This article examines the flow of Ottoman citizens, including Armenians, Jews, Christians, and Muslims, to the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Migration from the Ottoman Empire to the United States has not been explored as extensively as migrations from Europe or the Far East, nor is it widely studied by Ottoman or Turkish historians. Using Flourish to visualize the number of Ottoman migrants who crossed the Atlantic and settled in the New World, I aim to shed light on the Ottoman migration experience to the United States and to situate migration from the Mediterranean region within the broader context of nineteenth-century global migration, which is a new trend in Ottoman migration historiography.

Flourish

Flourish was created in 2018 with a focus on storytelling through creating interactive content, maps, and data explorers. Thousands of organizations have used Flourish since its launch, and it has reached millions of viewers every day without the costs and delays of custom-built projects. The tools are inbuilt and require no coding, so it is ideal for those new to DH looking to try visualization software for the first time. At Flourish there are more than 30 different types of charts and maps which are free and available to everyone. Additionally, it provides premium templates that are available to paid users. It is also dedicated to promoting accessible visualizations that ensure everyone can understand and engage with data.

To make a visualization with Flourish is straightforward: users first sign up and log in, select a template that fits their data, upload their data, change the look and style using the editor, add interactive features like filters and pop-ups, and then share it by publishing or embedding it on a website. One can also download an image of their charts or video to share on social media.

By adopting AI-based technologies like Flourish, researchers can enhance the appeal of such studies through compelling visualizations, which also increases their visibility in academic literature. Its tools allow migration trends, demographic distributions, and regional patterns to be displayed clearly, which enhances the reader’s understanding of large-scale historical phenomena. This study represents an introductory effort at using Flourish and can be further developed in future research on DH and migration patterns.

Visualizing Ottoman Migration to the United States

One of the main challenges in studying Ottoman migration to the United States is the inconsistency in migrant numbers, due to the lack of accurate registration records, making this an exciting yet complex topic to research. Although the exact number of people who migrated from the Ottoman territories to the United States remains unknown, I have tried to illustrate the presence of Ottoman communities, including Syrians, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and Turks in the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, based on figures provided by historians whose research focuses on Ottoman migration to the New World.

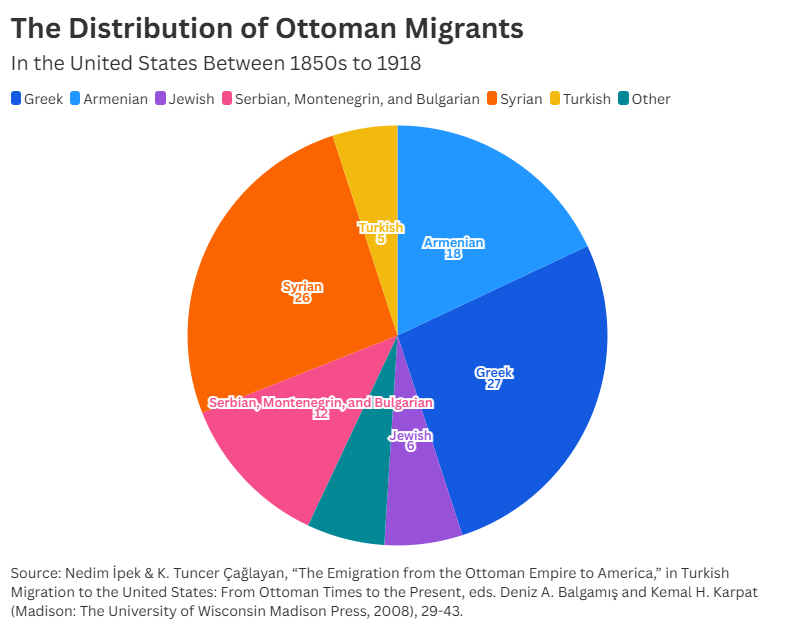

The ethnic makeup of these migrants is estimated to be 27% Greek, 18% Armenian, 6% Jewish, 12% Serbian, Montenegrin, or Bulgarian, 26% Syrian, 5% Turkish, and 6% other groups. In addition to North America, South American countries also received significant numbers of Ottoman migrants. Argentina admitted between 169,000 and 180,000, while Brazil received approximately 77,000, the majority being Christian Arabs of Syrian and Lebanese origin. Muslim Arabs joined the migration wave later, and their numbers remained comparatively small (İpek and Çağlayan 2008: 35).1

