For the past year and a half, I have worked as a digitisation quality assurance and team leader at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. In this article, I would like to demonstrate ways in which digitising RBG Kew’s collections facilitate a new avenue of digital storytelling with herbarium specimens. The collection is vast, and there is a fair amount of “armchair travelling” while working with digitised specimens from all over the world. Particularly as a tribute to my work at Kew, and to the DO, I will use this article to examine several digitised Japanese specimens, meanwhile showcasing Kew’s new database platforms, digitisation techniques, and digital collections now becoming available to the public.

Before working in an herbarium, I had no background in botany and was honestly unaware of the breadth of materials it could hold, and I quickly found out that Kew is a unique botanical repository. Kew holds one of the world’s largest collection of historical plant specimens, which includes 95% of plant genera in the world. Reflecting this, the digitisation project at Kew is one of its largest and most ambitious undertakings to date. Beginning in 2022, the project set a target of digitising all 7.5 million herbarium specimens and 1.1 million fungarium specimens by March 2026. Alongside the physical imaging and uploading of specimens to Kew’s new data portal (which can be used but is still in its beta stages), where as of September 2025, 6.54 million records are currently available. Moreover, the project has involved implementing a new ICMS (integrated collection management system) powered by Earthcape which you can read more about here. As of this year, data for multiple collections across Kew’s Science Directorate has been successfully migrated onto its ICMS and this now allows for greater consistency and standardisation in metadata and cataloguing, as well as more efficient cross-collection dialogue and research.

Digital Storytelling Through Herbarium Specimens

At the most basic level, the image taken by Kew’s digitisation officers captures information about the dried and mounted specimen, such as physical appearance, as well as collection information written or typed on a label also mounted on the sheet. In addition, images of the herbarium specimens are valuable in detailing any redeterminations of species and any other researcher notes which are sometimes written in pencil directly on the herbarium sheet. By layering our examination – combining this image with metadata, collector and collection details, and the ability to cross reference with other forms of the specimen such as microscopy and illustrations – the digitised record becomes a richer narrative artefact and these images provide varying perspectives of the same species.

For the purposes of this article, I will focus on various species of Wisteria, a flowering plant from the Fabaceae family and one of my favourite flowers. There are four main species of wisteria. Wisteria floribunda otherwise known as Japanese wisteria, as well as the species brachybotrys and japonica are all native to Japan and naturally grow across central and south Japan, particularly the islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, with the oldest wisteria in Japan found in Ashikaga Flower Park in Tochigi prefecture. The most common species of Wisteria, sinensis or chinensis, is native to China but was cultivated in Japan in approximately 1816.

Below are a few examples of various species of Wisteria collected from Japan in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century and provide a sense of the stories and discoveries stem from the digitised specimen and what we can learn from it.

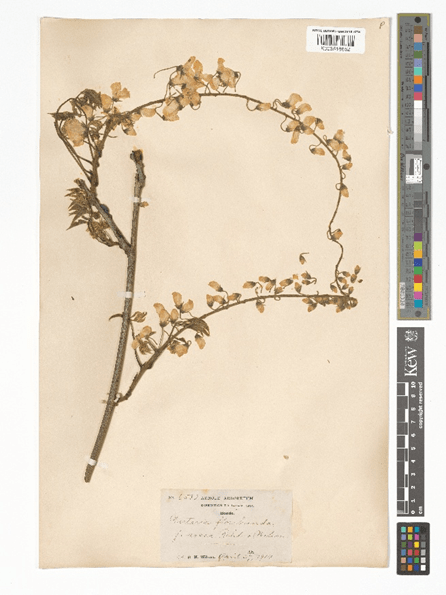

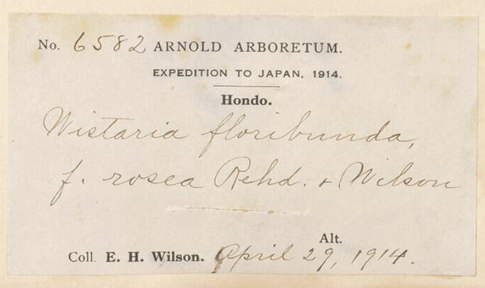

This first herbarium sheet I’ve included (see image 1) is of a Wisteria floribunda specimen and was collected by Dr. Ernest Henry Wilson in April 1914. Wilson was a prolific botanist and collector, collecting over 2,000 specimens from across Asia, bringing them to the West and gaining the nickname “Chinese” Wilson. Wilson also authored Wisteria venusta f. plena, a synonym of the Wisteria brachybotrys. You can find a record and image for this specimen here (which happens to be from the same expedition as the first specimen). Looking at the sheet, you can see the colour of the dried flower has changed from when it was alive, but there are clear characteristics of the species: climbing woody stem, with long leaves and loosely tapering flowers (Compton and Lack: 219). You can also find the collection label detailing the expedition, collector number, species determination, collector and date.

