This is a post by contributing writer, Emma Donington-Kiey, an independent researcher and MA graduate of Interdisciplinary Japanese Studies from the University of East Anglia and the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture (SISJAC), UK.

Just as sartorial Japonisme is the blend of Japanese aesthetics and fashion, research into the topic benefits from a combination of both traditional archive research and new digital tools. Consulting digital archives has become a standard practice for any object-based research. For my master’s dissertation, I wanted to examine how Japonisme-inspired garments from late nineteenth century Europe were perceived, and later acquired and exhibited by major costume collections across the world. As it was still during COVID restrictions, my research became confined to what I could access digitally, and thus my focus on the digital archives of two leading costume collections came about.

I was most interested in the beautiful Japonisme-inspired collection at the Kyoto Costume Institute (KCI), a Japanese fashion museum of historical Western clothing. During my research I was browsing an exhibition catalogue for the Brooklyn Museum’s Opulent Eras: Worth, Doucet and Pignat (1990) where the design houses included are considered leading figures in the early popularity of Japanese motifs and aesthetics in fashion, and just by chance came across a House of Worth ball gown dated to 1887 now housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute (CI) (see figure 1 – you can also view the original archive entry here). Of course, this is not shocking to find in an exhibition on Worth and his couturier peers; however, it came as a surprise to me after I had seen an evening gown in the KCI’s digital archive that closely resembled many of its features (see figure 2 – you can view the original archive entry here). While these are not identical, they are dresses from the same House of Worth collection and the design they share on the skirt has been attributed by both costume institute’s as evidence of Japonisme in fashion – most prominently being the asymmetrical cloud and sunbeam pattern.

Fig 1. Part of the digital archive entry for Ball gown by designer Charles Frederick Worth (ca.1887), Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Online Collection. 49.3.28a, b.

This led me to a deep-dive into what I could learn from collections of sartorial Japonisme in museums today whilst considering themes of cultural identity, digital museum practice, and the history of Japonisme in haute couture. At the heart of this would be a close comparison of two digital archives with similar objects and their individual archive entries. I was interested in how a digital platform can be used to demonstrate the blurring of cultural boundaries inherent in a garment that was a product of cross-cultural encounter. On reflection, this initial research can be used as the beginning for a much larger digital humanities project which could bring together many different types of costume collections relating to Japonisme – both well known and currently obscured. The next section will propose some directions this type of project could take.

Fig 2. Digital archive entry for Evening Dress by Charles Frederick Worth (c.1894), Kyoto Costume Institute, Digital Archive. AC4799 84-9-2AB.

1. Comparing Digital Archives

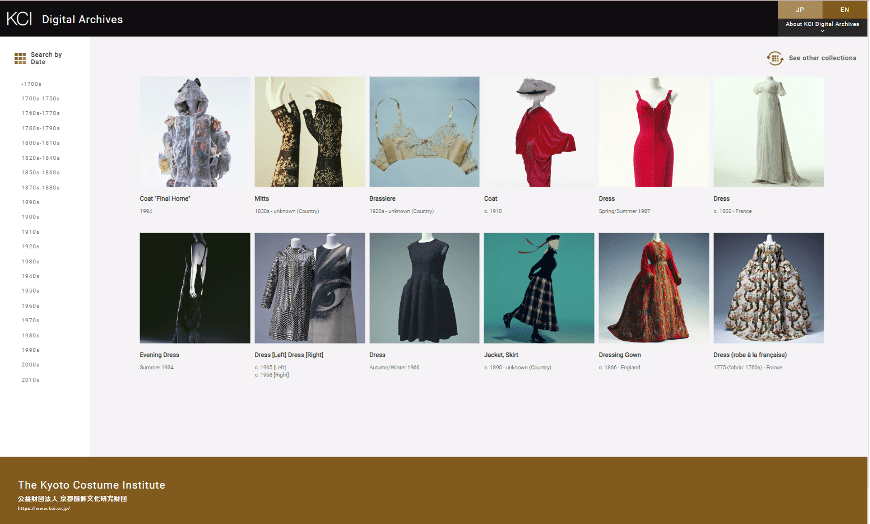

The KCI and the CI were some of the first costume collections to offer a publicly-accessible digital archive; the KCI launched an early version of its Digital Archives around 2007, and the Met offered access to its collection (including the CI) online in some capacity in 2000, with a public searchable database of its entire collection, including the CI, launched around 2009, a breakthrough for collection-based research.[1] The KCI does not provide a way to search other than by decade(s), laid out in a chronological timeline going down the left of the screen (see figure 3). By comparison, the Met’s digital collection includes an “advanced collection search” that can be searched or filtered through by Object type/material, Geographic Location, Date/Era, and Department (see figure 4). Both are useful for different types of research, with the KCI offering a constant visual timeline of Western dress history from c.1700-2010s, but not facilitating a quick search for a historian doing specific object analysis quite like the Met does.

Fig. 3. Homepage of the KCI Digital Archives showing a random selection of garments in their collection and the decades on the left that the user can search by.

