In her essay “Why Are the Digital Humanities So White? or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation,” Tara McPherson makes a provocative argument: that the very architecture and logic of computation, particularly as it developed in the post-WWII era in the United States, are deeply intertwined with and reflective of the era’s emergent racial logics, specifically the shift towards a “colorblind” yet still segregational racial formation.

McPherson’s is a structuralist argument: the modular, compartmentalized, and seemingly neutral design principles of systems like UNIX are homological with how race has been managed and discussed in post-Civil Rights America. As UNIX breaks down complex tasks into discrete, independent modules and separates the shell from the kernel, society treats racial issues as isolated incidents or individual prejudice, rather than systemic phenomena. This “lenticular logic”—called so after 3D postcards which show different images depending on the viewing angle, with only one being visible at any given moment—allows for coexisting racial realities while obscuring their interconnectedness and overarching power systems, thereby stifling collective struggle for justice.

A great deal has changed since 2012, when the essay was first published in Debates in the Digital Humanities (ed. Matthew K. Gold; available open-access), not least the global landscape of digital humanities itself, which now presents new contexts for both reinforcing and challenging such embedded logics. In particular, the rapid development of area studies and digital humanities in East Asia calls for much more attention than it has been given so far in anglophone academia.

For example, I have just come back from Shanghai, where I had an opportunity to give a talk at Tongji University’s Center for German Studies (同济大学德意志联邦共和国问题研究所), a site of many burgeoning DH initiatives. A series of hands-on workshops that preceded the lecture introduced students to computational methodologies, including AI-enhanced topic modeling, collocation analysis, and multilingual sentiment classification. While Baidu AI Studio is still a few steps behind Google Colab and Kaggle, and PaddleNLP is unlikely to replace Huggingface Transformers in the near future, the eagerness among scholars to apply DH methods to humanities research surpassed anything I have experienced outside China.

Tongji is just one example: all over the PRC, new Area Studies and Digital Humanities centers emerge with scholars eager to employ AI and statistical tools to research cultural phenomena beyond China’s borders. With state-sponsored digitization of resources at a scale incomparable to any other part of the world, large language models orders of magnitude cheaper than their Western counterparts, and active support for cross-disciplinary learning (all undergraduates at Peking University, for instance, learn to code), the institutional and scholarly support for Digital Humanities is something that many non-China-based researchers can only dream of. Platforms like the “吾与点” integrate advanced multimodal deep learning models for processing text and images, supporting tasks like automatic knowledge graph construction, intelligent table extraction, and RAG-based applications. It remains to be seen how much interpretive effort will be put into those massive resources, but already now the enthusiasm is striking.

My intention here is not to add yet another “China and the West” (or “the Rest”) comparison. In fact, I want to question it. China’s area studies boom is not immune to the critiques of imperial complicity previously leveled against its Western counterparts. While the latter emerged without AI and petabytes of data, “foreign studies” in China can forge an even more seamless alliance with the state and reduce the understanding of other peoples into abstract statistics. Like in the West, it will also produce what Willem van Schendel called “area lineages”—self-enclosed scholarly communities interacting solely within their academic fiefdoms. What I would like to suggest is that while digital humanities might reinforce the modular logic identified by McPherson, they also hold the promise of bringing those different modules (or areas) back into conversation.

For instance, modern language models consist of multiple layers and subnetworks, each of them aggregating different information and paying attention to different aspects of the data. Each word generated by a language model is a result of millions of neurons interacting with each other. The structure of LLMs thus invites scholars to reconsider cultural phenomena as multi-layered and poly-temporal, reversing the lenticular logic of segregation and deconstructing the East-West divide. My recent article (“Poly-Temporal, Multi-Layered: A Techno-Cognitive Theory of Narrative Experience in Literature”) analyzes a passage from Zhang Xianliang’s 1985 novel Half of Man is Woman to explore precisely this confluence, suggesting how computational approaches, informed by cognitive science, can help us trace such co-existing layers and their distinct, yet interwoven, temporal signatures. Zhang’s novel is simultaneously an expression of authorial needs, shaped by his immediate experience of the Cultural Revolution; a product of specific cultural backgrounds, reflecting contemporary social and political currents during the early post-Mao era; an articulation of bodily patterns anchored in deep evolutionary history, influencing neuroaffective responses and schematic understanding; and even a manifestation of the grammatical and linguistic properties of the language in which it has been composed, which themselves have their own distinct historical trajectories.