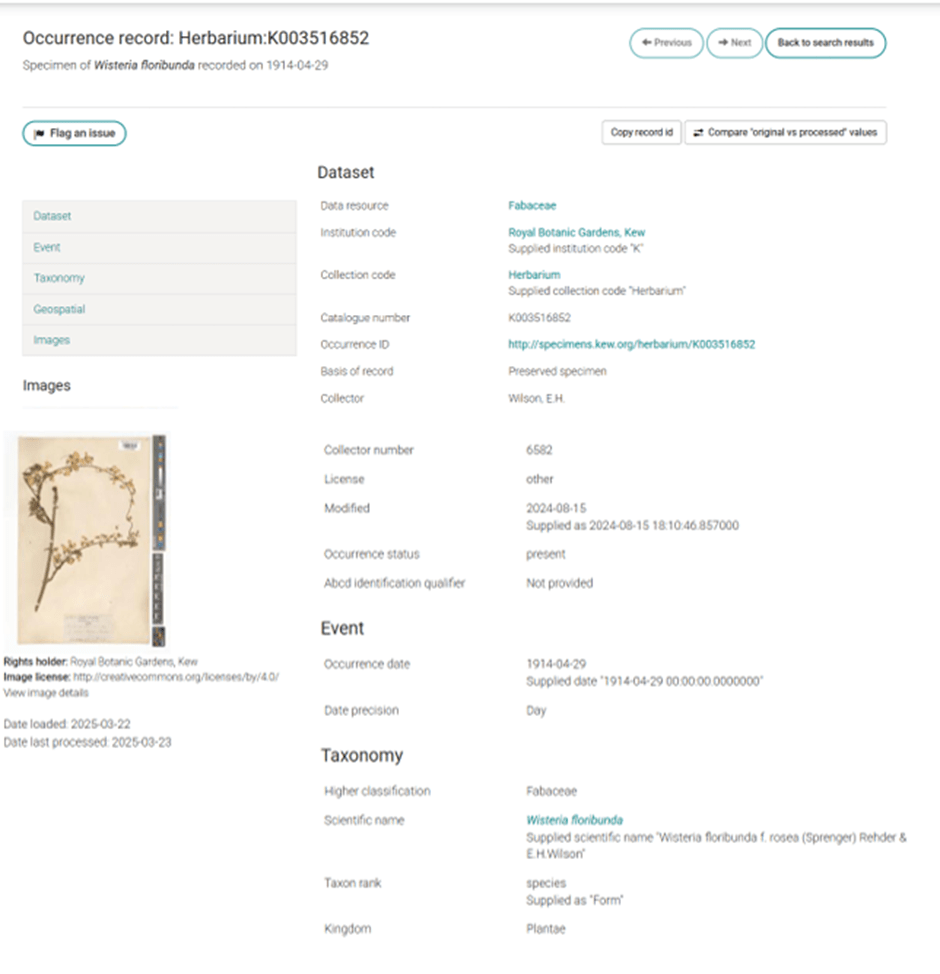

The digitisation process involves imaging herbarium specimens with mostly Fujifilm GFX 100S or Phase One iXH cameras depending on the type and needs of the herbarium sheet. The image also displays components including a ruler and colour chart to the right of the herbarium sheet, a standard practice in digitisation to quality assure colour, resolution and focus. Digitisation officers use Capture One software when imaging, and Kew has also created a custom style through this software which is applied to each image. You can see more of this in action when the project was covered by BBC news last year. An important aspect of the digitisation project is that each sheet with specimen material (including illustrations, photographs and cibachromes) must be barcoded with a catalogue number and a record created on the ICMS database with storage, occurrence and collection event information transcribed. On the data portal, users can search directly for the corresponding record and image if available (records are continually being added as the project progresses), appearing as so:

Wisteria specimens in the herbarium are mounted on what Kew refers to as “standard sheets” and therefore were first digitised by the project’s imaging supplier. In terms of the project’s current in-house workflow, palms and pandans, new acquisitions, and more complex specimens throughout the main collection are left to be completed now that the project is in its final stages.

