Decades ago, one of the main concerns of the cultural heritage community was the lack of digitized data. Although digitization is still an issue in many cultural institutions and efforts and funds are allocated to this cause, challenges on how to manage, represent, and sort through the bulk of data have been an ongoing concern for both providers and users.

In an attempt to create technologies directed specifically at managing cultural heritage data with all its complexities, several knowledge management systems have been developed in recent years. In a previous post, I introduced the Arches platform as one such system. In this post, I will go into ResearchSpace; an open-source semantic research environment for cultural heritage data funded by the Andrew Mellon Foundation.

The development of ResearchSpace was initiated in 2009, and the latest version of it (ResearchSpace 4.0.0) was released in December 2024. This latest version contains features that make the process of knowledge representation relatively easy for non-technical users. The interface has also become really user-friendly in comparison with other platforms.

There is no fundamental limit on the area of study or the scope of data in the design of ResearchSpace as an infrastructure, and it can be used in handling data in various fields. However, here I will focus on its use in representing historical data, which is a complex issue when it comes to the field of cultural heritage. We will look into how ResearchSpace can facilitate working with historical data.

An overview of ResearchSpace and its design

ResearchSpace is at its core a platform for contextualizing knowledge. The platform is designed with the idea that in the process of given research, especially historical research, researchers aim to represent the complexity of a specific subject in the real world by producing narratives that can contain contexts and thinking processes. This important aspect of research is however lost when we attempt to transform our non-structured data i.e., textual narratives to digital structured data. ResearchSpace introduces two fundamental features that address and resolve this issue: knowledge graphs and and semantic expressions.

1. Using knowledge graphs and the logic behind it

For the purpose of providing a more comprehensive way of transforming our human knowledge into processable constructs, ResearchSpace implements knowledge graphs. In the context of ResearchSpace, a knowledge graph is defined as “A continually changing informational structure that mediates between a human, the world, and a computer” (ResearchSpace documentation). In practice, a knowledge graph is used to store and represent data in a network of meaningful relations as opposed to conventional databases and spreadsheets.

The logic behind implementing this approach is explained by Oldman, Tanase, Santschi (2019). They argue that conventional databases are designed with a quantitative mindset, prioritizing efficiency, standardization, and scalability over contextual richness. This results in what they call “thin information systems”—structured data models that record isolated facts but lack meaningful relationships, historical depth, and interpretative layers. These systems, while useful for cataloging and referencing, struggle to support dynamic, evolving research environments where knowledge is complex and constantly shifting.

ResearchSpace on the other hand takes a fundamentally different approach by implementing a “thick information system” through its knowledge graph framework (figure 3). Instead of imposing rigid technological abstractions that force researchers to adapt to predefined structures, ResearchSpace builds on patterns of knowledge that align with humanistic and scientific research methods. This allows data to be expressed in a way that is more natural to scholarly inquiry—capturing not just facts but also interpretation, belief, and argument (Oldman 2019).

The core principles of this thick system include:

- Structured yet qualitative data: ResearchSpace enables structured data representation while maintaining the richness of qualitative research.

- Contextual integration: The knowledge graph allows diverse and heterogeneous data sources to be meaningfully connected across disciplines.

- Dynamic knowledge representation: Information is treated as an evolving process rather than a static dataset, preserving chains of interpretation over time.

- Open-ended knowledge growth: Scholars can expand and refine knowledge without rigid constraints, fostering long-term sustainability and collaborative participation.

By shifting from thin systems that store isolated facts to thick systems that represent knowledge as a dynamic, interconnected web of meaning, ResearchSpace creates an environment where scholarly inquiry can thrive. Its knowledge graph is not just a storage mechanism but a living structure that evolves with research, mirroring the way human knowledge itself develops.

2. Semantic expressions with ontologies

Through built-in semantic expression capabilities, ResearchSpace allows researchers to build the aforementioned knowledge graphs. A data point (like a place) is not treated as a static ‘entity.’ Rather it is recognized as a dynamic ‘process’ interwoven with a multitude of relationships across time and space. This is achieved through semantic enhancement, where existing data can be mapped to event-based ontologies, specifically the CIDOC CRM.

