The field of Syriac Digital Humanities continues to advance rapidly, moving from basic text recognition (as discussed in my previous posts on OCR/HTR, particularly our launch of the first public Syriac HTR model on Transkribus: From Vienna to the World…) into the realm of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Today’s post explores a powerful new possibility: using AI image models to generate visual reconstructions of damaged Syriac manuscripts and fragments.

The Power of AI for Manuscript Visualization

Traditional manuscript study is often hampered by the physical condition of the primary sources. Ink bleed, physical damage, and fragmentary nature can obscure crucial text and prevent scholars from appreciating the original appearance of a manuscript page.

Generative AI offers a novel solution:

- Visual Reconstruction: By providing an AI image model with the transcribed text of a damaged page, we can prompt the engine to create a high-quality, clean image of how the manuscript would have looked before degradation. This provides a clearer, more readable reference image for study.

- Completing Fragments: This technique is especially useful for fragmented sources, such as those addressed by my ongoing FWF project, “Identifying Scattered Puzzles of Syriac Liturgy Manuscripts and Fragments” (ISP). By supplying the known or reconstructed text for the missing portions, the AI can generate an image of the completed page, allowing us to better visualize the original format and layout.

While these results are artificial images, they serve as invaluable aids to imagination and hypotheses, helping scholars envision the full structure of the original document.

The Case for Caution: The Forgery Risk!

The ability to generate highly realistic, stylized images of ancient manuscripts, however, carries a profound ethical obligation that must be clearly addressed:

- The Forgery Threat: The same technology that allows scholars to reconstruct images could easily be exploited by forgers. Generating convincing, artificially aged manuscript fragments and pages is now technologically feasible, posing a significant risk to the authenticity of manuscripts sold on the black market.

- Need for Clear Labeling: It is absolutely essential that any AI-generated image used in academic research or publication be prominently and permanently labeled as an “AI Reconstruction” or “Artificial Image.” These images must be treated solely as interpretive models, never as primary evidence.

Case Study 1: Reconstructing the Syriac New Testament (ÖNB Cod. Syr. 4)

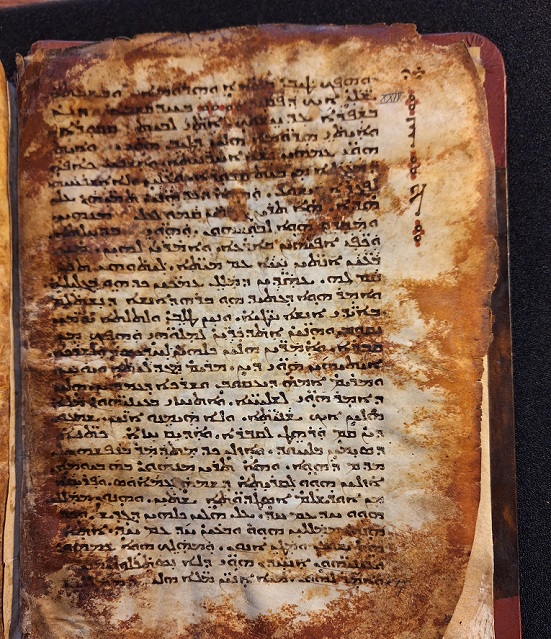

To demonstrate the power and precision of this method, I undertook an experiment using a partially damaged Syriac New Testament manuscript from the Austrian National Library: ÖNB Cod. Syr. 4. The original page is heavily compromised by deterioration, making portions difficult to read.

