This contribution is based on a presentation given at The Digital Orientalist’s Virtual Conference 2025 (AI and the Digital Humanities) by Enes Yılandiloğlu (University of Helsinki).

Introduction and Background[1]

Scholars have provided various perspectives on how Europe historically perceived the Orient[2], such as Said (1978) with his ground-breaking work Orientalism, as well as Ballaster (2005) and Osterhammel (2018). Moreover, despite this enormous literature on Orientalism, most studies remain limited to specific, well-known texts such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (Baktır 2014; Lowe 1991). Additionally, while these studies analyzed what British perception of the Orient in the eighteenth-century British travel writing via qualitative and discursive approaches, they lack computational and large-scale analysis using data-driven methods on in which locations British understanding of the Orient was shaped. This paper addresses that gap by applying computational techniques such as automatically detecting the locations in the text and visualizing hundreds of locations on a map. Thus, it scales the analysis to detect geographical macro-patterns in the travel narratives.

As indicated by Bodenhamer (2015), while establishing the methodological framework, this study engages with the idea of deep mapping, integrating GIS with narrative, memory, and emotion to form multi-layered representations of place that traditional maps cannot provide. Following the work of Ethington and Toyosawa (2015, 73), rather than treating maps as static backgrounds, this study also contextualizes maps to convey the narrative history of places. Therefore, mapping travel writing becomes a task to visualize the collective voice of the eighteenth-century British travel writing on the Orient, regardless of who the authors are and how important they are.

Data and Methods

The dataset consists of 355 OCR’d English travel writings published between 1700 and 1800, from the Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). The temporal imbalance it has the low number of titles in the first decades compared to the last ones, inherent in large, digitized archives, suggests that big data does not necessarily mean balanced data (Edmond and Folan 2017; Tüfekçi 2014). The texts were linked with bibliographic metadata from the Eighteenth Century Short Title Catalogue (ESTC). The enriched version of the ESTC, which provides publication year, genre, and author information, and gender, was leveraged in this study. OCR errors in ECCO texts were automatically corrected by Kanerva et al (2025). For geocoding, Pleiades (Elliott et al. 2016) was used as a gazetteer providing over 44,000 historical place records for mainly the regions around the Mediterranean.

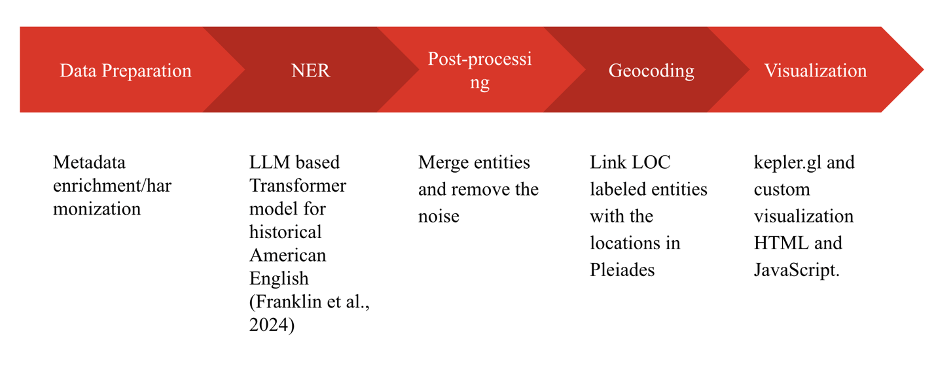

The method stands out as an end-to-end automated pipeline; in other words, from finding location entities to visualization, everything is performed automatically without human intervention, yet manual analysis is still required at the end. It consists of four main steps: data preparation, NER and postprocessing, geocoding, and lastly visualization. Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end pipeline.

Fig. 1. The end-to-end computational pipeline.

For NER analysis, the model dell-research-harvard/historical_newspaper_ner was deployed. It was selected as the most suitable because it is the only open-source NER model that was trained on OCR’d historical English data (historical American newspapers). After the NER, ambiguous cases from toponymic homonymy were resolved using two heuristics. First, when one candidate location was in the Orient and another was not, if the majority of the five nearest unambiguous location entities were in the Orient according to Pleiades, entities were included. Second, for toponyms where all candidates were in the Orient (e.g., Alexandria), the candidate geographically closest to the majority of the five nearest unambiguous entities was chosen. At the end of this process, over 40,000 entities were linked to entries in Pleiades located in the Orient, between 12–42° N and 25–65° E.