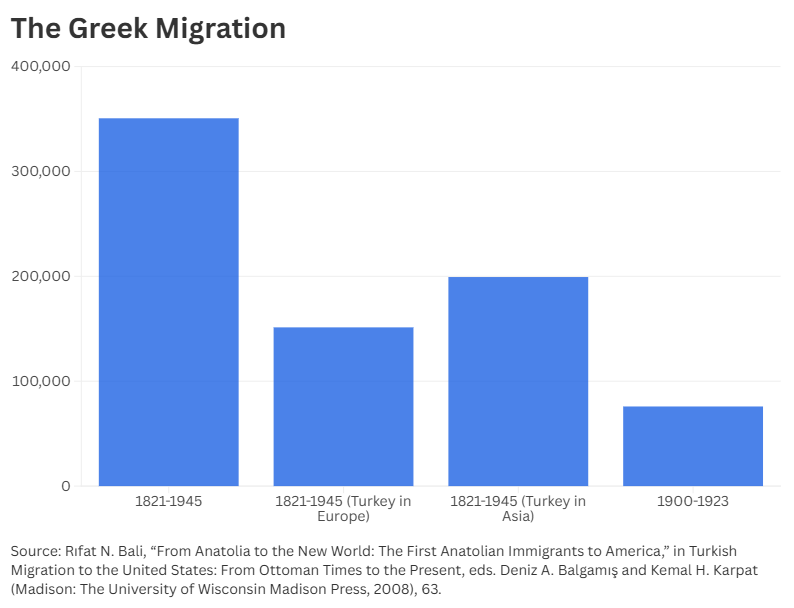

United States Customs officials on Ellis Island classified those arriving from the Ottoman Empire, regardless of religion, as from “Turkey in Europe” or “Turkey in Asia.” For example, Armenians were listed under “Turkey in Asia,” complicating efforts to determine the exact number of Ottomans who migrated to the United States (Karpat, 1985: 181). Thus, while it is difficult to determine the actual figures, scholars estimate that only about 301 Ottomans arrived before 1870. These early statistics are not very reliable due to the lack of accurate registration records, as visualized below.