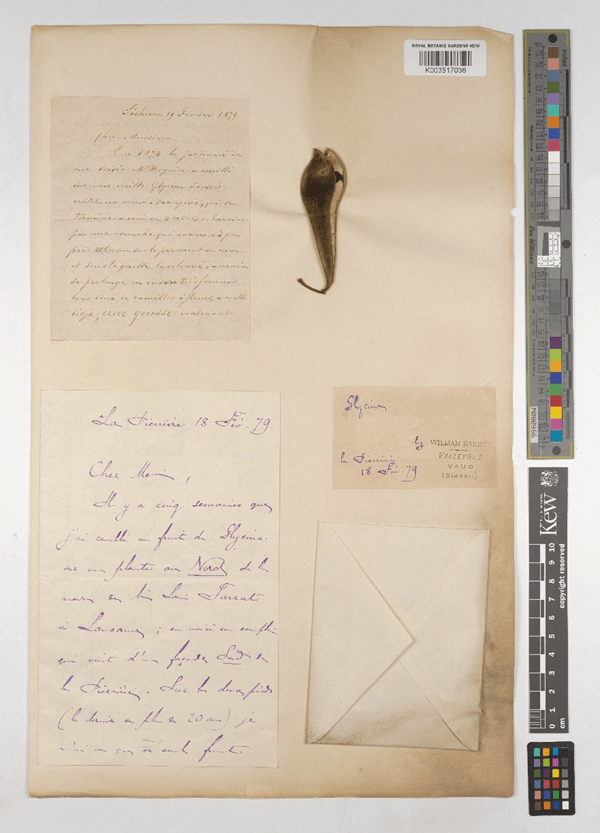

The second specimen shows a different species, Wisteria sinensis, but also shows a different aspect of the plant (see image 3). Wisteria are in the legume family, and as well as the blue-purple flowers, produces toxic seed pods/fruit. On this sheet, the collector, William Barbey, a Swiss botanist, details in a letter that he has collected fruit from a Glycine plant, a synonym of Wisteria, five weeks ago. Whilst not showing the same parts of the plant and therefore we can’t compare the characteristics of the flower to the first specimen, here we gain a new perspective on plant by Barbey’s collection of the seed pods. The label written by Barbey unfortunately is unclear on the collection locality, attributed in Kew’s collection to the East Asian region. However, by digitising the sheet and making it available for the public, students and researchers, these new deductions and analyses could be made, and this is ultimately one of the most significant benefits of digitising.

