This year’s Editor’s Digest for Chinese Studies falls right after the Chinese New Year, so first of all let me use this opportunity to wish our readers a prosperous and peaceful Year of the Snake! Spring Festival is all about reuniting with your family, and retrospecting Digital Orientalist posts from last year brings a similar sentimental feeling – and what a year it was!

A lot has happened since my last digest. With Machine Learning and Large Language Models (LLM) becoming widely adopted for research purposes, the technological complexity of our work rapidly grows, and the topics of our team’s posts reflect that.

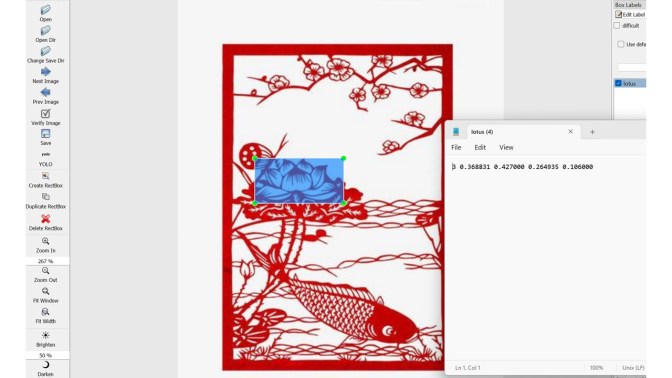

Lu Wang talks about the possibilities behind computer vision based on her project, which uses open-source resources to train a model to detect and compare floral patterns on Chinese papercuts, modern and historical. Another post on computer vision was written by Eric H.C. Chow, who explores Gemini PRO LLM for Chinese OCR and metadata extraction, comparing it to other popular OCR solutions. His experiments with Chinese news clippings showed promising results with LLM being able to successfully fulfill complex tasks – although not completely error-free.

His next post, written in collaboration with Greta Heng, looks at a different type of task performed by LLMs – namely, the extraction of linked data related to historical places from texts written in a mixture of Classical and Modern Chinese. The authors methodically go through their working process to show how prompt construction and choice of language to address the model can influence the output – and what types of errors are usually made by the LLMs when attempting to turn loosely organized multilingual texts into structured output.

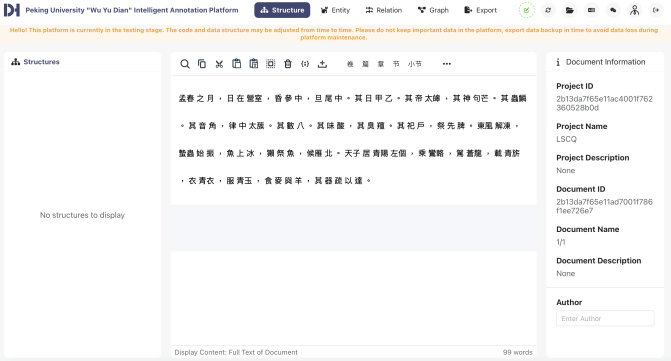

In the past year, the Chinese Studies team has also produced quite a few posts that aim to introduce our readers to new tools and the concepts behind them. The very basic introduction to Python and Chinese text pre-processing I created together with Tilman Schalmey provides a small tutorial on basic programming concepts aimed to be accessible to those with a humanities background. Gian Rominger shows the WYD platform, developed by Peking University’s Research Center for Digital Humanities, that is able to split Classical Chinese texts into words and automatically place punctuation, which is often absent in pre-modern texts. This is yet another LLM-based service, so although it does not always perform well with more complex tasks like named entity recognition, it is expected to continuously learn and get better with time.

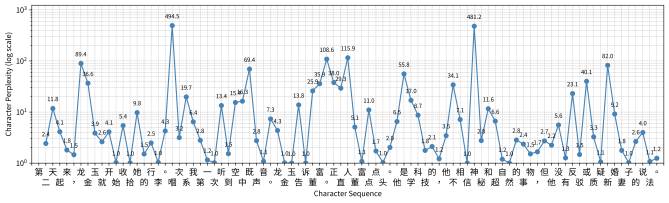

Next, our new team member Maciej Kurzynski discusses how LLM-based technologies can be used in Cognitive Stylometry. He talks of language models as “average humans” and how this understanding of them can lead us to new research questions. As an illustration, he used them to see how modern Chinese novels deviate from this “average”, and what this can tell us about the writer. The readers are invited to try out the code in a Jupyter notebook linked in the text.