Results and Discussion

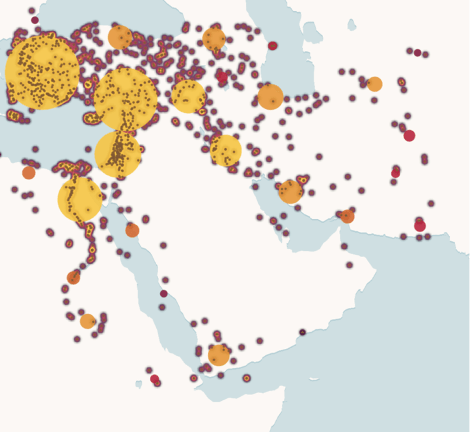

The results present a broad view of references to the Orient. Figure 2 displays a snippet of an exemplary map with various results, uncovering various macro-patterns. In Figure 2, a heatmap function is utilized in addition to the density clusters with big circles, ranging from yellow to red depending on the size of the cluster.

Fig. 2. The map for the mentions.

The first macro-pattern is the high concentration of the Orient-related mentions along coastal regions, aligning with the notion of Blue Humanities. As Gillis argues, maritime spaces are a significant element that shape human lives (Gillis 2013). This is echoed in Figure 2 since maritime centers such as Cyprus, Constantinople, Antioch, and Smyrna attracted a significant number of mentions. On the other hand, the aforementioned places, in addition to Aleppo, Baghdad, Damascus, and Jerusalem, were also contemporary trade centers, as discussed by Davis and Mather (Davis 2012; Mather 2009). This pattern confirms the impact of trade on British travel writing. Lastly, the imbalanced distribution of the mentions across regions, such as density around the Nile corridor and Jerusalem as opposed to the underrepresentation of Persia, signifies an important fact: even though a travel writing claims to be about travel to the Orient, it is, in reality, only about a fraction of the Orient. Hence, while the analyses conducted by Ballaster (2005), Lowe (1991), and others (for example Sakhnini 2021) have illuminated how British authors perceived the Orient, they do not particularly analyze which parts of the Orient such perceptions were based on. This study answers this question by mapping 355 travel writings.

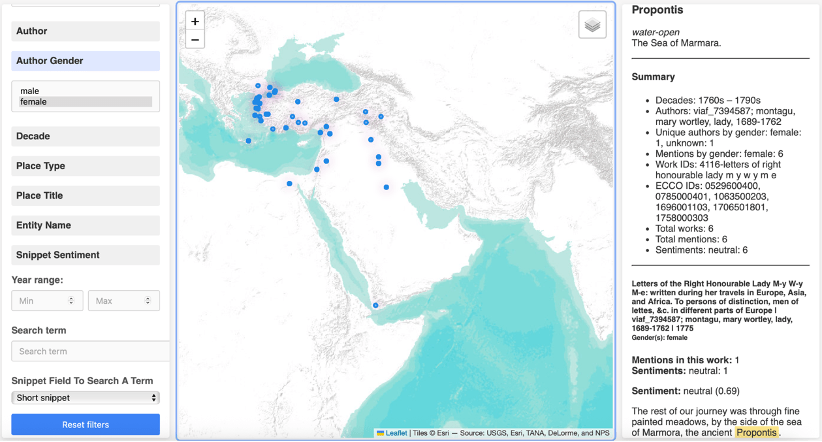

The current efforts aim to present the data on a deep map. A preliminary deep map can be observed in Figure 3, where users can see the map in the center, filtering and layer options on the left, and a description of the selected location with a statistical summary and snippets title by title on the right side. The current layers, including base points, density heatmaps, density clusters, and temporal filters, enable users to trace changes toward specific places over time or by other variables such as gender. Converting the textual data into a deep map enables researchers to analyze how a certain location was mentioned throughout time, how an author wrote, and so on. Yet, it is important to remember that visualizations are interpretive constructions rather than objective representations (Drucker 2020, 102).

