This entry introduces a platform that utilizes Machine Learning (ML) algorithms from the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) to facilitate research questions for texts written in Classical Chinese. Developed by Peking University’s Research Center for Digital Humanities, the WYD platform (an acronym standing both for wu yu dian 吾与点 and for “Widen Your Data”) provides easy access to run specific NLP tasks specific to and tailored to Classical Chinese on texts in the language. It integrates a deep learning model, trained on a dataset of 3.3 billion characters of Classical Chinese language data, and aims to allow human-machine collaboration for working with Classical Chinese texts (more on this point below). The platform is currently available in two versions: while an earlier version is still available on http://wyd.pkudh.xyz/, a newer website with updated functionality is currently in a testing phase available on https://wyd.pkudh.net/, and is expected to be in a stable state starting April 15, 2024. Note that images below will focus primarily on the earlier user interface. These two versions also differ primarily in their scope: whereas the earlier version imposed a limit of 24 inquiries per day, with each inquiry limited to a maximum of 800 characters, the new platform does not feature such a limit, and promises to allow users to save projects on the platform.

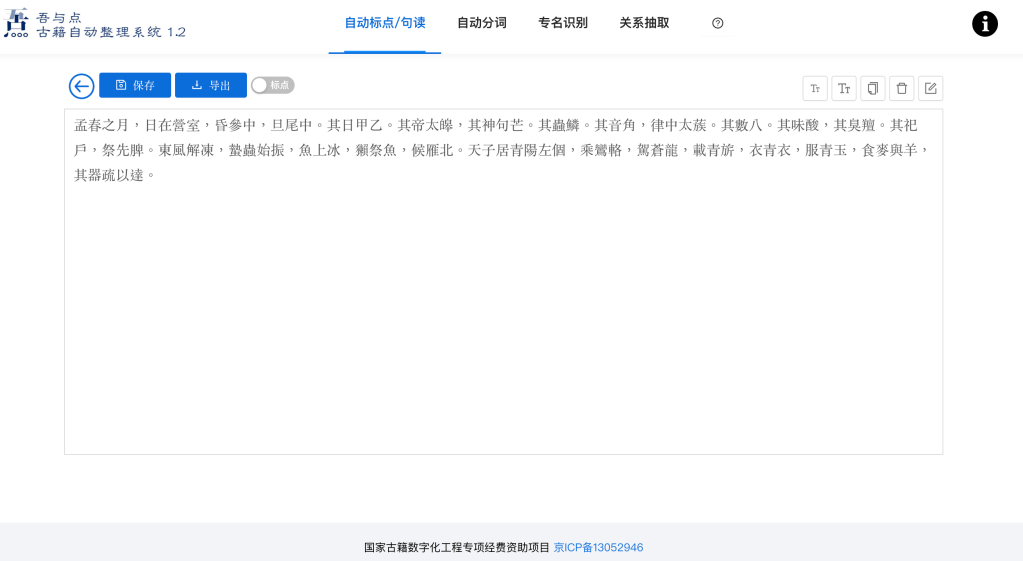

So what does WYD do? While the first of these steps is punctuation prediction, the second consists of automatic word segmentation. Both are forms of segmenting an unstructured string of text into smaller, machine-processable tokens. Generally speaking, NLP processes usually start with segmentation, but for Classical Chinese text, this process is more difficult than for text in English, which offers punctuation and white space. This is firstly because historical documents typically do not contain punctuation in the sense that we are used to today (even though current print publications often add such markers) – which is why punctuation prediction forms a first step towards segmentation.

Image 1: User interface of the WYD platform, with sample input from Lüshi chunqiu 1/1.1, featuring predicted punctuation.

