This is a guest post by Aizat Ishembieva.

The National Museum of Denmark houses one of the most significant 19th-century Central Asian ethnographic collections—”The Olufsen Collection.” In the Olufsen Collection, there are approximately 700 objects from Russian Turkestan, Emirate of Bukhara, and Khanate of Khiva; an area that today consists of the independent states of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan.

Almost all objects originate from two Danish Pamir Expeditions in 1896-97 and 1898-99. They were collected as part of an exploration of Central Asia, and are accompanied by a comprehensive collection of written accounts and photos. As Fihl (2010, 2:668) notes regarding the collection’s distinct historical significance, “these objects form a coherent whole as they were collected by the same person, acquired in Central Asia between 1896 and 1899.”

These interdisciplinary expeditions sought to expand European knowledge of the Pamirs and adjacent territories, documenting their diverse cultural and environmental landscapes. Led by Premier Lieutenant Ole Olufsen (1865–1929) and his team, the expeditions made a remarkable contribution to the study of the region’s geography, ethnography, and natural sciences—just before the profound transformations of Central Asia in the early twentieth century. At the time of the Danish expedition’s visit, the region had remained relatively isolated and thus largely untouched by the sweeping changes of a new era in world history. Ole Olufsen (1911, 22) himself observed, “…In a way it must be regretted that this country which is so interesting will by degrees be deprived of its old-fashioned Oriental character, and like the many other visitors to Bokhara I am happy in having seen all the peculiarities of the country while it and its people are still the same as in the days of Tamerlan…”

Fotografi Olufsen (Photo of Ole Olufsen). The Royal Danish Geographical Society – January 1, 1910 – January 1, 1930. This black-and-white slide (5×5 cm), stored in a cardboard box marked “G.S. 90 år” comes from the Royal Danish Geographical Society’s archive, housed at the National Museum since 2010 and administered by the Ethnographic Collection.

Expedition Routes and Collection Methodology

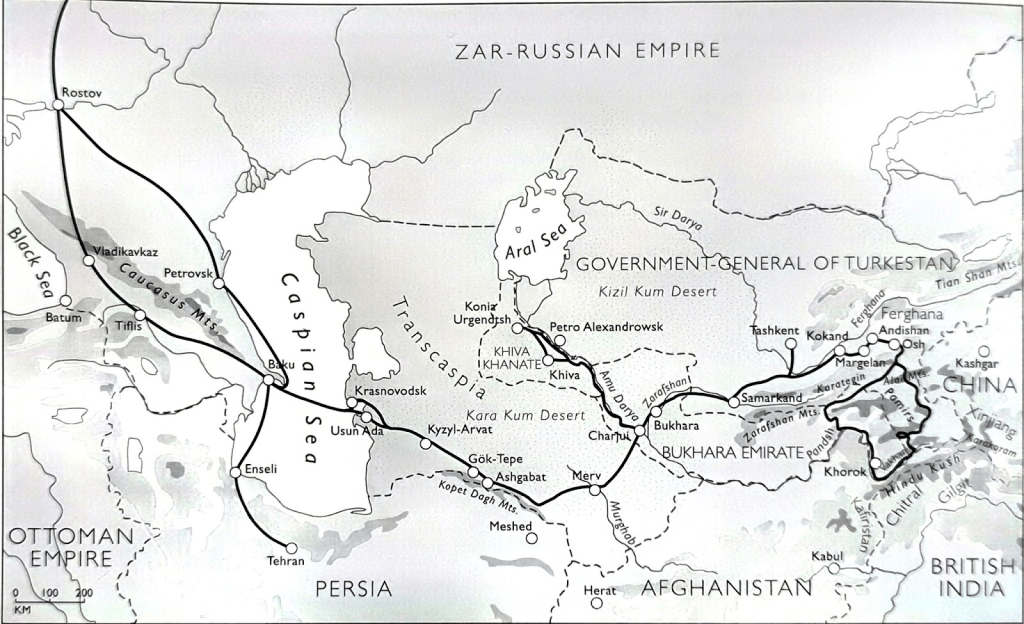

The expedition route stretched from the harbor of Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan) on the Caspian Sea to the Pamirski Post (Murgab, Tajikistan) in the eastern Pamir. Esther Fihl describes the extraordinary scale and difficulty of Olufsen’s expeditions, underscoring the vast geographical scope of the resulting collection (2010, 1:29):