Fig. 3. A preliminary deep map.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how computational methods can enrich the study of eighteenth-century British travel writing by enabling large-scale, data-driven spatial analysis. Methodologically, NER and GIS provide a scalable and reproducible framework. The same approach could be extended to other corpora and regions, such as Italian Grand Tour accounts. Analyzing over 40,000 location entities from 355 titles, provides valuable insight into eighteenth-century British travel writing on the Orient, not feasible without computational methods. The clusters around coastal and trade centers demonstrate the connection among geography, commerce, and travel writing. Future work will aim to improve the visualization interface and expand the dataset with the Early English Books Online to cover the seventeenth century as well.

Notes

[1] This work presents the preliminary results from the author’s Master thesis (Yılandiloğlu 2025).

[2] Orient refers the area, centered on the eastern Mediterranean, from Asia Minor to Persia, from Caucasia to Yemen in this study.

References

Baktır, Hasan. The Representation of the Ottoman Orient in Eighteenth-Century English Literature: Ottoman Society and Culture in Pseudo-Oriental Letters, Oriental Tales and Travel Literature. Stuttgart: Ibidem Verlag, 2014.

Ballaster, Rosalind. Fabulous Orients: Fictions of the East in England, 1662–1785. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Bodenhamer, David J., John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, eds. Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015.

Davis, Ralph. The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012.

Drucker, Johanna. Visualization and Interpretation: Humanistic Approaches to Display. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020.

Edmond, Jennifer, and Georgina Nugent Folan. “Digitising Cultural Complexity: Representing Rich Cultural Data in a Big Data Environment.” arXiv preprint (2017).

Elliott, Tom, Brian Turner, and Sean Gillies. Pleiades: A Gazetteer of Past Places [data set]. 2016. https://pleiades.stoa.org/.

Ethington, Philip J., and Nobuko Toyosawa. “Inscribing the Past: Depth as Narrative in Historical Spacetime.” In Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives, edited by Mei-Po K. Yuan, Barney Warf, Nobuko Toyosawa, Paul Rayson, John McIntosh, W. Martin Martin, and David J. Bodenhamer, 72–101. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/49063.

Franklin, Ben, et al. “News Déjà Vu: Connecting Past and Present with Semantic Search.” arXiv preprint (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.15593.

Gillis, John R. “The Blue Humanities.” Humanities 34, no. 3 (2013): 10-13.

Kanerva, Jenna, Cassandra Ledins, Siiri Käpyaho, and Filip Ginter. “OCR Error Post-Correction with LLMs in Historical Documents: No Free Lunches.” In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Resources and Representations for Under-Resourced Languages and Domains (RESOURCEFUL-2025), edited by Špela Arhar Holdt, Nikolai Ilinykh, Barbara Scalvini, Micaella Bruton, Iben Nyholm Debess, and Crina Madalina Tudor, 38–47. Tallinn, Estonia: University of Tartu Library, 2025. https://aclanthology.org/2025.resourceful-1.8/

Lowe, Lisa. Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Mather, James. Pashas: Traders and Travellers in the Islamic World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

Osterhammel, Jürgen. Unfabling the East: The Enlightenment’s Encounter with Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Sakhnini, Mohammad. “Improving Experiences: Eighteenth-Century European Encounters with Arabs.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 43, no. 1 (2021): 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2021.1997954.

Tolonen, Mikko, Eetu Mäkelä, and Leo Lahti. “The Anatomy of Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).” Eighteenth-Century Studies 56, no. 1 (2022): 95–123.

Tufekci, Zeynep. “Big Questions for Social Media Big Data: Representativeness, Validity and Other Methodological Pitfalls.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 8, no. 1 (2014): 505–514. Palo Alto, CA: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14517.

Yılandiloğlu, Enes. Mapping Orientalism: A Quantitative Study of Eighteenth-Century British Travel Writing. Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki, 2025. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/602337.

Yılandiloğlu, Enes. “Mapping Orientalism: A Quantitative Study of Eighteenth-Century British Travel Writing.” Zenodo, July 9, 2025. 82 pages. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15847201.

Yuan, Miao, John McIntosh, and Grant DeLozier. “GIS as a Narrative Generation Platform.” In Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives, edited by David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, 176–202. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015.

2 thoughts on “Mapping Eighteenth-Century British Travel Writing on the Orient”