Over the past year, I have been working on a textual analysis project exploring Japanese understandings of Judaism, Israel, and Zionism during the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō periods (1912-1926) as a part of a fellowship at Brandeis University’s Schusterman Center for Israel Studies, Institute for Advanced Israel Studies. In fact, I am writing this article whilst at Brandeis attending the Institute’s Digital Humanities in Israel Studies conference and am reworking some of the materials that I presented there. As part of the project, I have been experimented with a few textual analysis methods including the use of Voyant Tools. We have published on Voyant Tools in The Digital Orientalist before including its use for Chinese and Japanese, however, here I want to write about my experiences and difficulties using a much larger corpus particularly as they relate to segmentation.

I had only ever used Voyant Tools on quite small corpora, but for this project I used it to analyse a corpus consisting of 305 texts. This presents an immediate difficulty—Voyant Tools tends to crash or return errors when such a large corpus is used. I found that using the version of Voyant Tools hosted by the LINCS project (https://voyant.lincsproject.ca/) offers greater stability, and therefore I primarily used this version.

As I have discussed elsewhere (including in relation to Voyant Tools) the process of segmenting Japanese text—a first step to textual analysis—is usually paired with morphological analysis. This is because morphological information is used as part of the segmentation process. As a result, verb and adjective stems are often split from different suffixes resulting in the inclusion a large number of auxiliary verbs, inflectional suffixes, and particles as separate segmented units. These are not necessarily useful for analysing a text and therefore are often removed prior to analysis by using a stopword list.

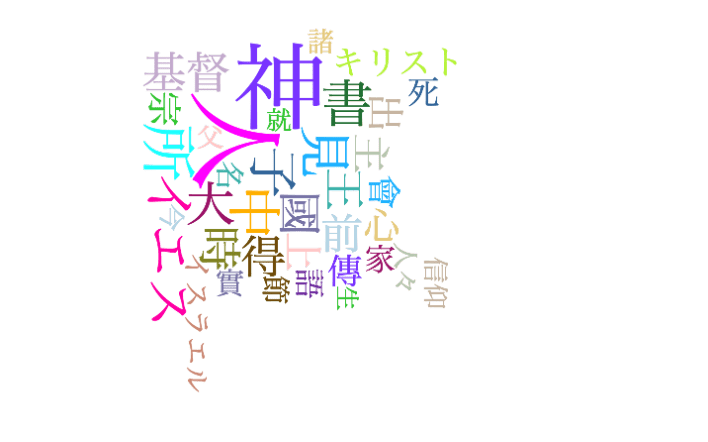

The Cirrus feature of Voyant Tools which is used to create word clouds helps to demonstrate this issue. Without using stopwords, the data for my study produces the below word cloud (Fig. 1). Prominent units are te て (conjunction, imperative command, auxiliary verb attachment), ta た (past tense indicator), ru る (a type of verb ending) etc. In this form, data doesn’t allow us to discern much about the corpus.