“The distance is approximately 2000 km as the crow flies, but in the often trackless country it may be estimated that the round trip in Central Asia of the expedition can scarcely have been less than 6000 km. The area contains different climatic zones, with fertile oases along the rivers and wide expanses of steppe with adjacent desert. To the east rises the enormous Pamir Mountain massif, and in the west, certain areas like the Caspian Sea lie below sea level.”

Travel route of two Danish Pamir expeditions through Central Asia. By Jorgen Muhrman-Lund. Image taken from Fihl (2010, 110).

Olufsen and Philipsen travelling through the steppes of West Turkestan. Photographer: Ole Olufsen. Source: National Museum of Denmark (1896).

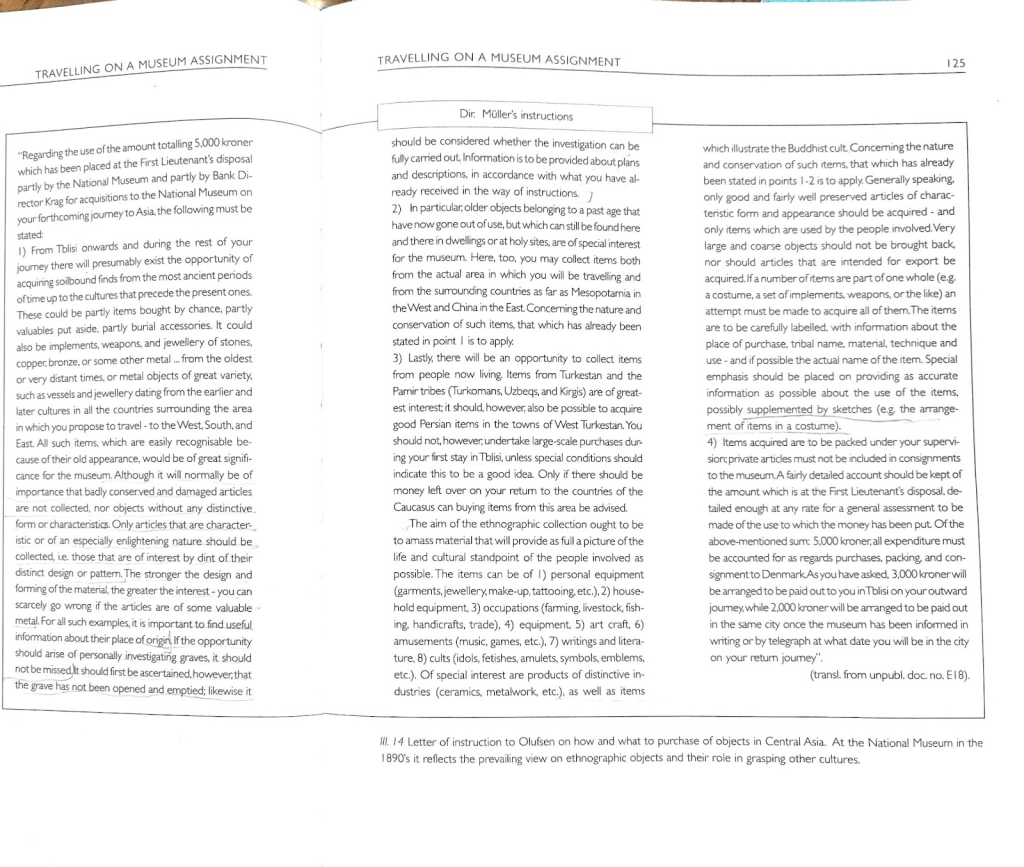

Olufsen’s collecting strategy was closely aligned with the direction of the Danish Ethnographic Museum, which was one of the main sponsors of his expeditions. Before his departure, he received detailed written instructions from Sophus Müller, Director of the National Museum. Müller emphasized the importance of collecting across a broad geographical area to ensure cultural diversity and include representations of various social groups including nomadic, semi-nomadic, pastoralists, semi-agro-pastoralists, and urban populations.