Alternative Perspectives Through Botanical Illustrations

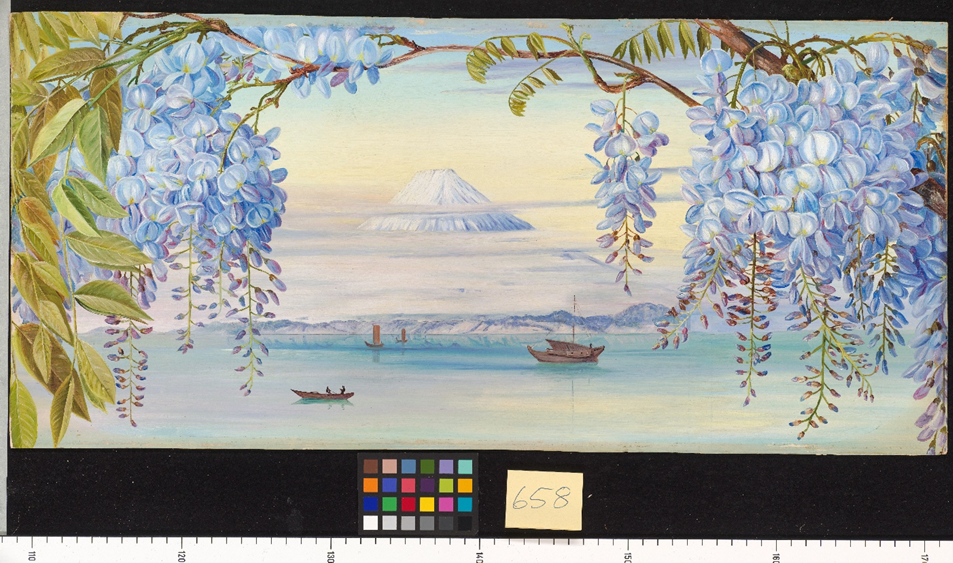

Botanical illustrations hold an important role in Kew’s collection and provide useful illustrations of a plant’s visual characteristics which may not be possible to capture through photography alone. Historical illustrations also provide further context to the work of botanists and plant collectors of the past, sometimes even being attributed as an original depiction of a specimen in lieu of the physical specimen. In the case of biologist and botanical illustrator, Marianne North, her travels around the world exposed her to many species, some of which were new to science and have been named in her honour, such as Crinum northiana and Nepenthes northiana. North travelled to Japan for a short time in the mid-1870s, depicting the landscape and everyday life. She had hoped to stay for a number of months, but developed rheumatism and moved on to Singapore to recover. While she was in Japan, she wrote to Kew’s founder, Joseph Dalton Hooker, about Japanese bonsai and bamboo, and painted several landscapes. Below (see image 4) is her painting of Wisteria chinensis from this time, and her artistic interpretation gives a different perspective to the herbarium sheets above. Her illustration shows the key characteristics of the plant and colours of its flowers, but additionally alludes to a fascinating observation. Here, the wisteria flowers or fuji in Japanese, are framing Mount Fuji, an iconic symbol of Japan, and often linked to wisteria as they share the same name.

A second botanical illustrator I’d like to highlight is Iwasaki Tsunemasa or Iwasaki Kan’nen (1786-1842), a botanist and entomologist, who was active during the Tokugawa shogunate in the early to mid-nineteenth century. In his collected volumes of botanical illustrations titled Honzo Zufu, Kan’nen depicts many native and foreign plants to Japan, including the wisteria sinensis (see image 5). The Honzo Zufu was digitised in a separate project to the current digitisation project, and this also involved careful conservation work to address binding issues and prevent future damage to many of the volumes. You can see in Kan’nen’s illustration a very different interpretation to North. He uses a darker colour palette and minimal background, as well as not including the woody branches, instead placing focus on the purple flowers. The two illustrations complement each other, and also demonstrates cultural differences in the practice of botanical illustrations and their purpose in the nineteenth century.

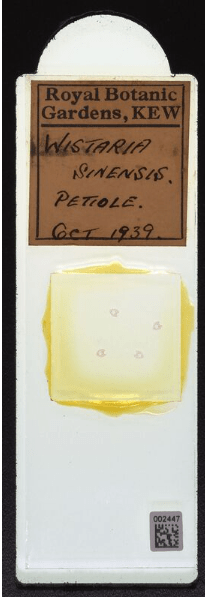

Digitisation of Microscope Slides

The digitisation team at Kew very kindly digitised several microscope slides of wisteria specimens to use in this article some of which you can see below (see images 6, 7 8 and 9). The microscope slides have a more complex imaging process completed by a specialist digitisation officer. It involves taking an image of the complete slide and then other high-quality magnified images of the specimen are captured against a backdrop of brightfield illumination with a ZEISS Axio Scan.Z1 microscope. Minor corrections are then applied to these images, and a scale bar is added for scientific representation. In comparison to the images so far included in my article, these images are yet another perspective, which show new dimensions of the plant only made possible through microscopic imaging techniques. This is perhaps previously the least accessible perspective of botanic study for both researchers and the public. In combination with the other forms of herbarium specimens in the collection, allows users to both focus in on, and widen, their examination of Kew’s specimens. The textures and colours are beautiful and diverse, contrasting to the dried mounted specimen. I can even anticipate that beyond their scientific and historic value, these images could be used as inspiration in art and design – connecting the sciences and arts through digitisation.

Conclusions

The comparisons and cross-referencing between species and mediums throughout this article were only made possible by the digitisation efforts at Kew, and the ongoing work to make accessible the entire collection on a digital platform designed for global collaboration and research. As I have demonstrated, digitisation shows possibilities for storytelling utilising different perspectives of the same genus or species. It can allow the reconstruction of past narratives and the reimaging of new stories using the collection, as well as serving to conserve Kew’s rich collection of biodiversity for the future. The Japanese collection at Kew, beyond the herbarium too, is extensive and there are still many stories left to tell, with this article only being a snapshot into the possibilities for future discoveries.

References

Compton, James, A., and H. Walter Lack. “The Discovery, Naming and Typification of Wisteria floribunda and W. brachybotrys (Fabaceae) with Notes on Associated Names”. Willdenowia 42, no.2 (2012), pp.219-240.

North, Marianne. Letter from Ms Marianne North to Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker; from ‘between Japan and China’; 18 Jan c.1875. Directors’ Correspondence 151/842, Page 1 of 4. https://plants.jstor.org/stable/10.5555/al.ap.visual.kdcas4435

Whittaker, Ashleigh, and Sarah Phillips. “Digitising Kew’s Science Collections: Upscaling and Delivering at Pace”. Biodiversity Information Science and Standards 8 (2024), pp.1-3.

Editors note (October 23, 2025): This article has been revised since its original publication.

2 thoughts on “Digital Storytelling in the Digitisation of Japanese Botanical Specimens in RBG, Kew’s Collections”