Celebrity diaries constitute an essential resource for researching modern Japanese history. Scholars examine the diarists’ lives, thoughts, social networks, and their reflection and involvement in contemporary events through their own narratives (Tsuchida 2011; Mikuriya 2020 [2011]). In addition to the people they encountered, celebrity diaries, in particular those of politicians and businessmen, often mentioned the names of ryōtei and charyō, where they would convene with their colleagues. However, it is difficult, if not impossible, for readers to ascertain the background and location of these restaurants. In the final post of this series, I will address how this challenge could be surmounted by employing the NDL’s full-text search system, thereby deepening our understanding of the spatial politics in wartime Tokyo.

Teahouse Politics (machiai seiji) and Spaces at the Dawn of the Pacific War

In late 1941, Matsumoto Gaku, a member of the House of Peers, frequently assembled with Fujiyama Aiichirō (a businessman and head of the Fujiyama concern), Captain Ishikawa Shingo, Naganuma Kōki (a Ministry of Finance official), and Kuboi Yoshimichi and Funada Naka, both were members of the House of Representatives at the time. Matsumoto recorded in his diary that he dined with these individuals three times between November and December, at three different venues: the Sugar Industry Hall (Tōgyō kaikan) at Yūrakuchō, Hachiryū at Shimbashi, and the Kinsui Honke at Hirakawachō (Shōyu kurabu 2021).

They probably chose to gather at the Sugar Industry Hall because Fujiyama was president of Dai Nippon Sugar Industry, one of the largest companies in the sector before 1945 (Higuchi 1947). Hachiryū was a renowned machiai, its first okami was a former geisha and the mistress of Magoshi Kyōhei. Magoshi worked for Mitsui Bussan for almost three decades in the late 19th century, which could explain why Hachiryū was frequented by Mitsui executives during the Meiji period (Ōtsuka 1935; Gamō 1956; Higuchi 1961). When Fujiyama Aiichirō and Matsumoto gathered at Hachiryū, Fujiyama Dōzoku, the holding company of the Fujiyama concern, was one of the major investors in the Mitsui zaibatsu-related corporations (Higuchi 1947). It remains uncertain, however, whether Hachiryū sustained strong ties with Mitsui during the early Shōwa years.

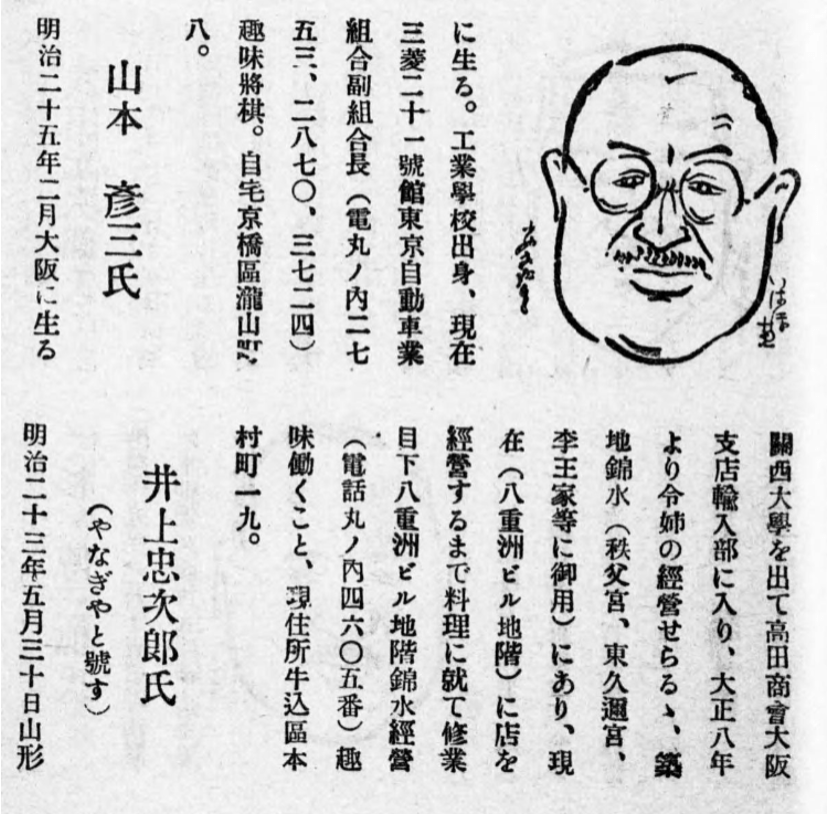

Kinsui Honke is a complicated case. The NDL’s full text search system reveals that there were at least three restaurants with the name “Kinsui” in Tokyo by the end of WWII. The first was a well-known ryōtei in Tsukiji that was mentioned in many celebrity diaries, such as those of Ishibashi Tanzan (1977) and General Baron Honjō Shigeru (Itō et al., 1983). It also served members of the Imperial family. The second was a restaurant located in the basement of the Yaesu Building in Marunouchi. Its owner, Yamamoto Hikosaburō, had previously worked at Tsukiji’s Kinsui, which was managed by his elder sister (Nihon jinji tsūshinsha 1931) (Fig. 1). A directory indicated that Marunouchi’s Kinsui was indeed a branch of Tsukiji’s Kinsui (Kokusai kōronsha 1934). The Kinsui Honke referred to in Matsumoto’s diary was another Kinsui, but a full-text search yielded no results. Fortunately, Matsumoto specified that the Kinsui he visited was in Kōjimachi, Hirakawachō. From the full-text search system, we learned that Marquess Kido Kōichi (1966) and Count Arima Yoriyasu (1995) had stated in their personal accounts that they conducted gatherings at the Kinsui in Hirakawachō. We can therefore conclude that there was a restaurant called “Kinsui” in Hirakawachō, although it is unclear whether it was connected to the other two “Kinsui” restaurants.