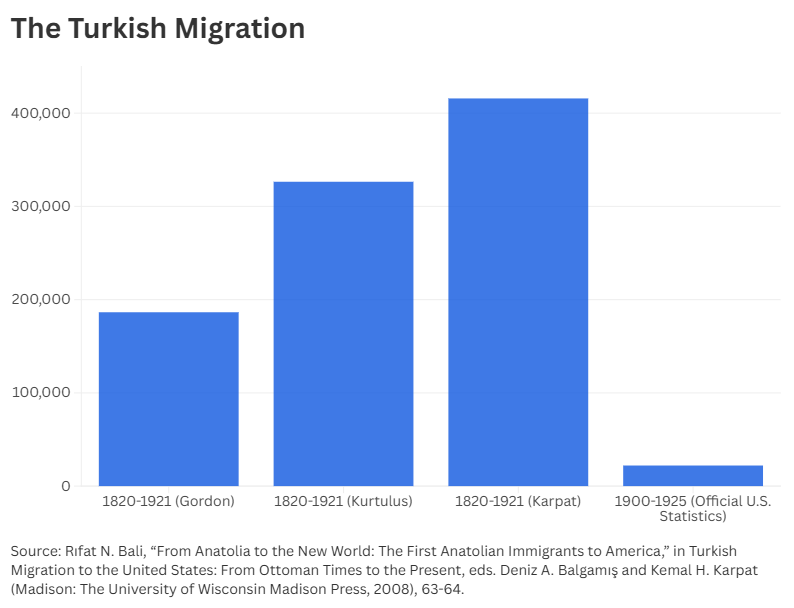

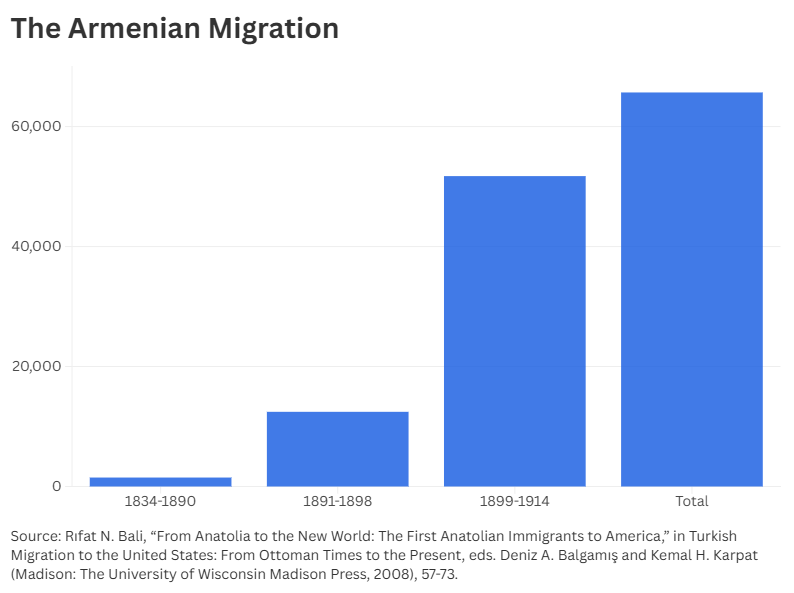

After the conflict between the Armenians and the Ottoman state, migration surged, with around 43,497 arriving between 1891 and 1892 alone. By 1908, more than 150,000 people from the Ottoman Empire were living in the US. During World War I, however, the number of arrivals dropped to about 6,000. Overall, between 178,000 and 415,000 Ottomans are estimated to have migrated to the United States (İpek & Çağlayan 2008).

While each Ottoman community represented diverse migration patterns, the general trend in these charts suggests that migration increased from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. Initially motivated by economic factors, migration from the Ottoman Empire to the United States intensified due to the compulsory military conscriptions, ethnic tensions, and political instability toward the turn of the twentieth century until World War I. While the Muslim population of the Empire left their homeland for better economic opportunities in the New World, it is primarily the non-Muslims who made up the larger portion of Ottoman migrants in the New World.

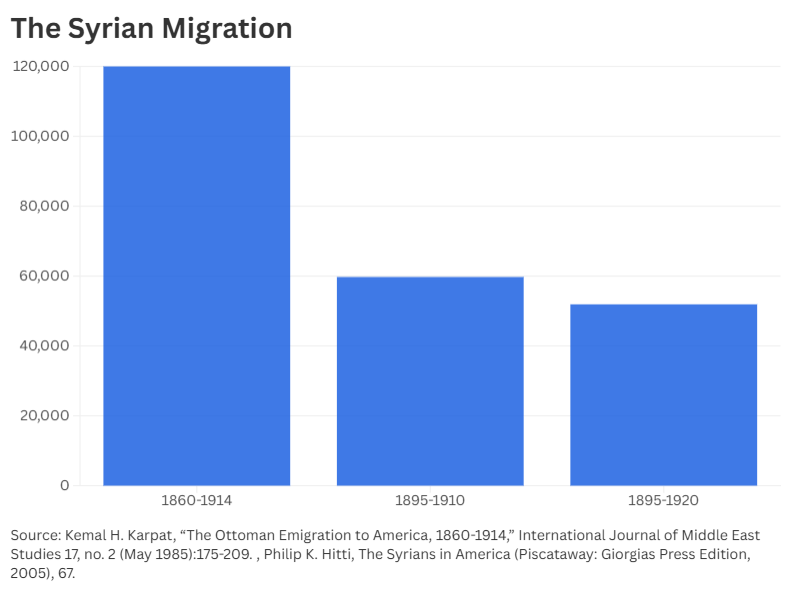

According to available statistics, the total number of Ottoman migrants to the Americas between 1860 and 1914 was around 1,200,000. Of these, approximately 600,000 were Arabic-speaking migrants from Syria and Mount Lebanon, making them one of the largest groups to migrate to the Americas from the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the general economic instability within the Empire, specific factors influenced certain groups of people to migrate. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, for instance, played a significant role in causing Syrians to migrate, as it changed the trade routes southward. Similarly, the destruction of vineyards by phylloxera, a tiny insect that feeds on grapevine roots, and the collapse of the silk industry were among the key economic reasons for Syrian migration between 1875 and 1885 (Karpat, 1985:178, 185). Additionally, the post-war population transfer following 1923, known as the “population exchange,” led the Greeks to flee Turkey for the United States.

