Introduction

Known for his speed of transcribing, Maʿrūf Baghdādī was one of the most prominent calligraphers of 14th– and 15th-century Iran. Our understanding about his life and career is confined to the limited information provided by historical and art-historical sources that refer to him in regard to his legendary penmanship. However, despite the accounts about his unique copying skills, not many manuscripts in his hand have come down to us. His few signed works include a copy of the Khamsa of Niẓāmī (British Library, Or. 13802), an anthology of poetry known as Jung-i Maʿrūf Baghdādī (Golestan Palace Library, no. 2184), and Ḥāfiẓ Abrū’s chronicle, the Kulliyyāt-i Tārīkhī (Topkapi Palace Library, B. 282).

With the expansion of digitised resources of libraries and collections, it is more feasible now to identify unexplored objects and to gather a more comprehensive portfolio of scribes, artists and craftsmen. In the case of Maʿrūf, having access to publicly shared online images played a pivotal role in distinguishing one of his unsigned works that had not been previously identified. This short article attempts to present an abridged description of Maʿrūf’s career based on the extant, sporadic information about him in primary sources before discussing his signed manuscripts. I will then introduce a previously neglected work in his hand from Iskandar Sultan’s Miscellany at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (13.228.19).

Maʿrūf Baghdādī

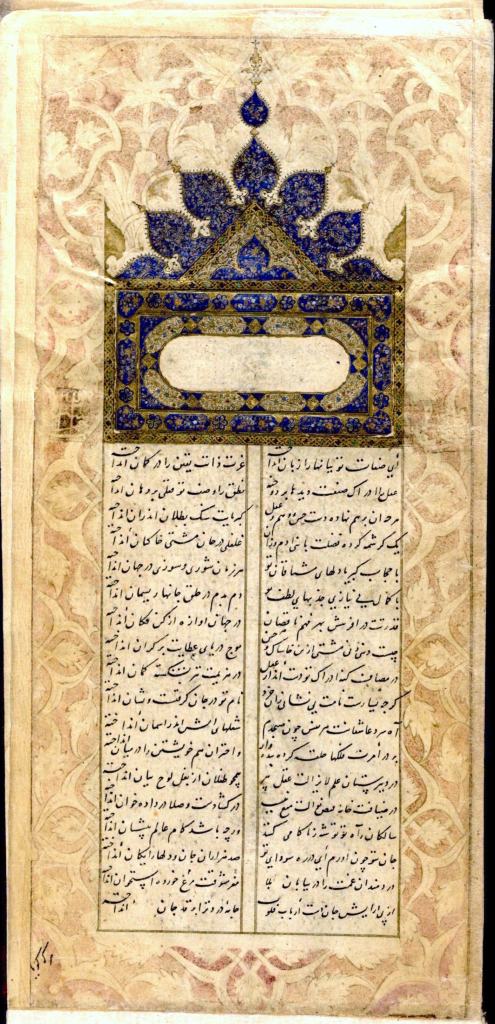

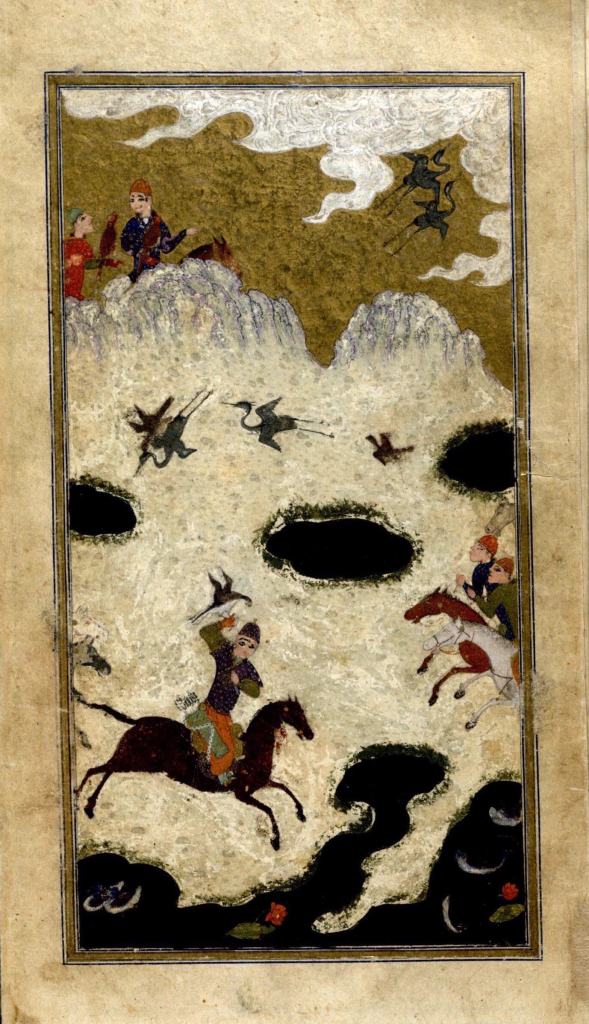

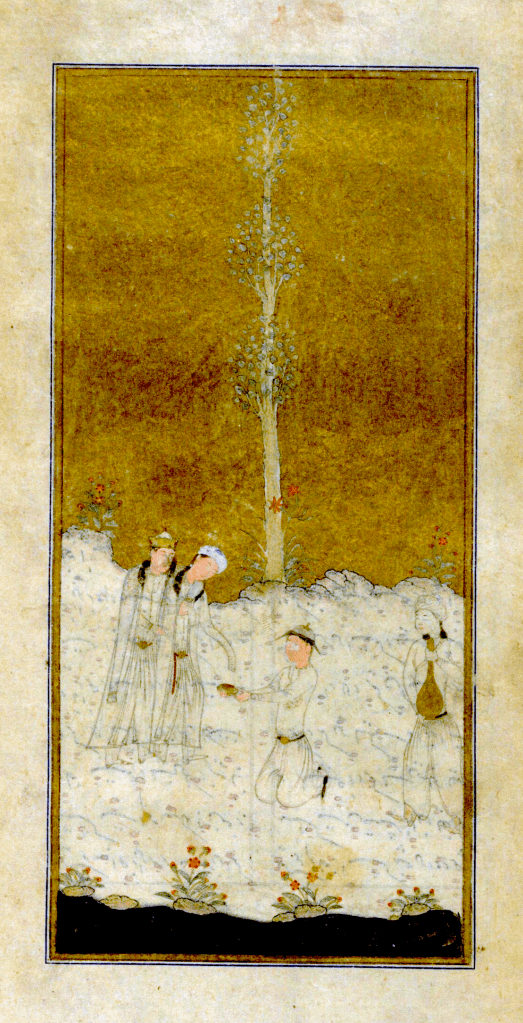

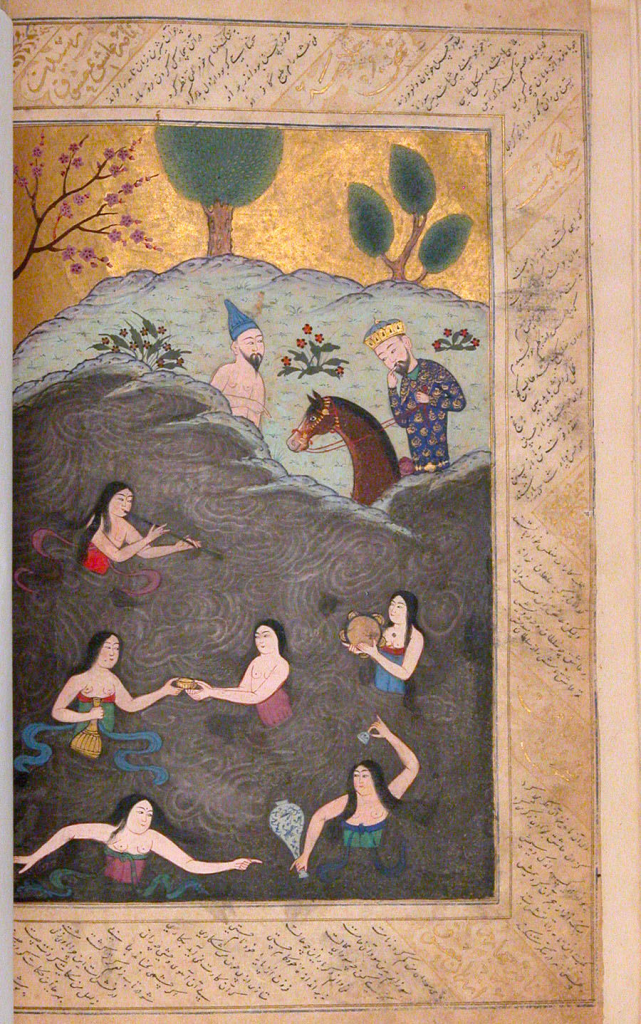

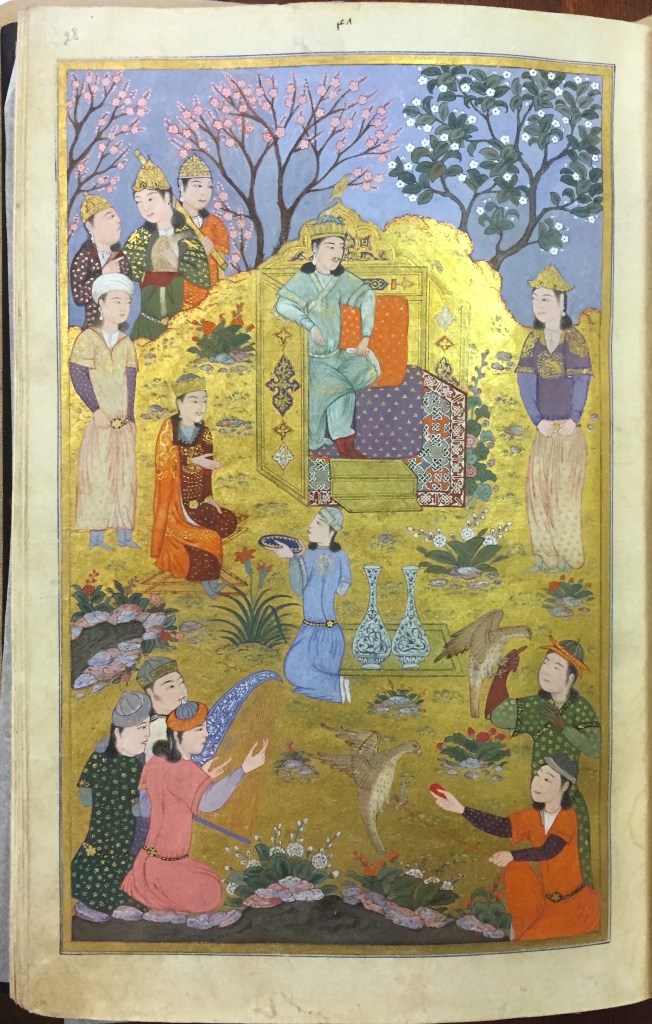

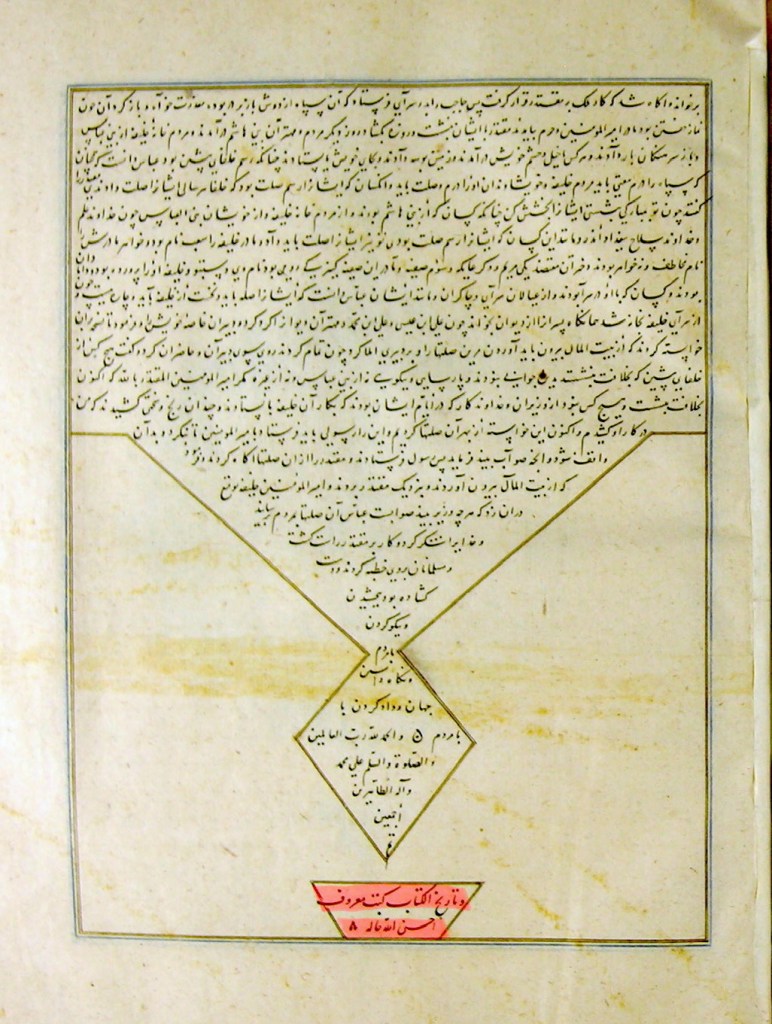

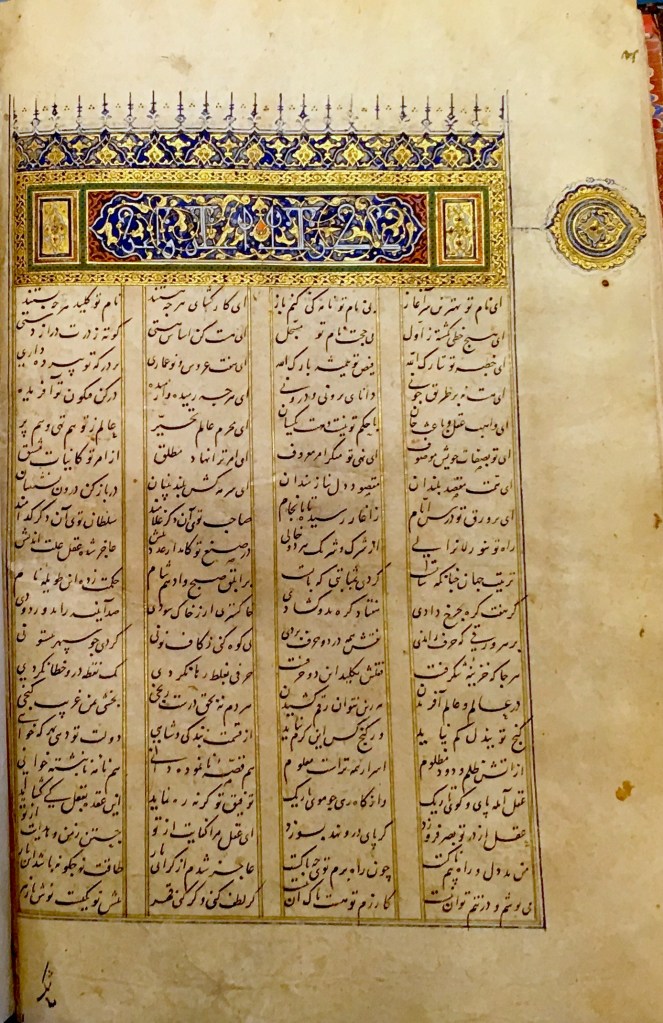