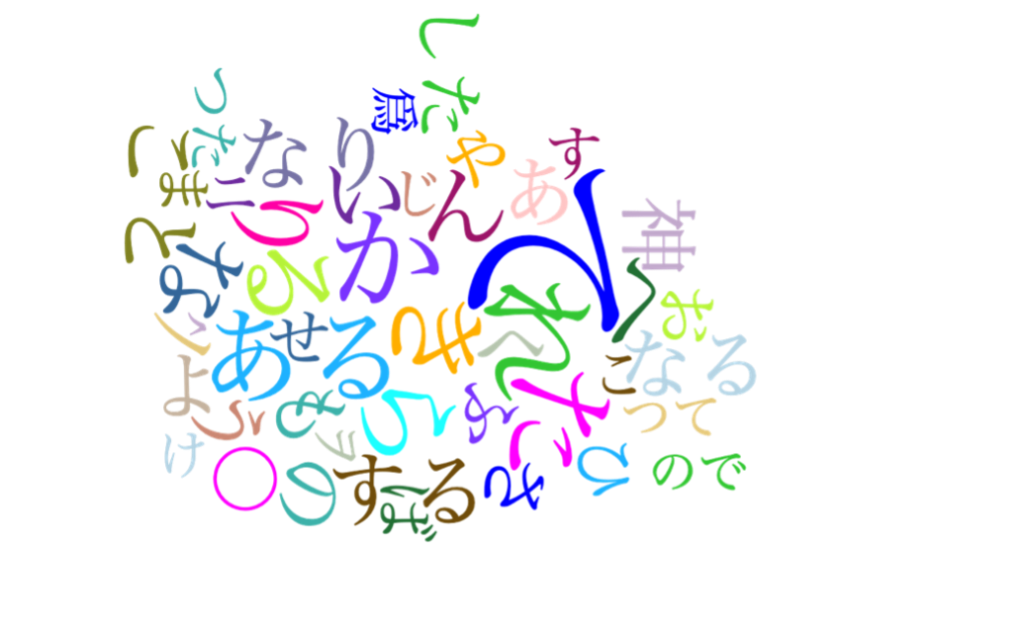

By introducing stopwords (see how to do this here), one can begin to create a more useful visual. Initially, I used a list of 252 terms that mostly consisted of kana (Japanese syllables) and numbers. As some readers have likely observed, the above word cloud is mostly made of Japanese syllables and it seems to me that when using a large corpus Voyant Tools tends to incorrectly segment a large number of kana as individual terms even when they are not acting as such. This is likely linked to the fact that Japanese text segmentation can be inaccurate when a system has to deal with terms that don’t exist within its dictionary. This issue is particularly prominent when it comes to historical texts. In any case, even with a stopword list of 252 terms, I observed that the word clouds that I could produce with Voyant Tools did not allow me to garner much useful information. In turn, this raised some more general questions about the use stopwords, which I haven’t seen being widely discussed. What words should be included in a stopword list? How many stopwords can one include without damaging the integrity of the data? Since it is possible to constantly tweak the visualization of data through the use of stopwords, where should one ultimately draw the line?

The visual that resulted from using the 252 stopword list (Fig. 2) allows us to see the prevalence of terms such as hito 人・ひと (person), kami 神 (god), Iesu イエス (Jesus), Kirisuto 基督 (Christ), kuni 國 (country), ō 王 (king), and so one. These terms might begin to tell us something about the texts in the data including, for example, a focus on religion (as indicated by the word god), Christianity (as indicated by the words Jesus and Christ), geopolitics (as indicated by terms such as country and king), and people (indicated by the inclusion of the term). Indeed, taking into account other available information such as the thematic nature of the texts included in the corpus, we might be able to begin to explain the prevalence of some of these terms. Simultaneously, however, the majority of terms included in the word cloud including nanji 爾・汝 (thou), shika(re) 然 (but), toki 時 (time/when), mae 前 (before/in front of), mata 又 (or/also) etc. represent parts of speech that are unlikely to be useful for textual analysis. These seemingly “less useful” terms can, of course, be removed by adding additional stopwords. Even then matters are more complicated. Some of these terms may indicate something about the contents of the texts, the word thou, for example, is often used in Biblical quotations in Meiji and Taishō period texts.

