This is a post by Helen Giunashvili | George Tsereteli Institute of Oriental Studies/Ilia State University

The Georgian manuscript tradition and book art have a 16-century-long history. Their origin (the most ancient Georgian handwritten monuments are dated from V-VI cc AD) and subsequent transformation relate to many aspects of the development of civic life in Georgia: religion and political orientation, social relations, educational trends, development of artistic thought, and material culture.

Georgian literature and written culture of the Middle Ages, in accordance with political life, was oriented not only towards the knowledge of Christian thought, but also towards the acquaintance with the written culture of its closest neighbors of Islamic commonwealth – Persian and Arabic civilizations (Chkhikvadze 2012, 105-106).

The earliest secular monuments of Georgian written culture were created in the conditions of an independent and strong feudal monarchy, at the luxurious royal court. It was a society open to external cultural background, which creatively adopted the influences of both the Hellenic-Byzantine and the Islamic East (Chkhikvadze 2012, 91).

From the 11th century onwards, cultural and literary relations with Iran became particularly intense. Despite political and national-religious antagonism, translations and adaptations from Persian originals organically merged with Georgian literature, which was due to the high artistic level of these monuments and the presence of related motifs in Georgian creative and artistic thought (Gvakharia 2001, 481-486; Chkhikvadze 2012, 106).

One of the brilliant monuments of classical Persian writing, “Vis o Ramin” by Fakhruddin As’ad Gurgani (d. 1058), was translated into Georgian during this period. It follows the original version with meticulous accuracy and is an excellent example of Georgian writing with its high literary value (Giunashvili 2000).