CIDOC CRM is a comprehensive ontology that continues to expand with specialized adaptations and it is widely used in cultural heritage and other fields. It offers a contextual framework that allows diverse information to be integrated while preserving its complexities.

In ResearchSpace a thoughtfully designed user interface makes the ontology accessible to non-technical users. This allows users to begin by adding a new resource based on the CIDOC CRM ontology. For instance, they can start by selecting a Human-Made Object and gradually provide more details, such as its creator, production date, and other relevant attributes. All applicable relationships (properties) from the CIDOC CRM ontology are displayed and can be added, enabling the description of a wide range of entities. Through this interface, data entry is seamlessly integrated with modeling, allowing users to build complex semantic data networks.

Using ResearchSpace

The default UI of the latest version of ResearchSpace offers some user-friendly features that make it easy to navigate through different parts of the system. A description of all the features is provided in the release note of the current version. The default codebase contains almost every feature needed to record cultural heritage data. Nevertheless, it is possible to configure the system based on specific requirements. Describing data with this version basically follows a select-import workflow, which eliminates a big part of the technical challenges for cultural heritage experts.

To illustrate how ResearchSpace can be used to structure and explore cultural heritage data, let’s consider an example. A fascinating Persian luster mihrab (prayer niche) from Meydan Mosque in the city of Kashan in Iran is held in the Museum für Islamische Kunst (museum of Islamic art) in Berlin. It was taken in the late 19th and early 20th century from Iran to England and later to Germany.

The history of this object is shaped by a network of people, events, and places that played a role in its displacement from a standing building to a museum. The mihrab and its history have been the subject of study by several art and architecture historians, providing a rich body of knowledge in the form of textual narratives. In order to transform this information into structured data using the ResearchSpace semantic narrative approach, we need a number of CIDOC CRM classes and properties as the underlying framework for description. Some of the key classes for this purpose are mentioned below. However, more descriptions can always be added using other CIDOC CRM classes to express other aspects of the object in question.

- E22 Human-Made Object and E12 Production, E11 Modification cover descriptions about the luster mihrab as an object.

- E7 Activity and its subclasses of E8 Acquisition, E9 Move, and E10 Transfer of Custody cover descriptions of movement and ownership changes of the mihrab.

- E39 Actor

- E53 Place and E52 Time-Span allow us to express the time and places in which activities took place.

| Name | Relations to other entities | Textual reference |

| Creation of Kashan mihrab (E12 Production) | P108 has produced → Kashan mihrab (E22 Man-Made Object) | The luster mihrab is signed by al-Ḥasan ibn ‘Arabshāh and dated 623/1226, from the Masjid-i ‘Imād ad-Dīn at Maidān-i Sang in Kashan (Ritter 2017, 157) |

| P4 has time-span → 623 AH / 1226 CE (E52 Time-Span) | ||

| P14 carried out by → al-Ḥasan ibn ‘Arabshāh (E21 Person) | ||

| Acquisition of the Mihrab by John Richard Preece (E8 Acquisition) | P22 transferred title to → John Richard Preece (E39 Actor) | It was the Englishman John Richard Preece (1843–1917) who had acquired the mihrab and sent it to England, with help from his colleague Stainton. […] Although no published source mentions a precise date, it is clear from the travel accounts above that the mihrab must have been taken from Kashan between 1889 and 1900. (Ritter 2017, 157) |

| P4 has time-span → between 1889 and 1900 (E52 Time-Span) | ||

| Moving Kashan mihrab to Wimbledon (E9 Move) | The collection [of John Richard Preece] went piece by piece to the residence of his brother, Sir William Preece, in Wimbledon and was said to have counted a thousand objects. Some of them, including the lustre mihrab from Kashan, were shown to the British public in 1905 in the South Kensington Museum in London. (Ritter 2017, 157) | |