Following closely these guidelines, Olufsen categorized his objects into five major cultural-geographical areas:

- “Bukhara and Turkestan” (the courtly and urban culture of the Bukharan Emirate and the Russian-controlled part of Turkestan

- “Kirgis in Pamir” (Kyrgyz nomads in Pamir)

- “Vakhan” (semi-agropastoralists)

- “The Turkomans in Transkaspia” (nomadic and settled Turkmen)

- “The Khanate of Khiva” (urban craftsmen and traders)

Instructions by Olufsen on categorising objects, reproduced in English by Esther Fihl. Image taken from Fihl (2010, 124).

Fihl (2010, I:135) notes that Olufsen’s inventories divided the collected objects under headings corresponding to these regions. This organizational structure continues to influence how the collection is understood and accessed today, illustrating how early categorization decisions can persist through generations of curatorial practice and into digital systems.

Registration History and Digital Update

The Collection represents a wide range of material culture, including clothing and personal accessories, jewelry, weapons, a tent, household utensils, musical and signal instruments, and equestrian equipment. Tracing how these objects have been registered and re-registered over time can be useful for understanding the evolution of museum documentation and its impact on digital accessibility.

All artifacts collected during the Danish Pamir Expeditions (1896–1897 and 1898–1899) were initially recorded by Ole Olufsen into List I and List II, respectively. Upon returning to Denmark, the initial numbering system was replaced: objects from the first expedition were registered in Q-Protokol A 1896, and those from the second expedition were registered in Q-Protokol A 1899 (Fihl 2010, I:179). Each object was assigned a “Q” letter followed by a running number, providing a standardized system for recording.

The first page of Olufsen’s Liste / with his information on the purchased items from 1896-97. (Photo: Blædel, 1999. Archives of the National Museum, Copenhagen.” Image taken from Fihl (2010, 176).

By around 1930, the artifacts in the Olufsen Collection underwent a thorough revision, resulting in extensive draft lists documenting missing or unidentified museum objects. In addition, a comparative list was compiled to identify discrepancies between the physical items in the museum and their entries in the original Q-Protokol A. This process led to the creation of a new, systematic registration and renumbering of the collection, which formed the basis for the catalogues Q-Protokol Q.1–453 and Q.454 (Fihl 2010, I:179). In 1991, this registration was slightly revised and digitized without altering the underlying visual identification criteria, and fully incorporated into a computer-based database alongside other parts of the Ethnographic Collection (Fihl 2010, I:181).

Today, objects from the collection are registered (including digital database) as Q1–Q187 (the first expedition) and Q188–Q431 (the second expedition). These Q-numbers often include subdivisions (e.g., Q2a–n) to represent complex sets such as complete men’s and women’s costumes or equestrian gear, a tent and household utensils etc. As Fihl (2002, I:135) highlights, the collection includes thirteen costumes (summer and winter), a qalandar’s outfit, headdresses, footwear, and four full equestrian equipment sets, many of which are characterized as complete or nearly complete.

Further acquisitions related to Central Asia were also incorporated into the collection up to number Q543. These later additions to the museum’s collection, acquired between 1916 and 2018, represent a range of various acquisition types, including purchases (e.g., Q432–Q440, Q450–Q453), gifts (e.g., Q442–Q445, Q479–Q481, Q495–Q501), and inheritances (e.g., Q503). Some inherited items were originally collected by other participants in the Danish Pamir expeditions, such as Ove Paulsen and Anthon Hjuler. Several entries—particularly those in the Q500–Q543 range—comprise materials linked to the expeditions but accessioned much later, often through donations from descendants. However, not all of these objects were collected by Ole Olufsen or his contemporaries; some were added to the collection at a later date and originate from unrelated sources.

