific metadata (with faceted filters to sort the results of queries if desired).

Fig. 2: Three ways to access the corpus: stories, paintings and manuscripts.

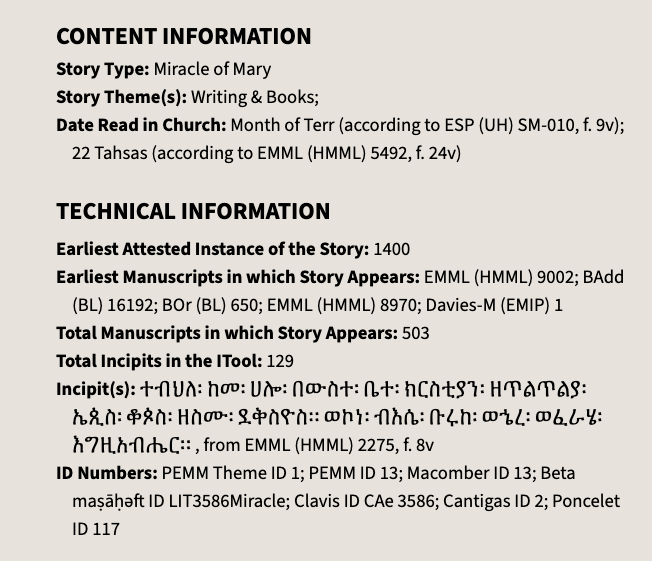

Given the wealth of information, I take only one example of navigation: that by the text, or “story” level, which is probably the most innovative in this project (although searching by image is also very useful and, in the context of Ethiopian studies, very innovative). Each text is given a unique identifier by the project associated with the identifiers of the Beta Maṣaheft (BM) project, which has established a clavis of Ethiopian texts. Similarly, when a miracle has a French or European origin, it is linked to the clavis established in 1902 by Poncelet, which served as the basis for a database of Latin Marian miracles created in 2005 at Oxford. It is to some extent the model for PEMM, but one technological generation earlier, and therefore with different technological and scientific choices. For instance, it is not possible to run a query by ID to look for all the miracles with a Poncelet ID.

Fig. 3 : https://pemm.princeton.edu/en-us/stories/13

In the “Story” database, the PEMM search engine is limited to searching the titles and translations of the miracles (provided that they exist, of course). Among other things, this query interface highlights the manuscript witnesses into which a given miracle has been copied; an essential use of this tool. Admittedly, the BM project is intended to provide the same information in the long term, but the advantage of the PEMM project is that it focuses exclusively on manuscripts of Marian miracles, whereas BM catalogues all Ethiopian manuscript documentation. In any case, the PEMM project offers very different metadata and functionalities to BM. For instance, it is possible to immediately view all the images of a single miracle in the former. This works, of course, insofar as the manuscripts are digitised, but it also shows just how fast things are progressing in this area! There is no mention on the website of whether the images are called by a IIIF protocol or stored on their own server. Also, one small drawback of the navigation is that when you’re on a miracle page, you cannot click on the PEMM ID number, nor return to the database, but the back button takes you to the previous search.

It is also on the pages dedicated to a miracle that the English translation of the Ge’ez text is found. The translation is based on a single handwritten witness, which avoids the problem of variants when a miracle is known through several witnesses.

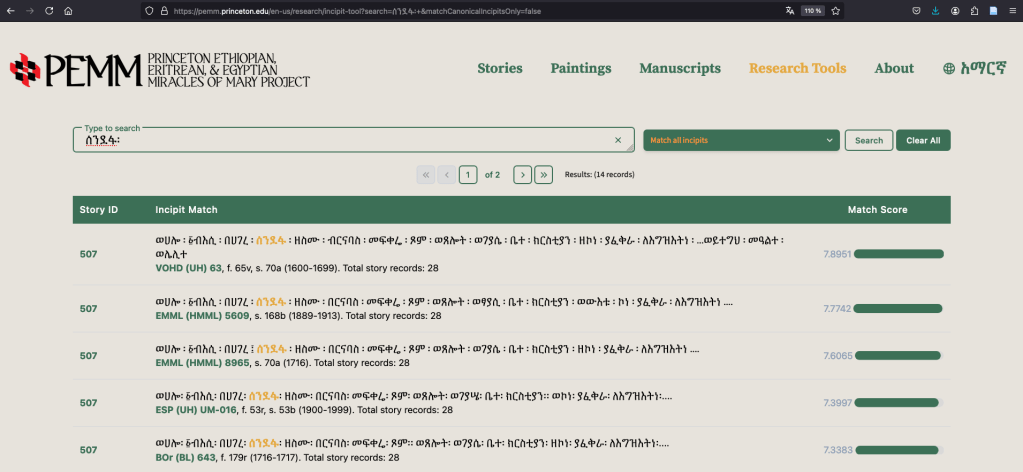

In addition to the three navigation modes mentioned above (by miracle, by manuscript and by image), there is also the ‘incipit research tool’. This allows you to search for a miracle by the first few sentences of its story and, more generally, to search any words in the incipits’ corpus. This additional tool, initially developed in-house to help identify stories, is now available to all users.

Fig. 4 : Searching for the word ሰንደፋ in the incipit tool.

A generous access granted to the metadata

The project also makes its data available in the Zenodo warehouse, and this repository will be updated annually. After a quick examination of the downloadable data, it appears that these excel tables contain more data than is accessible online, for instance the Poncelet IDs that are not searchable on the website can be accessed in the CSV files. But conversely, I did not find in these CSVs the ‘themes’ that are used as descriptors for images and miracles, and that appear in the consultation interfaces. The way these themes have been defined and labelled is not explained anywhere, and it is not possible to filter the results based on them. The ‘Using the PEMM website’ page does not yet explicitly say anything about them. Concretely speaking, one theme is ‘Patrons and churches’ but there is no information about how these labels are assigned and none of the CSV files downloaded so far seem to contain them. So we can see that there is a scientific and analytic approach, but without any possibility to make profit of it. Similarly, the label ‘Royal manuscripts’ is displayed in the faceted filter of the manuscript search, but there is no way of knowing what defines a codex as royal in nature. Therefore, the analytic categories are for the time being somewhat opaque and their usefulness remains low.

The good thing is that anyone can take part in this ambitious project by pointing out mistakes or suggesting improvements using the feedback form.

Inclusiveness

The website is entirely in Amharic, which may be useful for Ethiopian schools and for Ethiopian clergy who have access to digital tools but not to English. For the time being, the Amharic version is less extensive than the English version. For comparison, see this page in Amharic and the same page in English.

Here the English version can be found by searching the word “Sandafa”, the name of the town in Egypt where the famous church of Dabra Metmaq was located. A search using the same keyword in the Ethiopic writing system “ሰንደፈ”, on the other hand, yields no results, as this term does not appear in the titles translated into Amharic, nor in the (shorter) abstracts. Additionally, there are currently no translations of the miracles into Amharic . So the immense effort already made on the English side of the website must be extended, and the bravery of the whole enterprise must be acknowledged!

One thought on “Ethiopic Miracles: A Database to Link Images and Texts of Marian Miracles”