I recently started working at the National Institutes for the Humanities (NIHU). When I was preparing for my move to the post, I began exploring some of the tools that the organization has developed. One in particular surprised me, the Resource Guide for Japanese Studies and Humanities in Japan. As the name suggests, it is a repository of different resources for Japanese studies. A simple initiative, which I had not yet come across in my journey in Japanese studies. The Resource Guide is a little different to the sort of repositories for Japanese studies we have before. Japan Search—which I have been both critical of and subsequently reassessed—for example gives access to materials (texts, images, videos etc.) from different resource providers within a single portal, this list however gives access only to the different projects of which there are 481 currently listed. This article (re-)introduces readers to the Resource Guide and provide a brief introduction to its features.

The first thing that a use of the Resource Guide might notice is that its introduction is a little confusing. Its description says that it is “a collection of links to useful English websites and resources pertaining to Japanese studies and humanities in Japan,” but for the most part it is actually a list of links to Japanese websites. The Resource Guide itself is mostly in English with English menu titles, and a lot of the entries containing English descriptions and sometimes translated English titles as well, yet some entries also usually contain Japanese titles and sometimes Japanese descriptions as well. The original aims of the project when was started in 2013-2014 was that of having a “English Resource Guide for Japanese Studies and Humanities in Japan,” as a means to promote the globalization of Japanese studies and make these resources available to other audiences. Right now, there is no option to change the language into Japanese, which might expand the audience to other non-English speaking audiences. Whether such an update can be expected is unclear. The copyright mark at the bottom of the page lists 2019, which might indicate that the Guide is no longer actively updated.

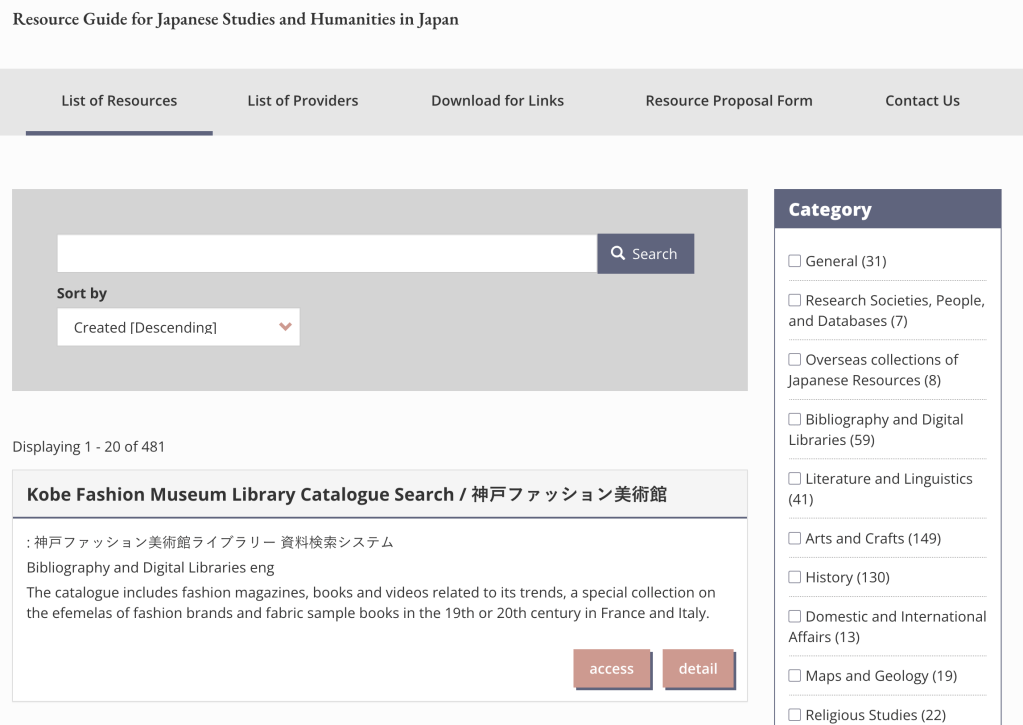

The user has the choice to navigate according to pre-defined categories from the main page, conduct a simple keyword search, or view the full list of resources. The website also purports to offer a list of providers, but at the time of writing, this menu did not work. An interesting feature is that all resource links and their metadata can be downloaded in CSV or XML format. This is something I would like to see in other repositories and lists, since it allows the data to be studied and scrutinized by interested parties, and saved by users in case the platform is ever shut down. Other menu items include a form that allow users and institutions to propose resources for inclusion.

Screenshot of the Resource Guide after clicking on the “List of Resources” tab.

The Guide contains 11 categories with most resources being found in the sections of Arts and Crafts (149 resources), History (130 resources), or Bibliography and Digital Libraries (59 resources). The resources listed are hugely varied. I was surprised to find that there were digital projects within my own research area (even when quite narrowly defined) that I had missed. For example, Meiji Gakuin University Library’s digital archive of Japanese translations of the Bible or the digital archives of the Church of the Nazarene Japan. Continuing to focus on some examples from religious studies, the list includes major projects such as the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, older projects that no longer appear to be receiving ongoing support such as Kokugakuin University’s “Establishment of a National Learning Institute for the Dissemination of Research on Shinto and Japanese Culture” project, and projects of local interest such as Okayama Prefecture’s mapping of shrines. What positively surprised me was the sheer volume of projects that I have somehow missed despite having a fairly good knowledge of Japanese digital resources for Japanese studies. I imagine that this is due to the inclusion of many smaller, locally-focused, and older projects.

The Guide’s categories.

There is nothing particularly revolutionary about the Resource Guide itself—it functions well and is accessible to English speakers—but it will be clear to any visitor that there are a huge array of digital projects that we often overlook or miss. As such, I really urge readers to try exploring the Resource Guide for Japanese Studies and Humanities in Japan to see what projects you may have missed and how these may inspire, shape, or inform your ongoing work and studies.

2 thoughts on “The Resource Guide for Japanese Studies and Humanities in Japan: A Brief (Re-?)Introduction”