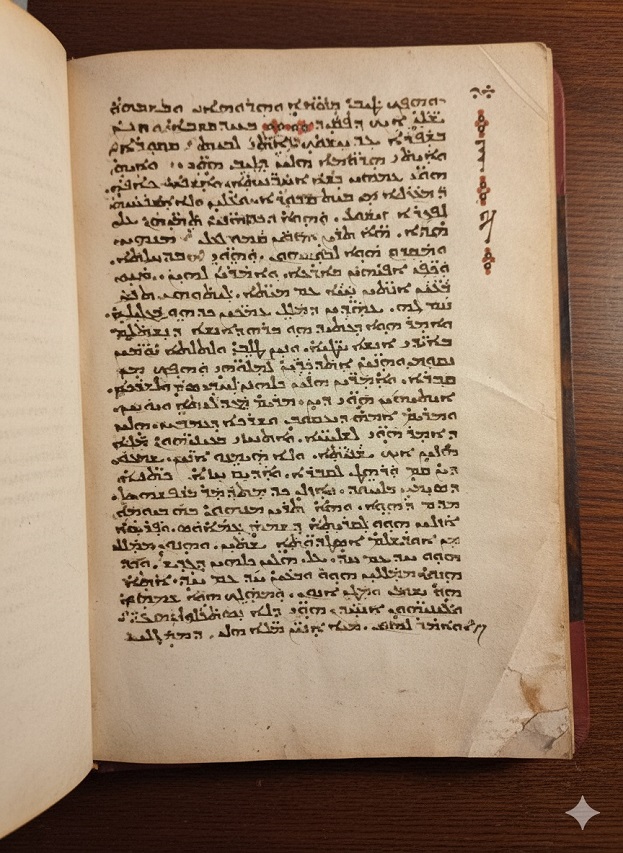

The Original Document vs. AI Reconstruction

Below, the challenging condition of the original page is clear, showing significant damage from deterioration. Next is the AI-generated reconstruction, which restores the clarity and original aesthetics of the manuscript.

Original image of ÖNB Cod. Syr. 4, showing heavy deterioration.

AI Reconstruction of ÖNB Cod. Syr. 4, clearly rendering the text and original layout.

The Reconstruction Process

- Transcription and Completion: The first step involved providing the AI (Gemini) with the complete, correct text for the damaged page. I used our dataset of the Syriac Peshitta New Testament (Vienna Syriac Gospels – Moses of Mardin 1554) to reconstruct the obscured text, ensuring the words matched the visible fragments on the page.

- AI Communication: After several rounds of iterative communication with the AI, the engine was able to generate a synthesized image based on the provided text, font, and layout.

- The Result: The final output was remarkable, producing a clear, readable page that faithfully recreates the original appearance.

Infographic of the Reconstruction Process.

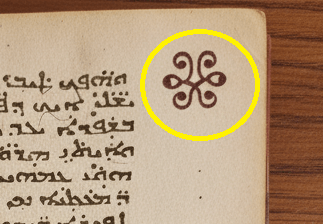

Overcoming the Quadruple-Dots Mark

The main obstacle encountered during this process involved a small, yet significant, marginal symbol: the “quadruple-dots mark” (often found in the top-right corner of the verso page).

This mark, which can take the form of four dots arranged in a lozenge or a stylized abbreviation of the divine name (ܞ) in the East Syriac tradition, often served a liturgical or practical function, such as marking the beginning of a new work (see, P. Borbone’s argument in COMSt book 2015, p 257, here).

My solution to ensure the AI accurately rendered this symbol in its precise marginal location was pragmatic: after several failed attempts to describe the symbol and its vertical orientation in the margin, I cut and pasted a sample of the mark from the original damaged image. The AI successfully interpreted this input, regenerating the symbol with clarity and correct positioning, effectively utilizing a Photoshop-like technique to perfect the final image.

Marginal symbol: the “quadruple-dots mark” (original).

AI Generated Image 1.

AI Generated Image 2.

AI Generated Image 3.

AI Generated Image 4 final.

This case study proves that generative AI, when guided by expert human transcription and innovative communication techniques, can become a critical tool for preserving the legibility of our most damaged Syriac written heritage.