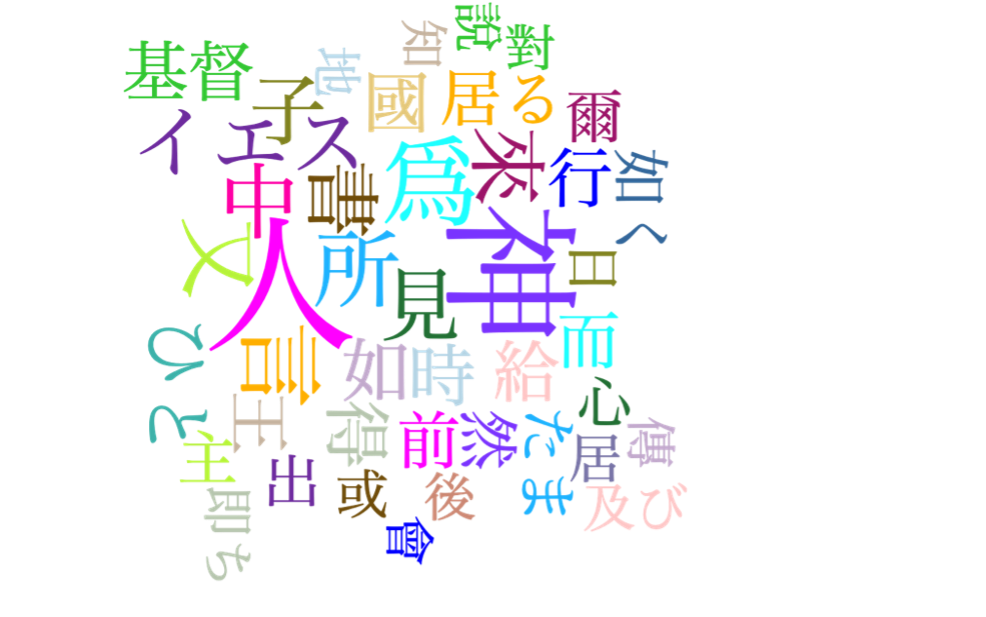

As a quick aside for those who are new to Japanese textual analysis, the loss of suffixes means that most verbs and adjectives appear as single kanji (Chinese characters). As such, we have to interpret some of the characters here by imagining what they may be when used in the corpus (or better yet actually delving into the texts to have a look). For example, the above word cloud includes characters such as ken 見 and gyō 行 that in all likelihood actually represent the prevalence of the verbs to see and to go (in various tenses and forms). This can be a bit jarring at first for those of us not used to seeing this sort of data.

I worked on whittled away terms or characters that I determined (quite subjectively, I must say) to be “less useful” for analysis producing a stopword list of 325 terms. This helped to create the following word cloud (Fig. 3) and here we can begin to make some greater insights. This visualization helps to affirms the Christian-oriented nature of much of the data with multiple terms for Jesus and Christ present in the word cloud (three in total). Other terms may also point to Christian themes with terms such as Chichi 父 (Father) and Ko 子 (Son) appearing. Of course, these could equally indicate a focus on the family, but due to what I know about the corpus I am able to determine that whilst some instances of these terms will be references to familial relationships many will also be instances of Trinitarian terminology. Further study and a statistical analysis would of course allow us to determine a clearer picture here. The thematically religious nature of much of the data is also affirmed with the inclusion of terms such as shū 宗 (religion or teaching) and shinkō 信仰 (faith or belief). In addition to the word for country, Isuraeru イスラエル (Israel)appears as one of the most common terms, which is particularly important for the research questions being explored as part of this project.

Nevertheless, even after increasing the size of the stopword list we can observe the presence of multiple terms that potentially don’t aid in and may even hamper our interpretation of the corpus by overshadowing terms that are richer in meaning. Indeed, some I chose to keep because I was concerned about removing “too many” words and getting stuck in a never ending process of term removal. I fear that the question of where to draw the line is highly important and although I cannot answer it myself it is something that we should all be considering and discussing.

I hope that this short exploration shows some of the issues that arise when using platforms such as Voyant Tools to begin to analyse larger corpora. In the case of Japanese, we can observe that the use of stopwords helps to increase the interpretability of the data, but there are some important questions to be asked about the extent to which stopwords can and should be used.

Made possible through a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Kakenhi, Grant No. 23K12032) and Brandeis University, Institute for Advanced Israel Studies Fellowship.

2 thoughts on “On Voyant Tools, Stopword Lists, and Japanese Textual Analysis and Visualisation”