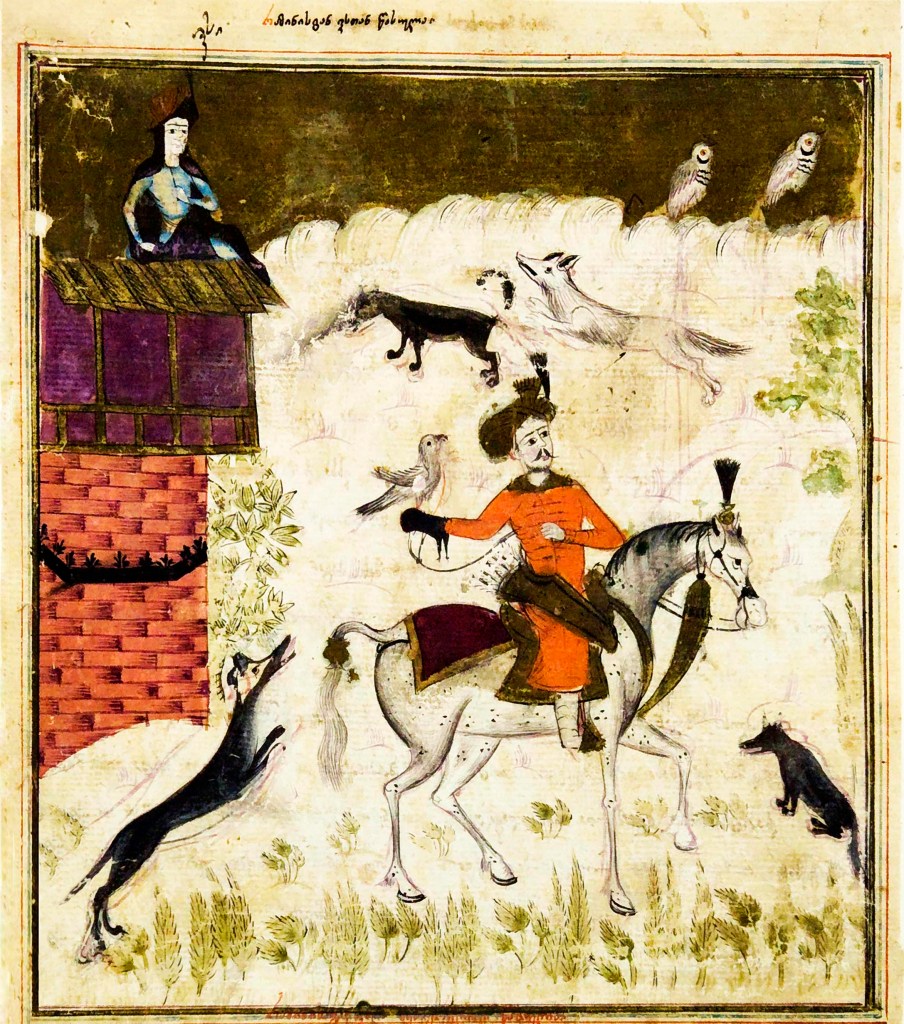

The National Centre of Manuscripts preserves the unique manuscript of “Visramiani” – S-3702 dated by 1729, adorned with miniatures. The painter adhered to the Muslim-Oriental tradition and utilized Persian manuscript-book style to embellish the manuscript.

Photo 1. “Visramiani” (S-3702) miniature, National Centre of Manuscripts.

Abu’l-Qāsem Ferdowsi’s (940-1020) monumental poem “Shahnameh” was well-known for Georgian intellectuals of the time the poem was created. Presumably, it was translated into Georgian rather early (probably at the 12th century), but this translation has not reached us (Giunashvili 2005; Zhorzholiani 2016, 10). Only the 15th-18th century Georgian versions of the ‘Shahnameh’, both written in prose and poetry, are recognized today.

The Georgian manuscript heritage reflects the extensive process of the creation of these versions, as well as the main trends in the development of Georgian secular manuscript illustrations and secular miniatures of that period.

In the 16th century a common national cultural-creative process started in Georgia, known as the “Georgian Renaissance”. This national movement, based on its cultural heritage, covered different fields of education, literature, science and fine arts, adopting and transforming correspondingly on the national basis of cultural achievements within the common Near Eastern cultural area (Abuladze-Giunashvili 2021, 173-174).

The revival of Georgian secular literature in the 16th-17th centuries was a particularly important phase, primarily for Georgian writing as was for the development of Georgian-Persian cultural interrelations. During the Renaissance, there was a revived national self-awareness, with deepening contacts with the Orient, as well as with the West. Cultural-elucidative trends were reinforced, and translational activities were widely promoted.

Precisely in this period, “Shahnameh” drew the particular attention of Georgian poets and interpreters. Most Georgian versions of the poem, both prosaic and poetic, belong to the Renaissance epoch. Obviously, Georgian creators’ passion for the “Shahnameh” was not uncommon ‒ the poem, which was imbued with love for freedom, its generous and incomparable heroes and their adventures, romantic and idealized love stories were mostly close to the Georgian ideology and to the Georgian secular literature’s genre and themes (Abuladze, Giunashvili 2021, 175; Giunashvili 2021, 444).

Georgian versions of “The Book of Kings” directly take their origin from Persian sources and are compiled from separate editions (Baramidze 1936, 141-144; Kekelidze 1958, 323-55; Kobidze 1959; Giunashvili 1980-81 (1359), 863-65; Giunashvili 2005; Giunashvili 2012, 37-44; Gvakharia 2001, 481-486).

A number of these versions are preserved in the collections of the National Centre of Manuscripts. Among them is distinguished “Rostomiani”, written in Shota Rustaveli’s (XII c) poetic form – shairi.

The Georgian version of “Rostomiani” presents those episodes of “Shahnameh” that are related to Rustam, beloved character of Iranian people.

The “Rostomiani” translation was undertaken by the Georgian poet Serapion Sabashvili at the first half of the 16th century. He translated nearly 4,000 verses, from the beginning of the poem till Gostasab’s reign. Persian poetic skills and Rustaveli’s poetry were both a source of inspiration for his translation.

Another Georgian poet, Khosro Turmanidze followed Sabashvili’s footsteps and completed the Georgian poetic cycle of ‘Rostomiani’ in the second half of the 16th century.

