In recent years, visual studies have gained significance in digital humanities due to advancements in processing visual materials at scale, notably propelled by the progress in neural networks for computer vision, where interconnected artificial neurons learn to perform tasks by adjusting their connections based on data inspired by how human brain works. This surge is facilitated by accessible GPUs (graphics processing units) for personal computers and vibrant open-source communities, enabling digital humanists to explore computer vision. This article introduces the application of object detection, exemplified by my project, “Flowers Now and Then: Floral Pattern Detection on Historical Chinese Papercuts with Contemporary Datasets.” In this initiative, I trained the computer using contemporary Chinese papercuts from the Internet, employing it to identify specific patterns in historical papercuts.

Object detection refers to the ability of a trained computer to identify specific objects within a visual source, for example, to tell a peach pattern from a porcelain plate or to recognize a bat image embroidered onto a jacket. In simple terms, the process through which a computer learns to detect a particular visual pattern mirrors the human learning experience, encompassing two essential steps. During the initial step, the computer is presented with dozens and hundreds of images depicting a specific object, enabling it to grasp the distinctive features of the designated item. Subsequently, in the second step, the computer employs its learned knowledge to identify the object within new images. The current visual studies largely rely on the translation of visual elements to text, associating textual descriptions as tags and metadata with visual materials. In object detection, in contrast, computers undergo direct learning from image examination, transforming the conventional image-to-text system into a more direct image-to-image interaction. Object detection in digital humanities was demonstrated in 2021 by a Belgian team, who annotated images from museum and online collections and created the dataset MINERVA for the detection of musical instruments in visual arts1.