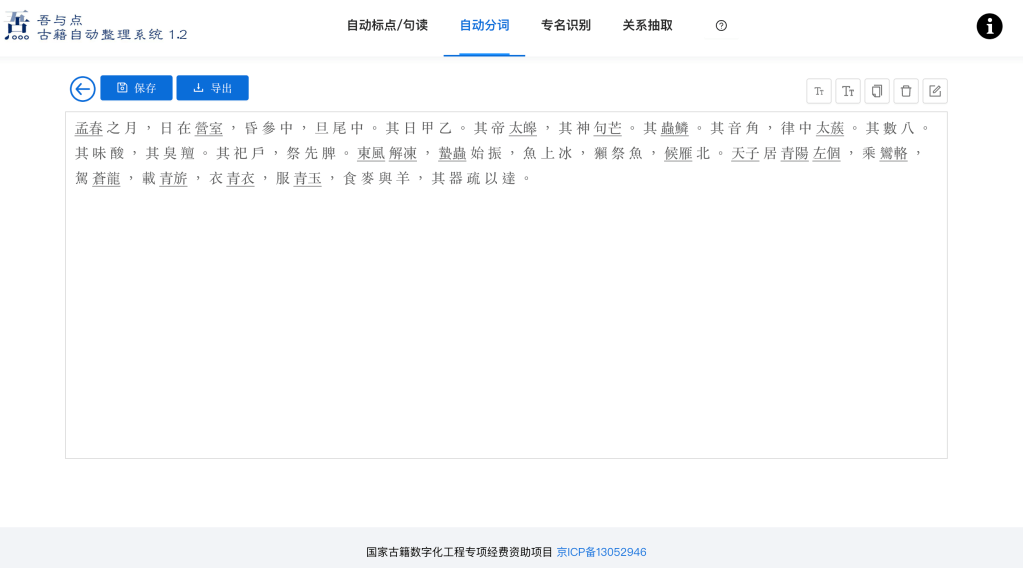

Secondly, through automatic word segmentation, the WYD platform segments strings into shorter tokens. Note that this latter process is well-established for modern Standard Chinese, where a sentence such as “Jīntiān hěn lèi 今天很累” (“I am very tired”) ought to be broken down into three words: jīntiān 今天, hěn 很, and lèi 累. The WYD platform hence applies these two segmentation processes to strings of premodern text, and it does so based on a statistical model, like other contemporary NLP applications. To indicate predicted word boundaries, the WYD platform adds white space. This means that both punctuation and word boundary are predicted according to previously annotated data. Of course, depending on the difference between the model (which is generated from annotated text) and input text, this may result in rather suboptimal predicted segmentations – I am in particular thinking here of material such as excavated texts. Similarly, whether the predicted tokens for Classical Chinese truly form words (cí 词) is, of course, open to debate. Previous posts in the Digital Orientalist covered the rather thorny issue of text segmentation and how to approach it for both modern and premodern forms of Chinese, and for Japanese, and readers would be well advised to revisit those posts on these issues.

Image 2: User interface of the WYD platform, with segmented and punctuated sample input from Lüshi chunqiu 1/1.1. Note the use of white space and underscore to highlight supposed word boundaries.

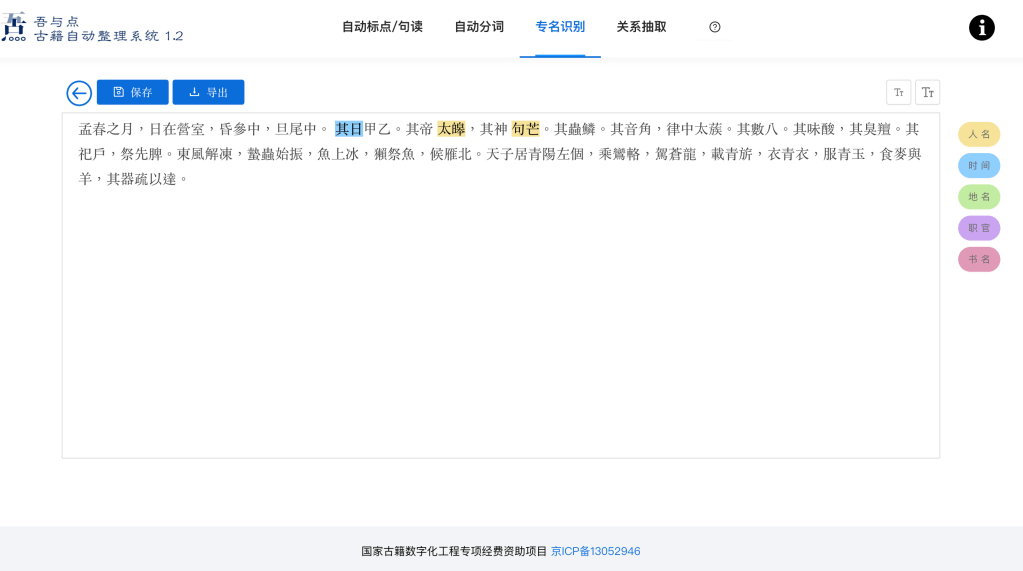

These two segmenting steps allow further processing of the text, and the WYD platform features a task called named-entity recognition (NER). NER aims to identify and extract pre-defined classifications of specific objects (or named entities) within text, including locations, people, books, or products. For the purpose of analyzing Classical Chinese literature, the WYD platform predicts names of people, dates, locations, official titles, and books. NER can be undertaken based on a set of rules, or based on a statistical model (or on a combination of both).