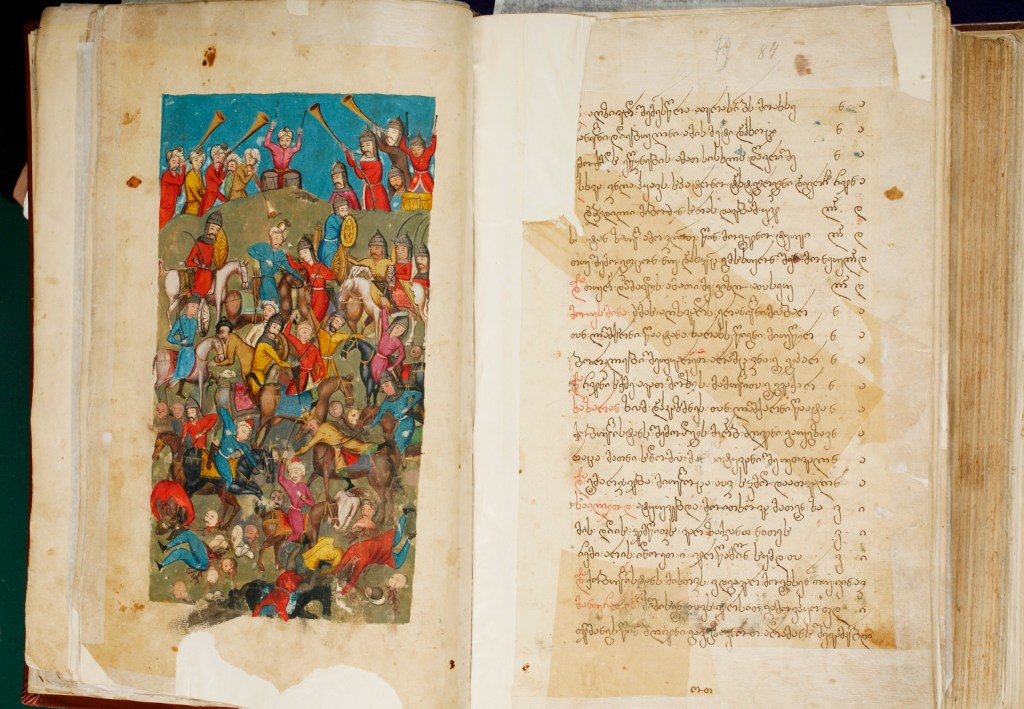

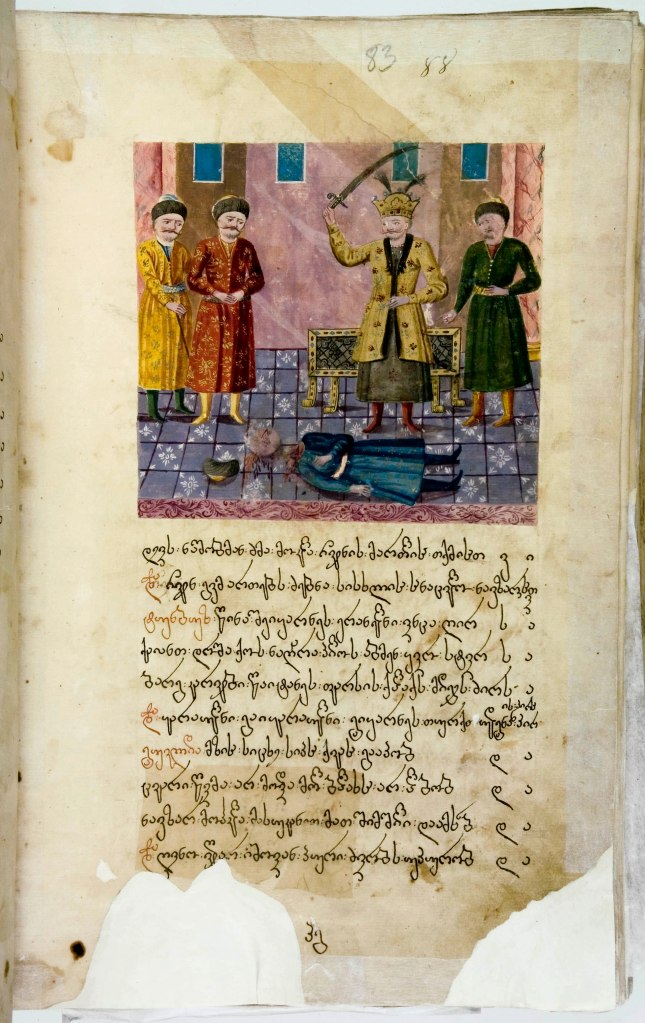

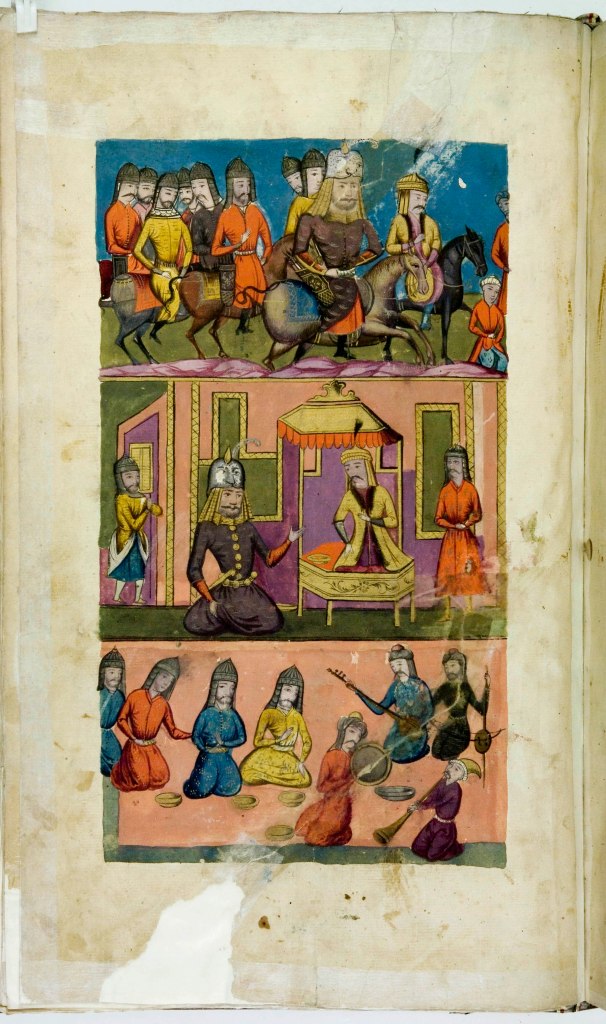

One of “Rostomiani”’s manuscripts, S-1580 (Metreveli 1963, 37-38) is dated to the 17th century (Chkhikvadze 2012, 108-109) and adorned with numerous (61) miniatures.

Georgian secular manuscript painting was raised as a uniform branch in the 16th century, and conditioned by the political and cultural orientation of the country. It was based on the religious books and fresco painting style created in the Georgian monasteries. Its development was also particularly influenced by the so-called folk stream in the culture, although the Georgian manuscripts of this group are still mainly influenced by Persian manuscript books illustrations.

The 16th-18th century Georgian secular miniatures present two main types: 1) Fine illustrations made completely in the Oriental (Persian) style, in a thorough miniature technique, being distinguished by refinement of drawing, colour, and marked with formal achievement (Khuskivadze 1976, 10; Khuskivadze 2018, 30-33; 79); and 2) Painting created on folk, or national, grounds being free from such influences (Khuskivadze 1976, 10-11; Khuskivadze 2018, 32-34; 81).

There are numerous miniatures known as an intermediate group of Iranising works of art, reflecting tendencies characterized for both types of painting, and the striving of Georgian artists for independence (Khuskivadze 1976, 10-11). Exactly to this type of secular miniatures belong drawings of “Rostomiani” (Khuskivadze 1976, 85-95).

Though in the manuscript S-1580 the main painting form is Iranian, the miniatures clearly express features inherent in Georgian painting: more delicate colour schemes, a relatively informal manner of drawing, a stronger emphasis on the ideas central to the contents, peculiarity of iconographic details and a facial type different from the Iranian (Khuskivadze 1976, 161).