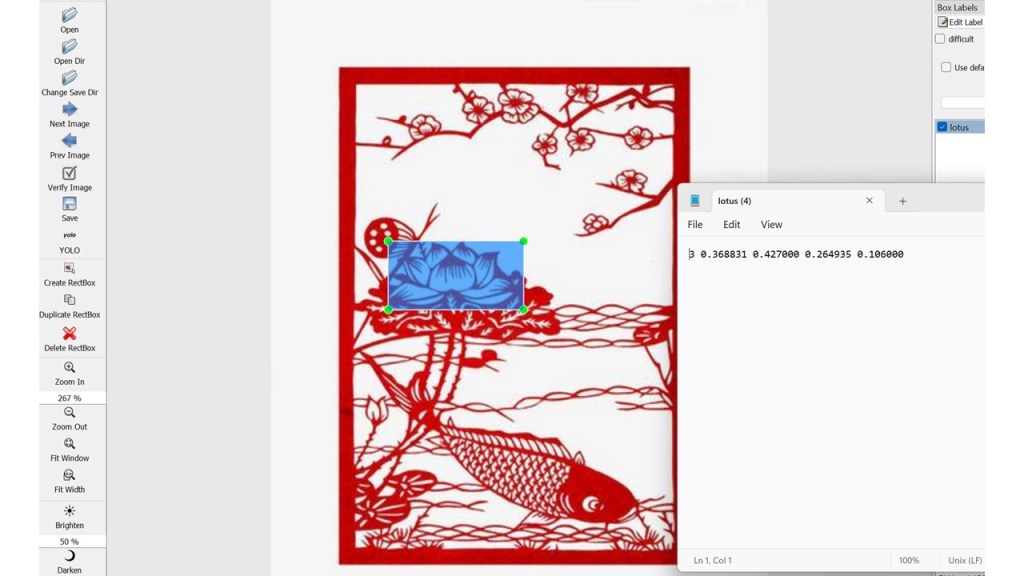

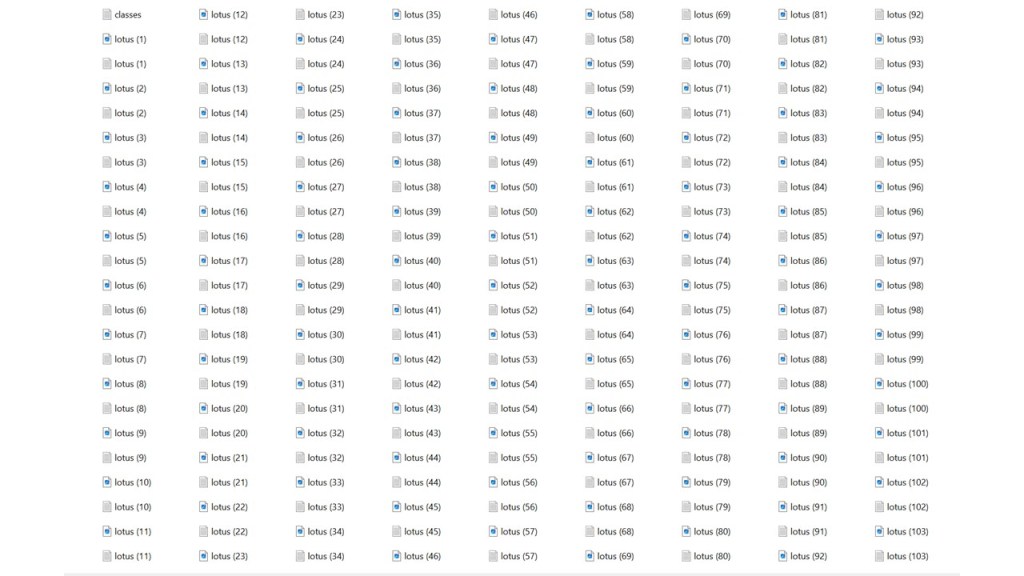

My project relies on two open-source resources, LabelIMG and YOLOv8. LabelIMG is employed in the preliminary stage for image annotation. During image annotation, the designated item in each image needs to be manually marked, and this creates coordinates for the computer to identify the location of the item in an image. In my project, I collected contemporary papercuts from the Internet and annotated them in LabelIMG. Figure 1 indicates that when a rectangular box was created to identify the item “lotus” in an image, coordinates were automatically generated by LabelIMG in an associated txt file. After processing dozens or hundreds of images with the same annotation process, a dataset was created for the computer to learn what a “lotus” looks like (figure 2). This stage provided essential data for the following training step.

Figure 1. LabelIMG interface: the rectangle box that identifies a lotus pattern in a papercut artwork. The txt file: coordinates created for the rectangle box.

Figure 2. Part of the dataset that includes both images of contemporary lotus papercuts and their associated annotations.