| P25 moved → Kashan mihrab (E22 Man-Made Object) | ||

| P26 moved to → Wimbledon (E53 Place) | ||

| 1905 Exhibition of Kashan mihrab at the South Kensington Museum (E7 Activity) | P7 took place at → South Kensington Museum (E53 Place) | |

| P4 has time-span → 1905 (E52 Time-Span) |

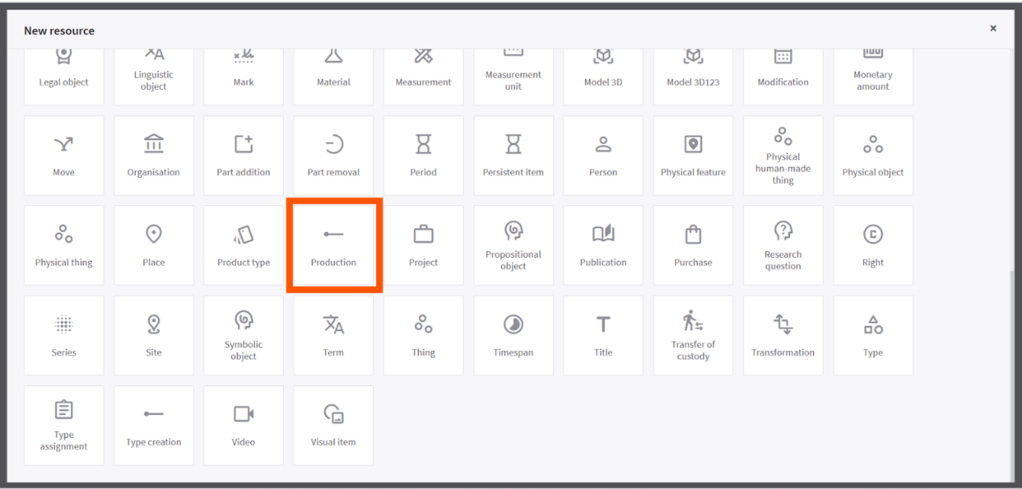

In ResearchSpace this information can be imported by simply creating a new resource of the production class (figure 1).

Figure 1. A list of pre-defined CIDOC CRM classes (resources in ResearchSpace)

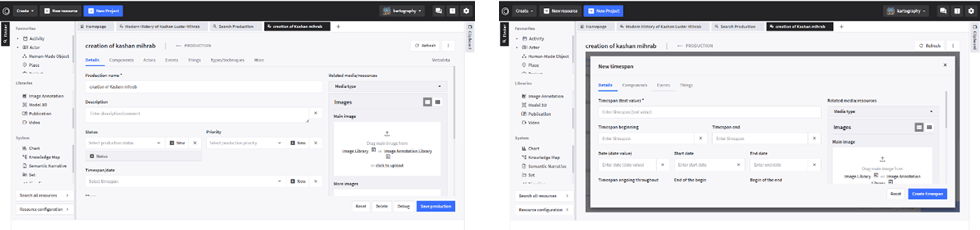

In the default interface of ResearchSpace, this production resource has already been set up to correspond to the E12 Production class of CIDOC CRM, so all the classes and properties that can be used in relation to this class are pre-defined by default. The nested-form template (figure 2) of the resource page allows the user to create new appropriate instances of any related entity as the production instance is being developed. This feature makes the process of mapping with CIDOC CRM rather fast and easy.