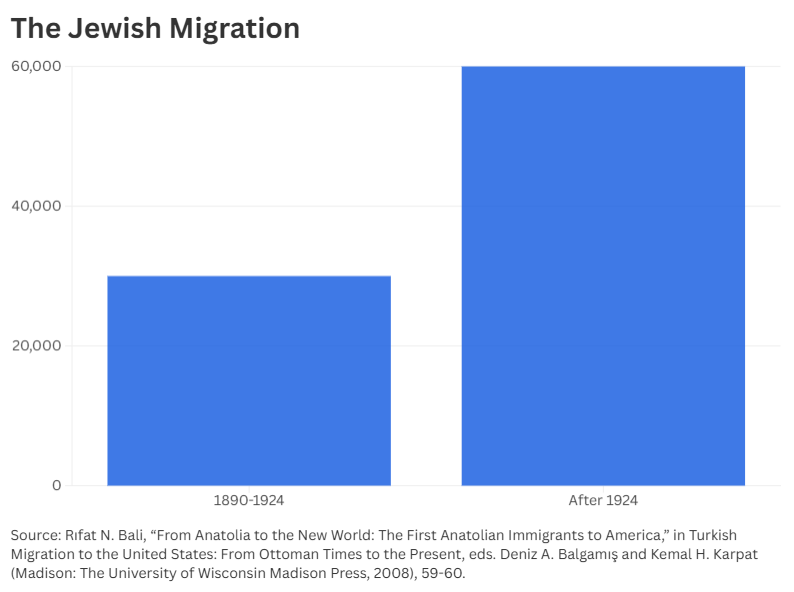

There is no consensus on the number of Ottoman Jews who immigrated to the United States. Marc Angel estimates that around 30,000 Jews from the Middle East arrived between 1890 and 1924. In contrast, Louis M. Hacker stated in 1926 that about 40,000 Sephardic Jews were living in New York alone. If we include another 20,000 Jews living in other North American cities at the time, the total would be about 60,000 (Bali, 2008: 59-60).

Conclusion

Flourish is a useful platform for scholars in the humanities and educators who are not very tech-savvy. It is also a gateway for those who are new to the DH. In this introductory article, I attempted to present statistics on the number of migrants from the Ottoman Empire to the United States. This work represents an initial step in the field. Although it is difficult to determine the actual figures, due to the lack of exact data on Ottoman migrants in the New World, this study combines secondary sources with AI-based technology to visualize what they show. It has the potential to benefit scholars of Ottoman and American history, as well as those in DH, and can be further developed.

As Flourish is data-driven there are limitations in what it can show us. For example, it does not enable the visualization of migrant settlement patterns upon arrival in the United States, as there is a lack of specific data regarding the distribution of Ottoman migrants across individual states. As a storytelling device, it cannot bridge the flaws in existing datasets, and it is up to us to interpret what it shows within the data. What it can do is give us a snapshot of some of the underlying discrepancies and glimpse potential trends and avenues for further research.

- Rıfat N. Bali (2008) also offers a comprehensive analysis of this composition for each Ottoman community in Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present. ↩︎

References

Rifat N. Bali, Anadolu’dan Yeni Dünya’ya: Amerika’ya İlk Göç Eden Türklerin Yaşam Öyküleri [From Anatolia to the New World: The Life Stories of the First Turks [Anatolians] Who Immigrated to America (İletișim: İstanbul, 2004).

Rifat N. Bali, “From Anatolia to the New World: The First Anatolian Immigrants to America,” in Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present, ed. Deniz A. Balgamış and Kemal H. Karpat ( Madison: The University of Wisconsin Madison Press, 2008), 57-73.

Philip K Hitti, The Syrians in America (Piscataway: Giorgias Press Edition, 2005).

Nedim İpek and K. Tuncer Çağlayan, “The Emigration from the Ottoman Empire to America,” in Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present, ed. Deniz A. Balgamış and Kemal H. Karpat ( Madison: The University of Wisconsin Madison Press, 2008), 29-43.

Kemal H. Karpat, “The Ottoman Emigration to America, 1860-1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (May 1985): 175-209.

One thought on “Flourish: Visualizing Ottoman Migration to the United States”