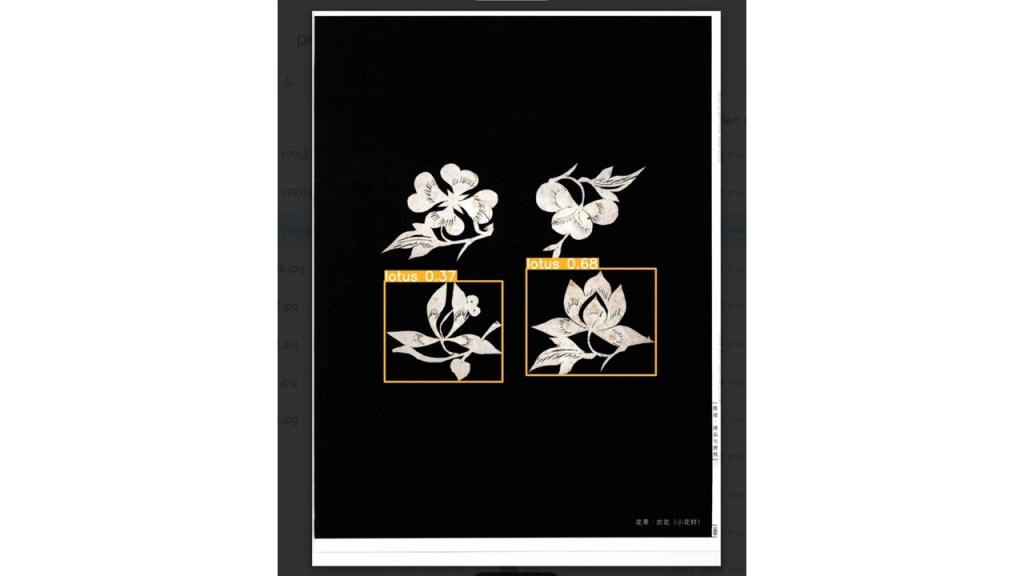

YOLO (You Only Look Once) is a popular object detection algorithm that harnesses the power of neural networks and efficiently processes images. YOLO is widely used to identify common objects, such as vehicles, human figures, and animals in a real-world environment. By utilizing visual art materials, my project tests the capability of YOLOv8 (the latest version launched in early 2023) in a two-dimensional environment. In my project, the dataset prepared for “lotus” was uploaded to build a custom model. Then, I instructed YOLOv8 to detect lotus in given images. YOLOv8 would generate a “confidence score” for each lotus identified. Figure 3 demonstrates that YOLOv8 has identified two lotus patterns from an image belonged to the historical jinbaozhai 進寶齋 papercut collection and marked them with rectangle boxes2. The number “0.68” indicates that YOLOv8 is 68 percent confident with this detection result. Confidence score is affected by various factors including the quality, quantity, and variations of the training dataset, the selected training model (YOLOv8 offers five different training models in various sizes ranging from nano to extra large), the quality of images to be predicted, and more, which allow for explorations of relations between training images and detected images. In my project, by detecting floral images in historical papercuts with a custom model built on contemporary papercuts, I asked the relationship between contemporary and historical popular patterns in papercuts.

Figure 3. Two lotus patterns are detected from the jinbaozhai papercut collection.

In conclusion, this article has introduced the basic concepts of object detection and its potential application in studying Chinese popular visual arts. Direct image-to-image comparisons make it possible to explore new research questions, bring new perspectives, and insights. Since YOLO is designed for real-world objects, its accuracy rate in detecting visual art materials is relatively low. However, the technology of object detection is still under heavy development, and its potential in the humanities awaits to be discovered.

Endnotes:

1. Matthia Sabatelli, Nikolay Banar, Marie Cocriamont, Eva Coudyzer, Karine Lasaracina, Walter Daelemans, Pierre Geurts, and Mike Kestemont, “Advances in Digital Music Iconography: Benchmarking the Detection of Musical Instruments in Unrestricted, Non-Photorealistic Images from the Artistic Domain,” Digital Humanities Quarterly Vol. 15, (1), 2021. https://dhq-static.digitalhumanities.org/pdf/000517.pdf

2. Feng Jicai 馮驥才edited, Xiaoshi de huayang: Jinbao zhai Yin Deyuan jianzhi 消逝的花樣——進寶齋尹德元剪紙 (Embroidery Patterns that Faded Away: Yin Deyuan Papercuts from Jinbao Zhai). (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2009), 89.

References:

Feng Jicai 馮驥才edited. Xiaoshi de huayang: Jinbao zhai Yin Deyuan jianzhi 消逝的花樣——進寶齋尹德元剪紙 (Embroidery Patterns that Faded Away: Yin Deyuan Papercuts from Jinbao Zhai). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2009.

Sabatelli, Matthia, Nikolay Banar, Marie Cocriamont, Eva Coudyzer, Karine Lasaracina, Walter Daelemans, Pierre Geurts, and Mike Kestemont. “Advances in Digital Music Iconography: Benchmarking the Detection of Musical Instruments in Unrestricted, Non-Photorealistic Images from the Artistic Domain.” Digital Humanities Quarterly Vol. 15, (1), 2021. https://dhq-static.digitalhumanities.org/pdf/000517.pdf

This is so cool!