Image 4: User interface of the WYD platform, highlighting the use of NER.

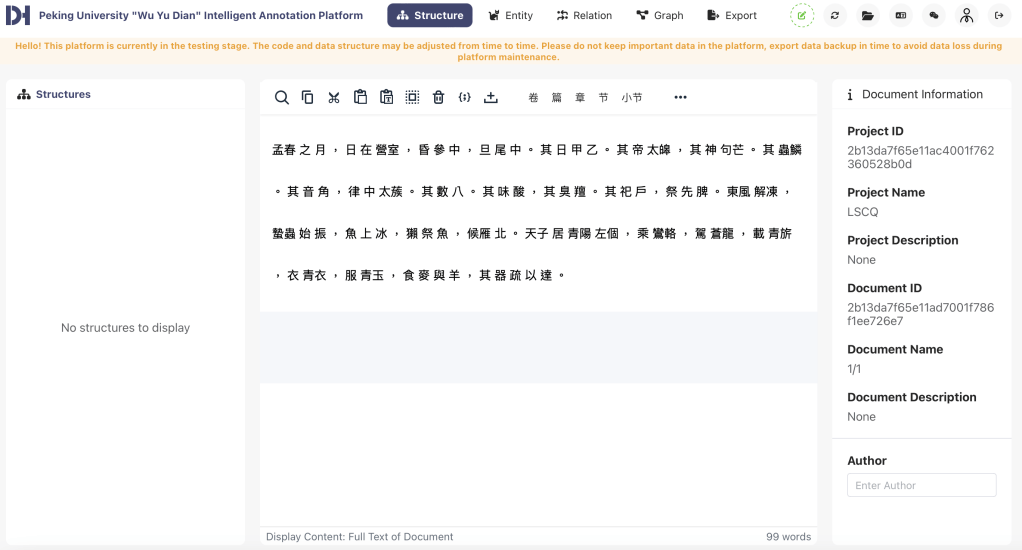

Of course, an automated prediction of named entities can be spotty for a language such as Classical Chinese, which is not only relatively under-resourced, but also used across vast periods of time and across different domains. It is for this reason that the new version of the WYD platform offers additional functionality: specifically, it allows users not only to select what language model to apply to their text (whether the pre-trained Classical Chinese model of the platform or industry-strength Large Language Models (LLM) such as OpenAI’s GPT 4 Turbo, Baidu’s ERNIE Bot Turbo (wenxin yiyan 文心一言 Turbo), or Zhipu AI’s GLM-4), but it also allows to manually annotate their data. Especially with the option to batch annotate named entities by uploading a user’s own database of matching patterns for a given named entity, this can yield much better results, and speaks to the approach underlying the WYD platform of allowing a close collaboration between human and machine. Users of WYD benefit from the automatization of menial tasks, while the platform will make use of user-input data to further improve its ML predictions. As the platform’s overview site confirms, the ML model underlying the WYD platform will be improved continuously, based on the user base’s input. This will without a doubt lead to much better results. At the same, however, it should be expected that the underlying model will only slowly be able to handle edge cases (such as the previously mentioned excavated material) well. There are, of course, also other platforms available for markup of named entities, including MARKUS, reviewed in more detail in this post here on the Digital Orientalist, but WYD’s integration of various language models to automate the task appears particularly appealing.

Image 5: User interface of the new WYD platform, with sample input from Lüshi chunqiu 1/1.1.

The new WYD platform further provides a framework to tag relations between named entities. This allows for relationship extraction (RE), another valuable NLP task. RE detects and classifies semantic relationships between named entities. While the WYD platform also allows for an automatization of this step, the results may currently be suboptimal. But again, it is to be expected that the model will perform considerably better in the future, especially once a stable user-base has been achieved. And this should not take too long, given the capabilities of the WYD platform.

Lastly, the WYD platform further contains a function to transform the mentioned relations between named entities into visualizations. Such knowledge graphs can render complex data into appealing representations. Additionally, the WYD platform allows for easy export of one’s own data in a variety of file formats, in order to work on it either locally or on other platforms. Overall, the WYD platform offers a promising approach to speed up data work considerably, and I am excited to see its impact in our field.

4 thoughts on “NLP Tools for Sinology: Introducing the WYD Platform”