Maʿrūf Baghdādī was born in the second half of the 14th century in Baghdad and joined the Jalayirid court in his youth. He began his professional career as a scribe at the court of Sultan Husayn (r. 1376-1382) in Tabriz, and kept his position under the ruler’s brother, Sultan Aḥmad (r. 1382-1410).1 Maʿrūf’s oldest work is an undated anthology of Persian poetry, containing twelve illuminated pages in Shirazi style, five illustrations and decorated margins (fig. 1), known as Jung (Anthology) of Maʿrūf Baghdādī. It was compiled for Sultan Aḥmad and includes a few of his poems in addition to other poetry by some great poets, such as Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī. It is now housed in the Tehran Golestan Palace, MS no. 2184 (fig. 2-3).2

The Patrons

In 1393, Timur (Tamerlane) conquered Baghdad, and Sultan Aḥmad, who fled to Egypt, was imprisoned by the Mamluks. After being set free, his conflicts with Qara Yusuf resulted in him being captured and executed in 1410. After Sultan Aḥmad was defeated by the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid (r. 1389-1402) in 1401, Maʿrūf left his service and joined the court of his son-in-law Iskandar Sultan grandson of Timur (1384-1414) and continued to work for him until the prince’s demise. As the head of Iskandar’s royal workshop in Shiraz, he was responsible for transcribing 100 verses per day – almost twice the average work-rate of a Timurid scribe. Most primary accounts of Maʿrūf provide a narrative of him postponing copying for a fortnight and, when being asked the reason, he expressed that he wished to copy 1500 verses in a day! Amazed at such a claim, the prince commanded it to take place in the city’s main square in Isfahan, and the scribe wrote 1500 verses in neat hand from dawn to dusk while people had gathered to watch that marvel.