Digital Access and Considerations

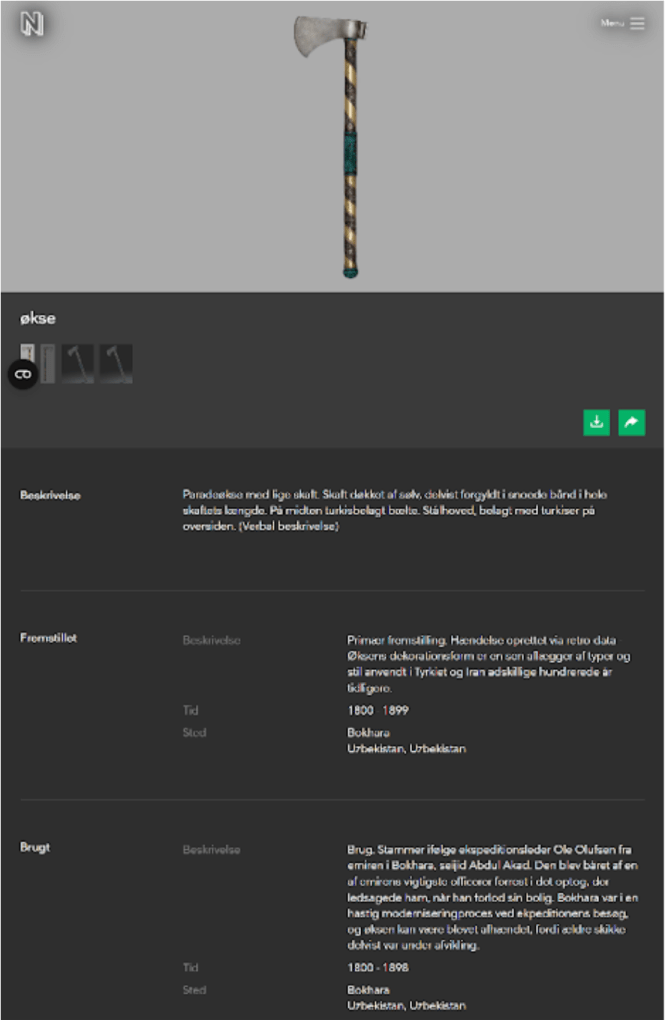

The Olufsen Collection can be accessed through two main resources: the re-examined and expanded catalogue published by Esther Fihl (2010), and the National Museum’s online digital database. The online database presents information about the Olufsen collection in Danish and preserves many of the features of the original curatorial record. The digital entries include the name of each object, measurements, and a short description provided by Ole Olufsen himself, sometimes incorporating his verbal description when available. Provenance details are also provided, including the place of manufacture and the approximate period in which the object was made, both drawn from Olufsen’s original notes (see an example of an archive entry below).

Økse Q.292 (The ceremonial axe (Fihl 2010, 574), “Tabar -balta” (Miloserdov.162, 2019) from Bukhara, as described in Olufsen’s account, holds deep cultural and symbolic significance. It was not a functional weapon but a marker of status and authority, carried by high-ranking officials in public ceremonies (Olufsen 1911, 477). The screenshot is cropped; for the complete record, please follow the link.

Acquisition data is included, specifying funding sources, donor names (if applicable), and, where possible, an accession date. In certain instances, the records also include a note indicating Olufsen’s involvement in the registration and description of the objects following his return; an example of this can also be seen in the case of the felt tent series presented at the end of this post. The database further lists the object ID, the materials from which it was made, colour, and measurements taken by the museum staff at the time of accession or during later cataloguing.

The strength of the online database lies in its ability to preserve the original archival structure and language. For researchers concerned with the “museum life” of an object—its history within the institution—this retention of original data is of considerable value. However, the limitations are equally clear: entries are often brief, context is minimal, and visual documentation is inconsistent, with only a small proportion of objects illustrated.