There are other aspects that I compared in my dissertation such as differences in metadata attributes and how this shapes a user’s perception when conducting object-based research. For instance, the Met’s archive entry includes the information that the House of Worth is a French design house, and that Charles Frederick Worth was “French, born England,” giving geographic and contextual background to the object. The Met also provides provenance for the gown, stating “Gift of Orme Wilson and R. Thornton Wilson, in memory of their mother, Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor Wilson, 1949” under the Credit Line attribute. This information could in itself inspire a new line of enquiry. On the other hand, the KCI refers to simply “the West” in the corresponding entry description for its geographic origin and provides no provenance or acquisition record. This presents the garment as more culturally ambiguous, and more flexible in the user’s geographical imagination. There are many other factors to consider including image choice and the corresponding digitisation practice, supplementary information provided or simple user usability which I do not have the space for here, but there are other examples I can recommend that refer to Japanese collections specifically.[2]

Fig. 4. Homepage of the Met’s online collection with the various filters and search specifications, it also shows a random selection of garments in their collection.

2. Mapping Sartorial Japonisme

By going beyond this and creating a shared database of international sartorial Japonisme collections, this approach could be expanded upon tenfold. Collated databases are nothing new in the Japanese studies and Fashion studies world. In fashion history, there are several well known resources including Fashion and Race Database, Fashioning the Self and the Chronicle Archive of Tokyo Street Fashion (CAT STREET) which are all fashion-based digital humanities projects designed to bridge fashion collections and their stories through time. Faith Cooper launched a project with similar sentiments in 2020 entitled the Asian Fashion Archive. Her website provides a useful jumping-off point for students, scholars or the public, collating museums, film and photography, educational resources and more, all on the topic of Asian fashion and its history.

Sam Huckerby’s project Piece by Piece is a wonderful example of using ArcGIS StoryMaps and text mining to collate the stories of dress history in nineteenth century Britain by connecting garments with the history of the materials they are made from. Similarly, text mining tools such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) have been used by fashion studies researchers in tracing the history of or forecasting future fashion trends.[3] In the case of Japonisme, common visual motifs, such as clouds, chrysanthemums, cranes or lilies could also be made searchable using software like Google Lens. While not perfect, I was able to consistently use it on an image of the Met gown to identify the similar KCI gown in under ten suggestions, as well as others of a similar date, style or colour (try it for yourself!). Both costume institutes have worked with Google in the past, contributing to the Google Arts and Culture initiative. “Japonism in Fashion” is one of the compilation of objects they have created, with images from the KCI and CI taking centre stage. You can also search by institution and look at 360° images of previous exhibitions and some objects on display (for example, this Rei Kawakubo exhibition “Art of the In-between” from 2017). This initiative is user-friendly, and could easily be expanded upon to facilitate more academic-focused object-based study, and even bring virtual reality and 3D digitisation into the mix.

Incorporating text and visual-based recognition software would facilitate more efficient research such as the identification of common keywords, themes or visual descriptions, especially if sartorial Japonisme collections could be mapped on a shared database. I think that this could also help to disseminate ideas and advice on future museum practice and collaboration between different professionals at different Japonisme-inspired collections at various stages of digital curation. In Professor Arisa Yamaguchi’s recent book, Sartorial Japonisme and the Experience of Kimonos in Britain, 1865-1914, she highlights local museums across the UK with impressive kimono collections. She found that some were significantly under-researched, and part of that is due to online accessibility and visibility. A shared database could change the way different users – professional, academic and public – engaged with smaller collections.

One of the reasons I was compelled to return to this topic in an article for the DO was because of the Met’s new exhibition and theme for the Met Gala 2024, Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion running from May 10th – September 16th 2024. This exhibition showcases the ephemerality of historical garments and the need to develop new techniques if we are to continue exhibiting them. The 1887 Worth evening gown from the CI collection will be displayed among 250 other garments and accessories. The gown has been deemed too fragile to be placed on a mannequin and will be displayed flat, with visitor engagement being enhanced by the use of various technologies to enhance the exhibition experience such as animations, soundscapes and augmented reality.

The inclusion of sartorial Japonisme examples in this exhibition demonstrates the importance of this topic to the study of fashion history, and also the role these two institutes play in preserving and making accessible these garments for future study, and hopefully adopting new and exciting techniques to do so.

This article is by no means an exhaustive list and I would love to continue compiling other potential digital methods for sartorial research!

References

[1] Sauro, Clare. “Digitized Historic Costume Collections: Inspiring The Future While Preserving The Past”. Journal Of The American Society For Information Science And Technology 60, no. 9 (2009): 1939-1941. doi:10.1002/asi.21137, p.1940.

[2] Bincsik, Monika, Shinya Maezaki, and Kenji Hattori. “Digital Archive Project to Catalogue Exported Japanese Decorative Arts.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 6, 1–2 (2012): 42–56. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2012.0037

[3] An, Hyosun, and Minjung Park. Approaching Fashion Design Trend Applications Using Text Mining and Semantic Network Analysis. Fashion and Textiles 7, 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-020-00221-w.

One thought on “The Future of Researching Sartorial Japonisme: Using Digital Archives and Other Helpful Tools”