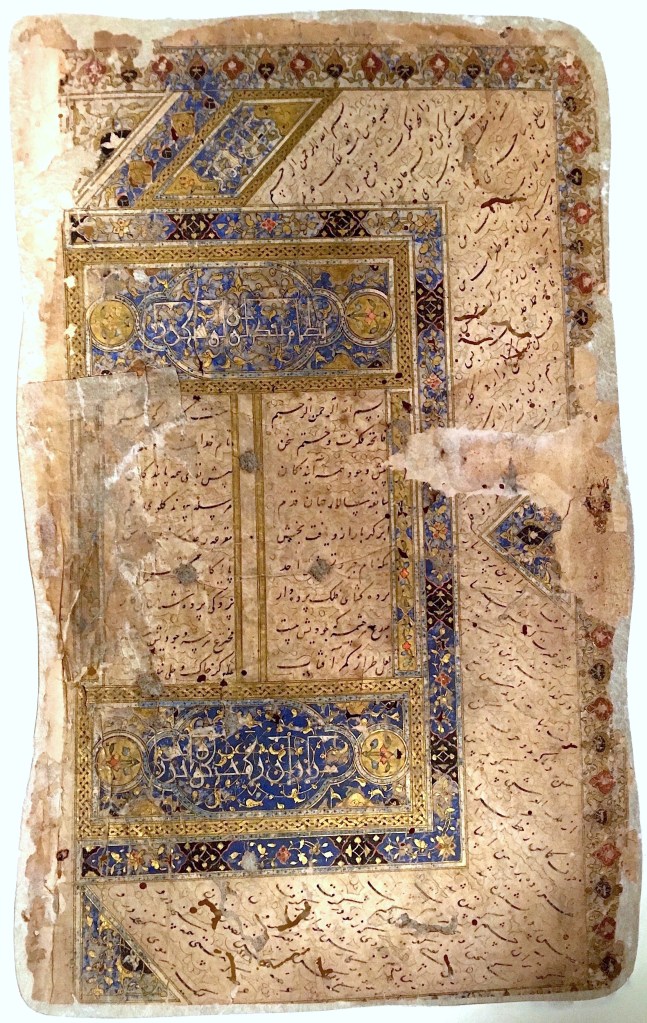

With such fame and incredible skills, it is not surprising that Maʿrūf was among the treasures Shahrukh b. Timur took as booty and sent to his capital Herat after his nephew’s death. The king appointed Maʿrūf as scribe at his royal library right afterwards. There he copied the Kulliyyāt-i Tārīkhī composed by the Timurid court historian Ḥāfiẓ Abrū; a manuscript with 20 illustrations. This copy is signed (in f. 297v), dated 818AH (1415) – one year after Iskandar’s death – and dedicated to Shahrukh (fig. 4). It is now located in the Topkapi Palace Library (MS B. 282).

Living in Herat at the vicinity of the court and library of Shahrukh’s bibliophile son Prince Bāysunghur (1397-1433), Maʿrūf was a strong candidate to supervise the prince’s celebrated library-atelier, soon after it was established, but we know that he was not elected. Historical accounts, on the other hand, report a fateful incident that caused inauspicious consequences to the scribe.

Following an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Shahrukh, the attacker was killed immediately, before his identity was recognised. Tracing him and his association with Hurufism, it was revealed that his name was Aḥmad Lur and that Maʿrūf was acquainted with the assassin. The reports agree that since Maʿrūf had not previously followed Bāysunghur’s command to copy the Khamsa of Niẓāmī for him, and as the prince had held grudges, this was the best time for Bāysunghur to take revenge by sending the scribe to the gallows a few times before imprisoning him in the Ikhtiyār al-Dīn fortress until his death in 1427.3

Although this historical account has been reiterated and considered valid by many scholars, the presence of a Khamsa in Maʿrūf’s hand dating to 1421 calls us to revisit the accuracy of the narrative. This manuscript contains the complete Khamsa of Niẓāmī in the main text area, signed (in f. 794r) Maʿrūf ibn ʿAbdullāh al-Baghdādī, 824AH, Herat; along with the Khamsa of Amīr Khusrau Dihlavī and the Dah-nāma of Ibn ʿImād in the margins, in the hand of Ḥusayn b. Miyānjī Khāksār in 838AH (fig. 5).4 It contains 17 illustrations and beautiful illuminations, and is kept at the British Library (MS Or. 13802) in London. Even though it is not explicitly dedicated to the prince, of the two patrons in Herat, Shāhrukh was mainly interested in historical works, while Bāysunghur was not only known for his passion for poetry, but also for his interest in the Khamsa of Niẓāmī, according to various contemporary accounts. The prince had commissioned another complete Khamsa a year earlier (British Library, Or. 12087, signed Jaʿfar al-Ḥāfiẓ) (fig. 6), and a copy of the Khusrau u Shirin of Niẓāmī (Institute of Oriental studies, St. Petersburg, MS B-132) in the same year; both penned by Jaʿfar Tabrīzī who received the princely sobriquet Bāysunghurī the very same year (1421) and became head of the royal library-atelier.5

The three above-mentioned manuscripts are the only known works copied by the scribe. Curiously, there has been nothing in his hand from the period he was at the service of Prince Iskandar, for which we have numerous accounts in primary sources highlighting his legendary copying speed. This could only point out to our lack of knowledge about those works written by him, waiting yet to be discovered.

An Unsigned Work by Maʿrūf

Since Maʿrūf Baghdādī was one of the pioneers of early nastaʿliq script, I had frequently examined his calligraphic style and character of his hand over the years and was familiar with his calligraphy. The digital images of the Anthology of Poetry commissioned by Iskandar sultan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MS 13.228.19) enticed my curiosity to investigate whether it was indeed copied by our enigmatic scribe (fig. 7). In any case, it is implausible that all Maʿrūf’s works under Iskandar would have evaporated without a trace. Thanks to the descent quality of the digital images shared by the MET, it was possible to compare the calligraphic characteristics of his hand – including individual and joined letters, as well as word compositions – in this manuscript with Maʿrūf’s signed works. The result was not unexpected and part of the manuscript was done by Maʿrūf.

The Anthology of Persian Poetry commissioned by Iskandar Sultan (MET, 13.228.19) was copied in Shiraz in 1411. Although the manuscript’s brief catalogue note on the Met Museum website provides some useful information about its illustrations, it does not explicitly disclose the scribe’s identity.