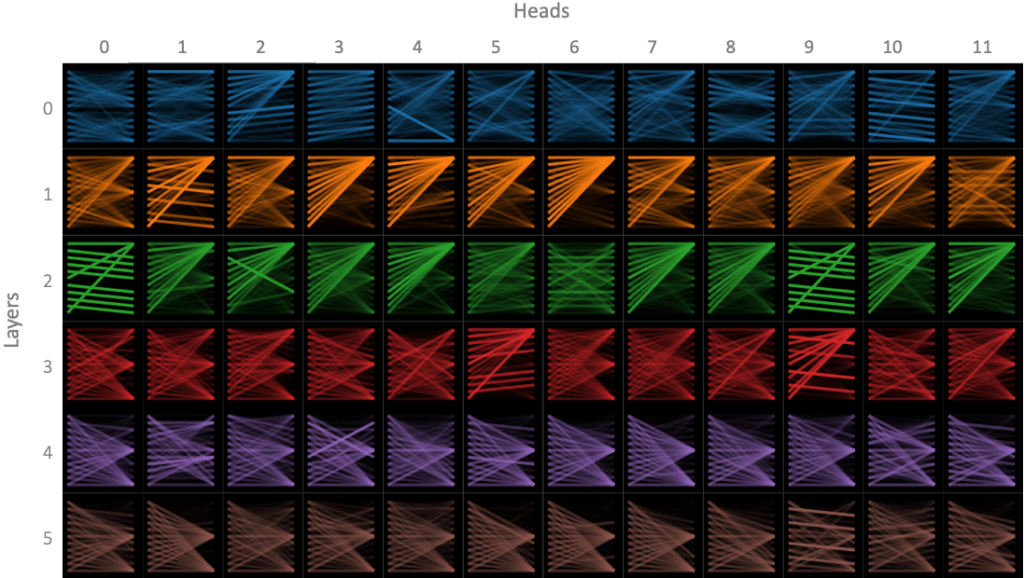

Figure 1. The self-attention mechanism in BERT. Each token in the input sequence pays different amount of attention to other tokens. This process is distributed across multiple layers and multiple “heads” within each layer.

The multi-layered, poly-temporal approach also speaks to the question of how to deal with the persistent Euro-Amerocentrism of theory. Should we, as often debated, develop altogether new models that generalize from the empirical distinctiveness of Asian histories? The “Asia as Method” strategy, despite its attractiveness, is easily appropriated by essentializing nativist and nationalist agendas. This is not a hypothetical problem: a recent review of my article submitted to an Asian Studies journal, for instance, argued that “fictionality” is not a Chinese concept and therefore cannot be used to analyze cultural phenomena in the PRC. Another review argued that “neurons” are not universal.

The techno-cognitive theory is an attempt, one of many, to reimagine literary and cultural studies in the twenty-first century. By fostering methodologies that inherently invite both native and non-native perspectives, such a model holds the promise of broadening interpretive authority, moving beyond frameworks where a limited number of senior scholars and sage-kings steer the discourse. Literary scholarship in area studies would traditionally take a corpus of texts and their historical context as inputs to produce an interpretation. This f(texts, history) = interpretation model (or 文史研究 in Chinese) has yielded strikingly similar discussions of broad concepts like “modernity” across diverse literary traditions, embodying almost verbatim the logic of the 3D postcard. From the techno-cognitive perspective, by contrast, literary “history” becomes a record of changes introduced as texts are alternately integrated (encoded into multi-layered representations) and linearized (decoded into sequential text for transmission) by human writers and readers who operate within multiple hermeneutic circles. This process defies any single chronology.

The import of computational technologies into area studies scholarship might reshuffle the field, break open the self-enclosed scholarly communities, create space for new ideas, and foster genuine interdisciplinary collaboration, shifting our understanding of literature and culture from linear input-output mappings towards dynamic, recursive, and poly-temporal phenomena where here and there meet.

Or at least, such is my hope.