The online database itself, while searchable, offers limited filter options. It is recommended that users seeking objects from both Danish Pamir expeditions use specific search terms such as Q.-number to locate relevant materials efficiently. These limitations highlight common challenges in museum digitization efforts, where cataloging systems designed for internal use may not fully accommodate the needs of external users. We can also use the names of regions as search keywords when navigating the digital database. While these names can serve as helpful search tips in the database, users should be aware that the categorization is not always consistent: not all objects labeled under a specific region necessarily belong to it, and sometimes unrelated objects are included as well.

Interestingly, the digital database continues to reflect Olufsen’s original five cultural-geographical categories, which can create tension between historical and contemporary understandings of the region’s cultural boundaries. Moreover, the modern online inventory assigns place of provenance according to Olufsen’s original List I and II, but sometimes updates locality names based on contemporary geography. For example, object Q2d is recorded as originating from Osh Sart, Kyrgyzstan, whereas in Olufsen’s original list is noted under Osh, referring to the region controlled by the Bukharan Emirate and Russian Turkestan (Fihl 2002, II:477).

Conclusion

Today, the Olufsen Collection stands as a remarkable example of how nineteenth-century ethnographic expeditions continue to shape contemporary understandings of Central Asian culture. Collected across a vast region—from the Caspian steppes of Transcaspia to the high mountain valleys of the Pamirs—the collection reflects an extraordinary geographical and cultural range. With nearly seven hundred artefacts representing nomadic, semi-nomadic, and urban communities, it offers a rare and coherent ethnographic portrait of Central Asia at the turn of the twentieth century. The richness of this collection lies not only in its variety of material types—costumes, jewelry, weapons, household utensils, and equestrian gear—but also in its layered documentation: from Olufsen’s meticulous field notes and lists to the Q-Protokol registration system, later revisions, and eventually digital records.

What began as a scientific and ethnographic enterprise—rooted in the classificatory and hierarchical logic of European knowledge—has evolved into a digital archive that both preserves and reinterprets nineteenth-century epistemologies. Through the collection’s successive transformations—from field lists and handwritten protocols to modern metadata and online databases—we can trace the enduring influence of museum systems that sought to order cultural difference through material form (Penny, 2003; Fihl, 2010). Yet, the act of digitization is not a neutral translation of analogue data into pixels. It constitutes a new curatorial gesture that determines how the past becomes knowable in the present. The persistence of Olufsen’s original categories in the digital database exemplifies how nineteenth-century modes of seeing and classifying continue to structure digital access, shaping what is visible, searchable, and narratable.

Part 2 will look at how Esther Fihl’s expanded catalogue and re-examination of the Olufsen Collection offer an important counterpart to its digital presence, addressing some of the gaps in the National Museum’s online database.

References

Esther Fihl, Exploring Central Asia: From the steppes to the high Pamirs, 1896–1899, 2 vols. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010; originally published 2002, Thames & Hudson/Rhodos).

Dmitry Miloserdov, “Arms and armor of Khanates Central Asia (Bukhara, Kokand, Khiva) of the late 18th – early 20th centuries,” Оружие и Доспехи в Ханствах Средней Азии (Бухара, Коканд, Хива) Конца XVIII – Начала XX в. (2023).

Ole Olufsen, Through the unknown Pamirs: The Second Danish Pamir Expedition, 1898–99 (London: William Heinemann, 1904).

Ole Olufsen, The Second Danish Pamir-Expedition: Old and new architecture in Khiva, Bokhara, and Turkestan (Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, 1904).

Ole Olufsen, The Emir of Bokhara and his country: Journeys and studies in Bokhara (with a chapter on my voyage on the Amu Darya to Khiva) (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1911).

H. Glenn Penny, Objects of culture: Ethnology and ethnographic museums in imperial Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

One thought on “The Olufsen Collection: From 19th-Century Expeditions to Digital Museum Collection – Part 1”