“Spaces for miniatures elsewhere in the volume were left blank and subsequently filled in by Turkman Aq Quyunlu and Ottoman painters, providing a chronicle for the manuscript’s travels. The fine nasta’liq is from the hand of a celebrated scribe who was responsible for a number of Shiraz manuscripts dating between 1405 and 1429.”

It is clear from the scribe’s active years that it does not refer to Maʿrūf – he died in prison in 1427 anyway – but to a second scribe whose signature is found in the manuscript.

Majmū’as Commissioned by Iskandar Sultan

Iskandar sultan was in favour of collected volumes that accommodated a wide spectrum of poems by various poets, and a wide variety of subjects, in forms of anthologies or miscellanies. He treated them as portable mini libraries which he could carry in his pocket during his trips and campaigns. In addition to the Met Anthology, he ordered the following majmū‘as (collected works) during his governorship of Yazd in 1405 and the five years of rulership (1409-1414) in Shiraz and Isfahan: the Yazd Anthology of poetry dated 810/1407 (Topkapi Palace Library, H. 796), Gulbenkian Museum Miscellany dated 814/1411 (LA 161) (fig. 8), the British Library Miscellany dated 813-14/1410-11 (Add. 27261), an anthology of poetry dated 815-16/1412-13 (divided in two parts: Turkish and Islamic Art Museum (TIEM), MS 2044, Gulbenkian LA 158).6

The BL Miscellany begins with the Khamsa of Niẓāmī (ff. 3v-294r), followed by three episodes of the Shāhnāma of Firdausī (ff. 294v-299v), two episodes from the Humāy u Humāyūn of Khwajū Kirmānī (ff. 299v-301r), other poetic genres and subjects.7 Likewise, the Met Anthology begins with the Khamsa of Niẓāmī (ff. 1r-95v), followed by sections of the Shāhnāma (ff. 95v-102r), and a few other texts.

The MET Anthology of Persian Poetry

The BL Miscellany was copied by two scribes for the patron. Isa Waley explains: “Those in the first half of our volume were copied by Muḥammad al-Ḥalvā’ī, and the remainder by Nāṣir al-Kātib; their work is dated 813-814/1410-1411.”8 The Gulbenkian Miscellany was also copied by two scribes: Maḥmūd b. Aḥmad al-Ḥāfiẓ al-Ḥusaynī, and Ḥasan al-Ḥāfiẓ. Likewise, the Met Anthology, completed in 814/1411, is visibly transcribed in more than one hand, despite containing only one contemporary signature.

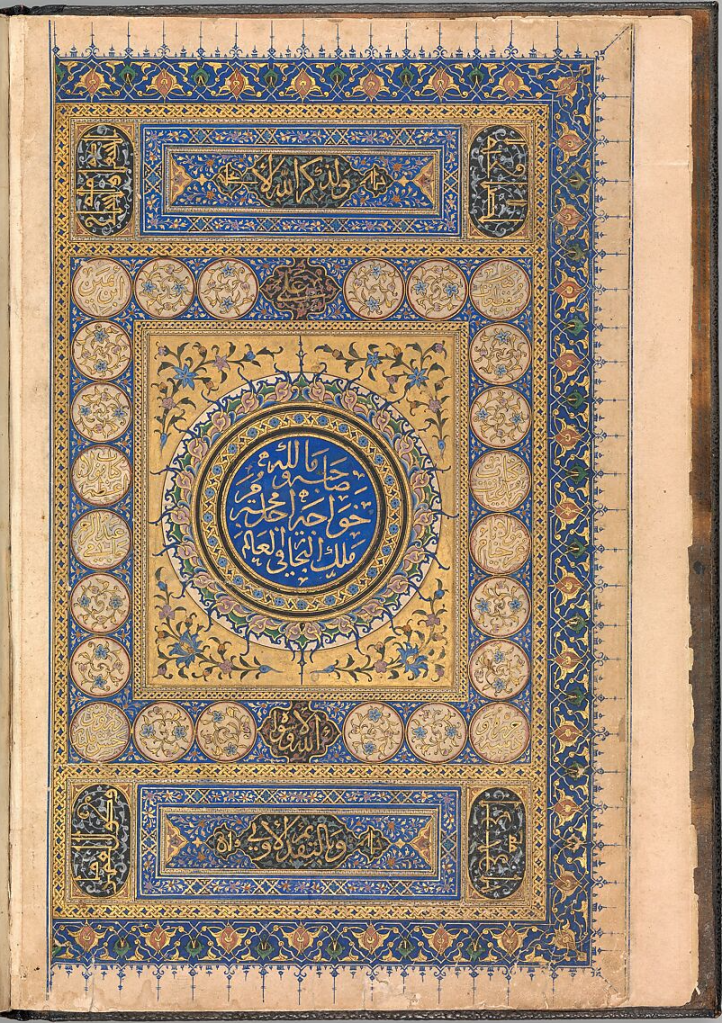

The opening illuminations (ff. 1v-2r) presents four illuminated boxes at the top and bottom of each page, in the Shirazi style of gold floral patterns on blue ground, embracing a frame of circles which bear the name of sections in the anthology (fig. 9). In the heart of each frame an Ottoman illumination is depicted to present the name of the new owner:

صاحبه و مالکه خواجه اجل محترم ملک التجار فی العالم، خواجه کمال الدّین محمود المشتهر با الرومی اصلح الله

(Owned and possessed by the revered khwaja, king of merchants in the world, Khwaja Kamāl al-Dīn Maḥmūd known as al-Rūmī, May God improve him.)