It should be mentioned that seeking to highlight their national character and overcome foreign influences, these miniatures still reveal the mastery of their artists and maintenance of the whole line of development of Georgian secular miniatures.

Here are some examples of S-1580 manuscript miniatures:

Photo 2. 78v -79r; dimensions: 15.35 X 10.63 cm; resolution: 300 dpi

Photo 3. 083r; dimensions: 25.61 X 40.63 cm; resolution: 240 dpi

Photo 4. 089r; dimensions: 25.59 X 40.63 cm; resolution: 240 dpi

Photo 5. 129v; dimensions: 24.03 X 40.63 cm; resolution: 240 dpi

Photo 6. 140v; dimensions: 24.30 X 40.63 cm; resolution: 240 dpi

References

Tamar Abuladze, Helen Giunashvili, “Georgia and Iran: Historical-Cultural Context and Tendencies of Georgian Renaissance (According to Georgian Handwritten Heritage)”, Pro Georgia. Journal of Kartvelological Studies, vol. 31, 2021: 173-192.

Aleksandr Baramidze, “Le Schah-Naméhde Ferdousi dans la litérature géorgienne”, Proceedings of the State Museum of Georgia, vol. IX., Tbilisi 1936: 141-144.

Nestan Chkhikvadze (ed.), Georgian Manuscript Book. 5th-19th Centuries. Album, prepared by Maia Karanadze, Lela Shatirishvili, Nestan Chkhikvadze with participation Tamar Abuladze, Tbilisi, National Centre of Manuscripts of Georgia, 2012 (in Georgian).

Jamshid Giunashvili, “The Georgian Versions of “Shahnameh”, Āyande, 6, No. 9-12, Tehran, 1980-81 (1359): 863-65 (in Persian).

Jemshid Giunashvili, “Visramiani”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, online version, originally published in January, 2000 (updated in 2013): https://iranicaonline.org/articles/visramiani

Jemshid Giunashvili, “Šāh-nāma Translations ii. Into Georgian”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, online edition, 2005: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sah-nama-translations-ii-into-georgian

Jamshid Giunashvili, “Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh in Georgia”, Selected Essays on Iranian Studies and Georgian-Iranian Historical-Cultural Relations, Tbilisi, Universal, Edition of the Cultural Section of Embassy of Iran in Georgia. Series of Georgian-Iranian Association for Cultural and Scientific Collaborations, No. 11, 2012: 37-44 (in Persian).

Helen Giunashvili, “Dialogue about “Shanameh” in Georgia”,Words of Knowers, Discussions with Specialists of “Shahnameh” , edited by Mehrdad Mohammad and Ja’far Yahaghi, Negāh e Mo’aser, Tehran, 2021: 441-445 (in Persian).

Aleksandr Gvakharia, “Literary Contacts with Persia”, Encyclopaedia Iranica vol. X, Fasc. 5. New York 2001, pp.481-486, online version: http://www.iranicaonline.org /articles/georgia-iv–1.

Korneli Kekelidze, A History of Georgian Literature, vol. 2., Tbilisi University Press, Tblisi, 1958 (in Georgian).

Iuza Khuskivadze, Georgian Secular Miniature. XVI-XVIII Centuries, Metsniereba, Tbilisi, 1976 (in Georgian, summary in Russian and English).

Iuza Khuskivadze, Islam in Georgian Fine Arts and Architecture, Sezan, Tbilisi, 2018 (in Georgian and English).

Davit Kobidze, The Persian Sources of the Georgian Versions of “Shah-Nameh”, Tbilisi University Press, Tblisi, 1959 (in Georgian, summary in Russian).

Elene Metreveli, A Register of Georgian Manuscripts), the “S” Collection , vol. III., Edition of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, Tbilisi, 1963 (in Georgian).

Lili Zhorzholiani, Ferdowsi’s “Shahn-ameh” in Georgia, Universal, Tbilisi, 2016 (in Georgian and Persian).

საინტერესოა! სიამოვნებით გავეცანი