Figure 1: Yamamoto Hikosaburō’s Directory Entry.

The three venues at which Matsumoto convened with his colleagues were contiguous with the Imperial Palace. This recalls Roland Barthes’s (1992 [1982]) famous observation that Tokyo was built around the palace, an ‘empty centre.’ It would be therefore worthwhile extracting the locations of ryōtei and teahouses from celebrity personal accounts in order to explore possible connections between their social, economic and personal ties and where they worked, congregated, and resided.

The Future Exploration of the NDL Digital Collection

This series of three articles (see part 1 and part 2) demonstrated the NDL’s full-text search system’s potential in investigating a diverse range of topics in modern Japanese history. These topics encompassed the life and religious beliefs of a middle-ranking technocrat, the financing of SMEs, and the venues for social gatherings in wartime Tokyo. Whilst the full-text search system undoubtedly expedites archival research, it does not permit us to download the OCR text files of the original materials. This means that we cannot perform text extraction on our own devices. This limitation, however, has recently been partially addressed with the release of the ‘Next Digital Library,’ which provides access to the uncorrected OCR text of approximately 280,000 books in the public domain. This new feature offers an alternative way to explore the NDL digital collection and a future topic for digital humanists to pursue.

References

Tsuchida, Hironari 土田宏成 (ed.) (2011). Nikki ni yomu kindai Nihon 4: Shōwa zenki 日記に読む近代日本4:昭和前期. Tōkyō, Yoshikawa kōbunkan

Arima, Yoriyasu 有馬頼寧 (1995). Shintō undō no meian 新党運動の明暗. Kokkai gahō, 37 (8), pp. 44-45.

Barthes, Roland (1992 [1982]). Empire of Signs, trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang.

Gamō, Kansuke 蒲生勘介 (1956). Seiji wa yoru tsukurare-ru 政治は夜つくられる. Tōkyō, Masu shobō.

Higuchi, Hiroshi 樋口弘 (1948). Nippon zaibatsu no kenkyū (1) 日本財閥の研究(一). Tōkyō: Ajitō shōku, 1948).

Higuchi, Kiyoyuki 樋口清之 (1961). Tōkyō no rekishi 東京の歴史. Tōkyō, Yayoi shobō.

Ishibashi, Tanzan 石橋湛山 (1977). Tanzan nikki 湛山日記(4). Jiyū shisō, 5, pp. 41-73.

Itō, Takashi 伊藤隆 et al. (eds.) (1983). Honjō Shigeru nikki: Shōwa 5 nen-Shōwa 8 nen 本庄繁日記 昭和五年~昭和八年. Tōkyō: Yamakawa shuppansha.

Kido, Kōichi 木戸幸一 (1966). Kido Kōichi nikki jōkan 木戸幸一日記 上巻. Tōkyō: Tōkyō daigaku shuppankai.

Kokusai kōronsha 国際公論社 (ed.) (1934). Tōkyō shinshiroku: Shōwa 9-nenban 東京紳士錄 昭和九年版. Tōkyō, Kokusai kōronsha.

Mikuriya, Takashi 御厨貴 (ed.) (2020 [2011]). Kingendai Nihon o shiryō de yomu: “Ōkubo Toshimichi nikki” kara “Tomita memo” made 近現代日本を史料で読む:「大久保利通日記」から「富田メモ」まで. Tōkyō: Chūō kōron shinsha.

Nihon Jinji tsūshinsha 日本人事通信社 (ed.) (1931). Nihon jinjirōku 日本人事録. Tōkyō: Nihon Jinji tsūshinsha.

Ōtsuka, Eisaburō 大塚栄三 (1935). Magoshi Kyōhei ōden 馬越恭平翁伝. Tōkyō: Magoshi Kyōhei ōden hensan-kai.

Shōyu kurabu 尚友俱楽部 et al. (eds.) (2021). Matsumoto Gaku nikki (Shōwa 14 nen-22 nen) 松本学日記 (昭和十四年-二十二年). Tōkyō: Fuyō shobō.

Glossary

Arima Yoriyasu 有馬頼寧

Charyō 茶寮

Dai Nippon Sugar Industry 大日本製糖

Fujiyama Aiichirō 藤山愛一郎

Fujiyama Dōzoku 藤山同族

Funada Naka 船田中

Hachiryū 蜂竜

Hirakawachō 平河町

Honjō Shigeru 本庄繁

Ishibashi Tanzan 石橋湛山

Ishikawa Shingo 石川信吾

Kido Kōichi 本戸幸一

Kinsui 錦水

Kinsui Honke 錦水本家

Kōjimachi 麴町

Kuboi Yoshimichi 窪井義道

Machiai 待合

Magoshi Kyōhei 馬越恭平

Matsumoto Gaku 松本学

Mitsui Bussan 三井物産

Naganuma Kōki 長沼弘毅

Okami 女将

Ryōtei 料亭

Shimbashi 新橋

Sugar Industry Hall 糖業会館

Teahouse politics 待合政治

Tsukiji 築地

Yaesu Building 八重洲ビル

Yamamoto Hikosaburō 山本三彦

Yūrakuchō 有楽町

2 thoughts on “Unearthing Modern Japan’s Subterranean Networks with the National Diet Library’s (NDL) Full-Text Search System (Part 3): Celebrity Diaries and Spatial Politics in Wartime Tokyo”