Anthology of poetry.

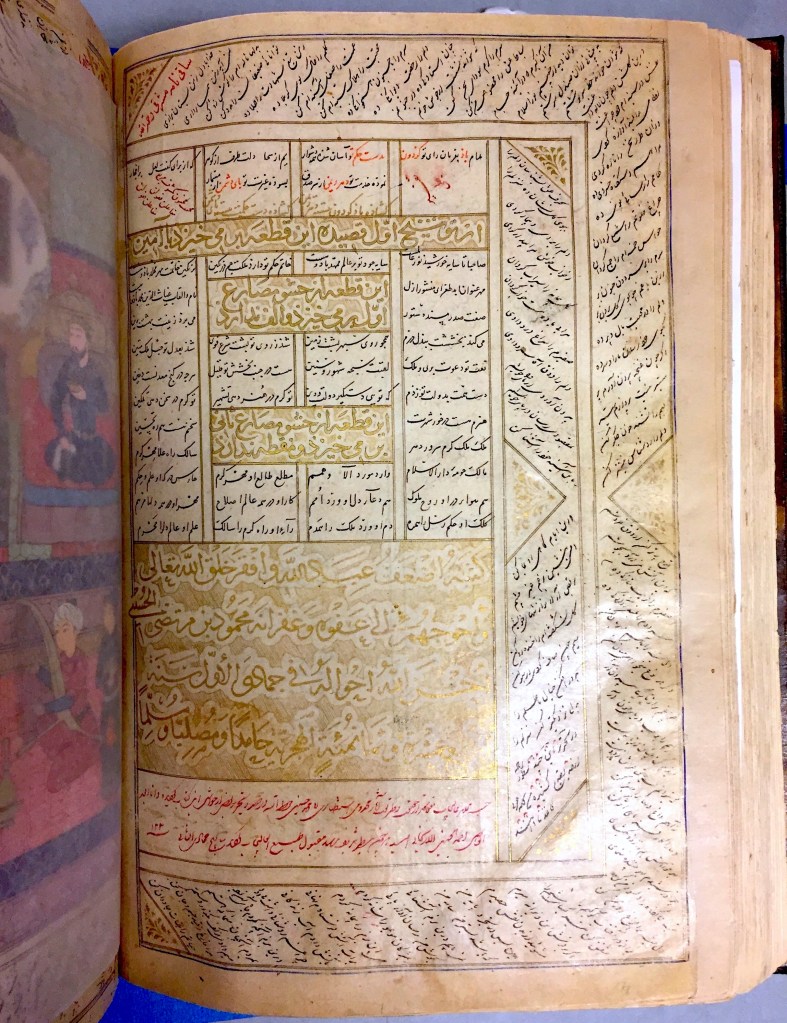

The page layout, illustrations and illuminations resemble those of the Gulbenkian Miscelleny of Iskandar Sultan, which was in production at the same time. It is written in the early nastaʿliq script (Tabrīzī style), opening with the Mantiq al-Tayr of ‘Aṭṭaār Nishabūrī in the margin and the Makhzan al-Asrar from the Khamsa of Niẓāmī in the main text area. The complete Khamsa ending on f. 95r, followed by a brief selection of the Shāhnāma (ff. 95v-102r) are almost certainly in the hand of Maʿrūf, although it lacks his signature. His hand is closest to the Golestan Palace Jung, which in turn helps deducing a better guess for the date of the Jung.9 Folios 103v to 127v carry qasāyid in the main text area and the ghazaliyyāt in the margin in an early nastaʿliq script, clearly different from that of Maʿrūf. The second scribe signs his name in an illuminated colophon (f. 127v): Maḥmūd b. Murtażā al-Ḥusaynī, Jumāda I, 814AH (Aug-Sep 1411). He was an active scribe in Shiraz from 808 to 832 AH (1405-1429).