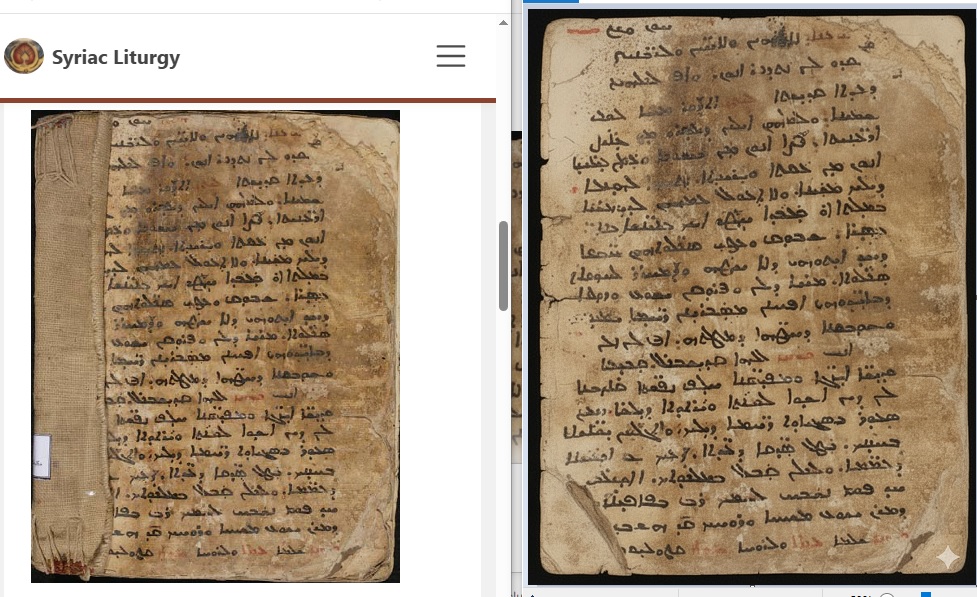

Case Study 2: Visualizing In-Situ Binding Fragments (Aleppo N. 232)

A second, more challenging case study highlights the AI’s potential in manuscript reconstruction and visualization. This involves the in-situ binding fragments of Aleppo N. 232 (SOAA 0232), which were repurposed as the front and back covers for another manuscript. The context of the original codex was destroyed when the pages were used as binding material.

These fragments provide an interesting puzzle:

- Front Cover: A paper fragment written in Serto script, dating approximately to the 16th–18th century. The text was identified as being from the Syriac Anaphora of Bar Salibi.

- Back Cover: A second fragment from the same original manuscript of the Front Cover. The content was identified as a text from the Syriac Anaphora of St. Basil of Caesarea.

The challenge here was to use the known text to visualize the fragments as complete, flat pages before they were cut, folded, and attached to the binding.

Visualizing the Reconstructed Fragments

The images below demonstrate the AI’s ability to visualize the original form of the fragments, transitioning from the damaged, bound context to clean, flat, and somehow complete manuscript pages.

Aleppo N. 232 Back Cover fragment (left) in its current state as a binding material, contrasted with the AI reconstruction (right) visualizing the completed page.

The Visualization Goal

Using the reconstructed text provided from the ISP project dataset, we prompted the AI to generate images of the fragments as clean, flat, and complete manuscript pages.

The AI successfully generated these clean images, providing a crucial visual aid for scholars attempting to understand the original folio layout and aesthetic of these repurposed pages. This demonstrates that generative AI can move beyond simple cleanup; it can become a powerful tool for visualizing the object’s original form, which is indispensable for fragments whose primary context (the original codex) is entirely lost.

For more about these fragments, see ISP New Findings: Aleppo N. 232 here and here.

HTR and AI: A Digital Ecosystem

This new development in generative AI complements our previous work on Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR), such as the public Syriac model we released on Transkribus (see the report of the HTR Winter School 2024, here):

- HTR Provides the Input: Accurate HTR (or human transcription) is the foundation for this process, as the AI needs reliable text to generate the image. The cleaner the text input, the better the visual output.

- AI Provides the Visual Output: AI transforms the data (the text) back into the visual form (the manuscript), creating a circle in the digital preservation process.

As we continue to develop these Artificial Intelligence tools for Syriac, the ultimate goal remains the same: to expand access to our heritage. However, the advancement of these powerful tools necessitates a corresponding increase in our Human Intelligence—specifically, in our ethical oversight and methodological caution—to protect the integrity of Syriac scholarship.

Poster presented at the “AI Meets Humanities” conference (ÖAW, Vienna, June 2025), announcing the first public Syriac HTR model on Transkribus.

References

Eirini Afentoulidou et al., “Winter School of HTR of Medieval Documents 2024 – Growth and Vision for the Future,” Historical Identity Research Blog (2025).

Alessandro Bassi et al. (eds.), Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction (Hamburg: Tredition, 2015).

One thought on “Syriac AI Manuscripts and Fragments: Reimagining Digitally the Damaged Past”