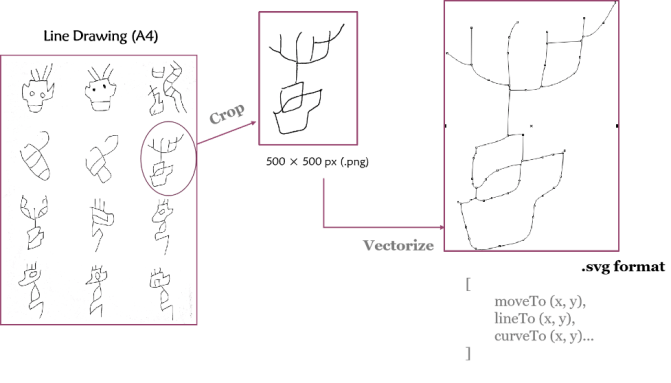

Nevertheless, new tools and resources don’t have to rely on AI to be exciting and significantly simplify a researcher’s workflow. A great example of this is the Jingyuan platform, introduced to our readers by its creator, Peichao Qin. The platform features an impressive array of tools to work with Shang oracle bone inscriptions. The first post describing this resource concentrates on the creation of a downloadable oracle bone font (a welcome improvement of the existing practices) and a glyph database with multiple search and filtering options. The second post is dedicated to a different technology behind the platform, the visualization of the storage locations of known artifacts. This text can also double as a tutorial on how to create one’s own geographical visualization using Leaflet.js, as it features advice on how to prepare data, and code snippets.

Last but not least are reviews of archives and databases, old and new. Henry Jacobs talks about the famous China Biographical Database (CBDB), its structure and intended uses. Coupled with a list of tutorials and guides and a first-hand commentary from the CBDB executive committee chair Peter Bol, this text can be a good starting point for exploring the resource.

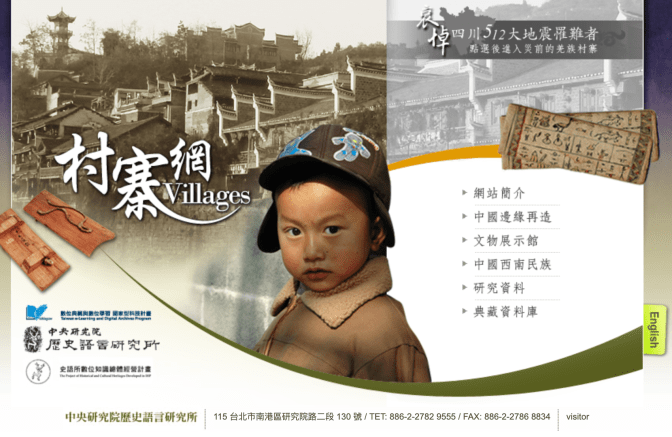

In a guest post, Wei-chieh Tsai introduces a large digitization project of ethnographic materials on Chinese minorities collected during the first half of the 20th century. The website of the project offers access to photographs taken during fieldwork, documents, and images of artifacts. Unfortunately, it does not have an English version, but with the help of Wei-chieh Tsai’s translations, even those who do not read Chinese can make use of the materials.

And those who work with Tangut literature will be delighted to (re-)read Enfu Zhang’s post on the Index of Tangut Literature 西夏文獻目錄 Database that collects information on extant Tangut texts previously only available in print or as pdf files. Available as a webpage, this index allows one to easily locate manuscripts in international collections and auctions, based on various search criteria.

Although digitization and preservation of materials is still a crucial part of our work, the year 2024 also brought us a plethora of publications on implementing new technologies and making peace with Large Language Models becoming a part of our research routines. There are still a lot of concerns surrounding AI in academia – completely justified – but I take a lot of pleasure in seeing our field positively embracing the new. As one can see from our publications, LLMs can be a great way to outsource mundane tasks and to make digital methods more accessible: a carefully crafted prompt can now replace many lines of code. This year’s Chinese Studies team still has a lot to say about their experiments – and I am looking forward to seeing what they have in store.

One thought on “Editor’s Digest January 2025: Chinese Studies”