کتبه اضعف عبادالله و افقر خلق الله تعالی و أحوجهم الی عفوه و غفرانه محمود بن مرتضی الحسینی احسن الله احواله فی جمادیالاوّل سنة اربع عشرة و ثمانمائه الهجریه حامداً و مصلیا و مسلماً

Some parts were added to the manuscript in the 19th century in a shikasta script. The first one appears at the end of Khamsa (f. 95r) in the lower half of the page which was left blank. From f. 97v selected poems from the Būstān of Saʿdī are written in the margin to f. 103r where it expands into the main area as well. The scribe of lines in shikasta has left his signature in f. 127v, after the colophon, stating that some Aqā Muḥammad Ḥusaynī commissioned the added sections to the scribe Aḥmad al-Ḥusaynī al-Arsanjānī in 1230AH (1815) (fig. 10).

The rest of the manuscript (ff. 128v-163r) is in naskh script both in the main text blocks and in the margin. The final colophon does not provide any particular information on the date or the scribe’s identity.

Conclusion

Famous for his skill and speed in copying, Maʿrūf Baghdādī was a royal scribe who served four great rulers and art patrons: Sultan Aḥmad Jalayir, Iskandar b. ʿUmar Shaykh b. Timur, Shāhrukh b. Timur, and Bāysunghur b. Shahrukh. He was the calligraphy teacher of Shams al-Dīn Haravī who was Prince Bāysunghur’s calligraphy tutor. His name appears in most Persian historical and art historical sources in association with his role in a regicide attempt on Shahrukh b. Timur, or his wonderous scribal speed, respectively.

There have been few scholarly publications studying his three signed works, commissioned by Sultan Aḥmad, Shahrukh and very probably Bāysunghur. Even though he spent the peak of his active years supervising and working in the royal library-workshop of the Timurid Iskandar Sultan, and his phenomenal copying of 1500 verses in a day took place under that prince, no single work in his hand had ever been known to have been copied for that patron. This article discusses that a large part of Iskandar Sultan’s Anthology of poetry in Metropolitan Museum of Art (MS 13.228.19) was copied by Maʿrūf Baghdādī, based on a detailed analysis of its calligraphic traits in comparison with Maʿrūf’s signed works.

This newly identified work of such a prominent scribe helps us to improve our knowledge about previous masters of the art of the book. This study demonstrates an important aspect of digital research: Improving digital libraries and providing high quality digital images shared in public domains not only facilitates research for scholars and interested individuals, but also collections will benefit from such investigations and know more about their objects, which often leads to a surge in the object’s value.

—

- Ḥāfiẓ Abrū, Zubdat al-Tawārīkh, ed. S.K. Haj Sayyid Javādī (Tehran, 2001): 915. ↩︎

- Javad Bashari has reviewed this manuscript as one of the oldest extant examples of poems by Ḥāfiẓ. See Basharī, J. “Jung-i Maʿrūf Baghdādī“, Nāma-yi Farhangistān, no. 30 (1385/2006): 124-145. ↩︎

- For a comprehensive study on this incident, see BİNBAŞ, İ.E. “The Anatomy of a Regicide Attempt: Shāhrukh, the Ḥurūfīs, and the Timurid Intellectuals in 830/1426–27”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 23(3) (2013): 391-428. ↩︎

- Titley, N.M. “A Khamsa of Niẓāmī dated Herat, 1421”, The British Library Journal, vol. 4 (1978): 161-186. ↩︎

- The reasons Prince Bāysunghur preferred Jaʿfar over Maʿrūf to direct his artistic projects is discussed in Mihan, S. Timurid Manuscript Production: The Scholarship and Aesthetics of proince Bāysunghur’s royal Atelier (1420-1435), PhD dissertation (University of Cambridge, 2018): Chapter 6. ↩︎

- Two small sections of the Gulbenkian LA 161, are now located in London (Welcome Library, Pers. 474), and Istanbul (Istanbul University Library, F. 1418). For an account of each majmū‘a, see Wright, E. The Look of the Book (Washington D.C., 2012): 85-95. ↩︎

- For the content of the BL Miscellany, see here. ↩︎

- Isa Waley, M. “The Miscellany of Iskandar Sultan (Add. 27261)”, British Library, Asian and African Studies’ blog (2014). ↩︎

- The dates suggested for this manuscript are varied from 784 To 813. For a summary of previous discussions on the Jung‘s date, and a more comprehensive account of Maʿrūf, see my article in Persian: Mihan, S. “Maʿrūf Baghdādī va nakhustīn faʿāliyyat-hā-yi kārgāh-i Bāysunghur Mīrzā”, Nāma-yi Bāysunghur 3 (Herat, 2023): 39-81. ↩︎

Please get a hold of me on Facebook. If not you can reach me at jdferry@protom.me

Thank you for this useful study 🙏👌

I thoroughly enjoyed learning more about the scribe Ma’ruf Baghdadi.Shiva has such a deep knowledge that you can tell she takes great pleasure and pride in her work and research.Thank you

I thoroughly enjoyed learning more about the scribe Ma’ruf Baghdadi.Shiva has such a deep knowledge that you can tell she takes great pleasure and pride in her work and research.Thank you