Figure 2. The nested-form template of ResearchSpace

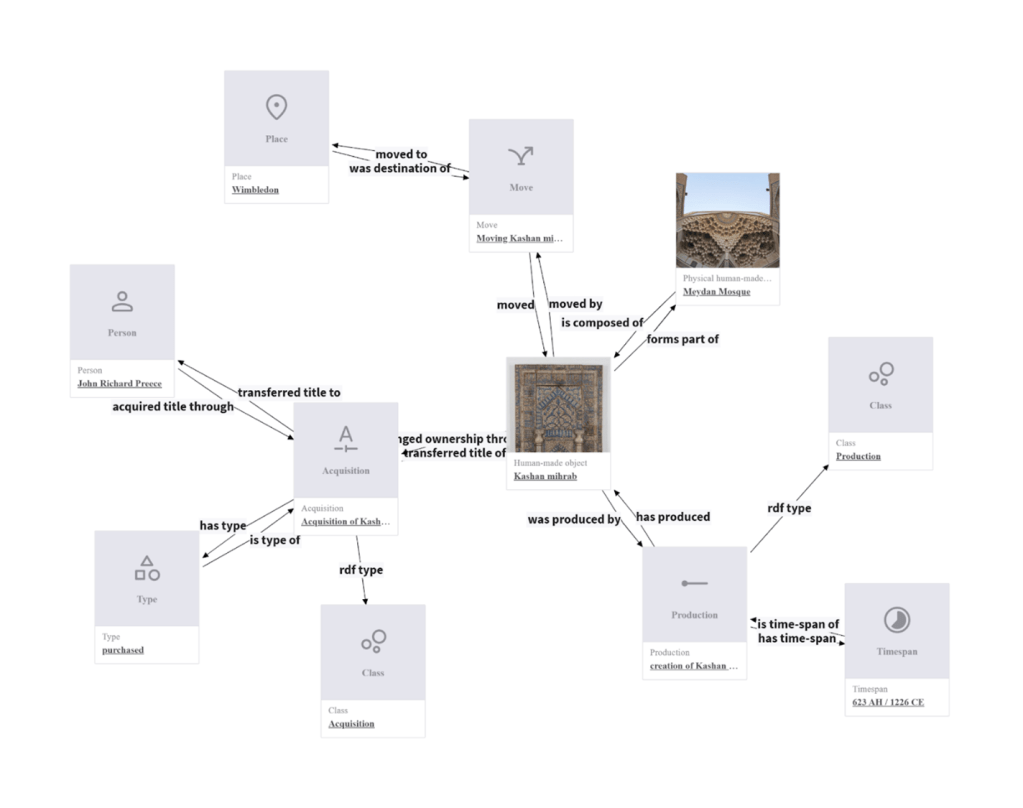

The Knowledge Map function of ResearchSpace (figure 3) provides a visual representation of this complex data, making it easier to explore relationships between the object in question, events, people, and places. By exporting the data about the Kashan mihrab, including its production, movement, acquisition, and exhibition history, we can analyze its provenance and historical significance in a clear, interconnected format.

Figure 3. Representation of a part of the the network in ResearchSpace knowledge map

ResearchSpace 4.0.0 stands as a powerful tool for structuring and contextualizing cultural heritage data in a way that preserves its complexity and historical depth. By integrating semantic technologies such as CIDOC CRM and providing user-friendly interfaces, it enables researchers to build rich, interconnected knowledge graphs that go beyond traditional databases. The ability to visually map and export data through features like the Knowledge Map function further enhances its usability, making it an invaluable asset for cultural institutions, scholars, and heritage professionals. As the volume of digitized heritage data continues to grow, platforms like ResearchSpace play a crucial role in ensuring that this information remains meaningful, accessible, and adaptable to evolving research needs.

References

Dominic Oldman et al., “The Problem of Distance in Digital Art History: A ResearchSpace Case Study on Sequencing Hokusai Print Impressions to Form a Human Curated Network of Knowledge,” International Journal for Digital Art History, no.4 (2019): 5.29-5.45. https://doi.org/10.11588/dah.2019.4.72071

“Knowledge Graphs and Patterns,” ResearchSpace, accessed March 11, 2025, https://researchspace.org/knowledge-graph-and-patterns/.

Markus Ritter, “The Kashan Mihrab in Berlin: A Historiography of Persian Lustreware.” In Persian Art: Image-Making in Eurasia, edited by Yuka Kadoi (Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 157–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474469685-013.