Those of us who use languages written in the Latin alphabet likely don’t think much about how we input text. On most devices, we use a physical or virtual keyboard likely, though not necessarily, in QWERTY layout. For languages not written in the Latin alphabet, we familiarize ourselves with other types of input as well. On my phone, I make use of both flick input for Japanese and Chinese handwritten input for example. Latin-based languages also have different forms of input: several friends make use of swipe input (sliding one’s finger from letter to letter on the virtual keyboard) when typing in English. Some of us will also remember alternative forms of input for Latin script on mobile phones such as the multi-tap text entry system, which was popular prior to the advent of smartphones.

In this article, I introduce chorded input and its application to Japanese. I explore what chorded input is, and why it might be particularly suitable for the Japanese language and learners of it.

When we type on a computer, we usually do so in a way that mimics typewriting—we press single keys in a sequential order to create words on our screens. Differently, chorded input draws on the traditions of stenography and technology such as the stenotype. It can take many forms and often requires specialist hardware and training, but the concept is simple—several keys are pressed simultaneously (like a chord on a piano) to create the desired output. Chording offers some advantages over typing when it comes to text input speed. However, it has a longer learning curve, hence it has not been widely adopted.

In recent years efforts have been made to increase the accessibility of chording by making it possible to chord on QWERTY keyboards. One example of this is the CharaChorder Lite. In research that I conducted alongside Markus Rude, Anubhuti Chauhan, and Hiroaki Hatano, I used a bespoke web application to be able to chord Japanese on QWERTY keyboards. The web application only outputs kana.

Figure 1: CharaChorder One, an example of a Chorded Keyboard. Image from WikiMedia CC BY-SA 4.0.

The system that we developed for Japanese involves chording based on moraic units. For example, the word for Japan is nihon 日本 and it consists of three moras: ni に, ho ほ, and n ん. If we type this word using traditional typing methods we have to press five keys (the Latin letters n i h o and n) in the correct sequence, and the computer converts to the desired output following the user’s judgement. When chorded, however, the user needs to make only three chords—one representing each mora. The software (re-)arranges these simultaneous key presses (chords) into the correct order. In other words, the user may press “in” or “ni,” and the computer will recognize and provide the desired output of ni に. There are no other possible outputs in Japanese for this chord. The word nihon could therefore be input as “ni”+“ho”+“n,” “in”+“ho”+“n,” “ni”+“oh”+“n,” or “in”+“oh”+“n,” and the computer would correctly arrange it as the desired output. It is easier to develop software capable of doing this with Japanese than other languages because of the limited number of mora, and the lack of cross over between them. With a syllable-based language such as English there may be cases when a single chord would have multiple potential outputs. If I chorded “lge” the computer must decide whether I desire the output “leg” as in “legacy,” “gel” as in “gelatine” or “gle” as in “eagle.” As such English and other languages require much more sophisticated software.

But when it comes to Japanese, there are a few reasons why we might be interested in using chording. Preliminary experiments in our afore noted research have shown that chording can achieve higher speeds than typing without negatively affecting accuracy. Furthermore, we were able to demonstrate that learning to chord on a QWERTY keyboard and gaining this speed advantage could be achieved with very little training. There is then a theoretical advantage (so far, we have not been able to demonstrate this within our research) is a decrease in errors within single moras. In the example of nihon, if I accidentally input “in” rather than “ni” on my keyboard, the computer will input in and I will need to fix this error manually. With chording, the computer automatically recognises the error and corrects it to “ni,” which is the only possible mora for this chord. This is why chording reduces the overall input time. Because the chording systems automatically correct these inversion errors on the level of the mora, the overall time is shorter than hitting the keyboard six times when typing “in”, backspace twice to erase it (assuming the mistake is immediately noticed), and a further two to input it correctly. For chording, there is a single chord consisting of the simultaneous pressing of the keys “n” and “i.”

In addition to the above, there are potential advantages for Japanese language learners. In forthcoming work, we explore the relation between the rhythm of speaking and typing vs. speaking and chording, illustrating that chording allows computer users to achieve a rhythm that more closely matches the spoken language. The main advantage for language learners is that learners are able to think of Japanese linguistic units in terms of mora rather than in terms of groups of Latin letters. This may help with pronunciation and rhythm, particularly amongst early learners of Japanese.

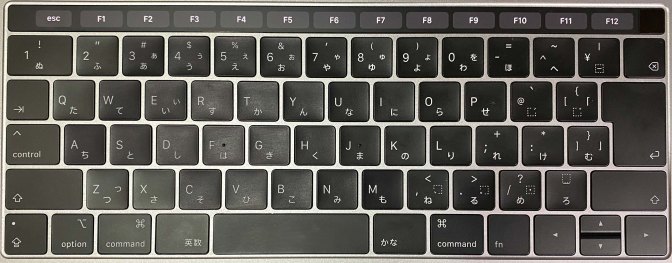

We are yet to trial the use of chording in the classroom, though this is an important next step for our research. Our system of chording allows learners to keep using their QWERTY keyboards (rather than having to learn new input methods) which also makes it an accessible form of text input for the classroom in comparison to using a JIS keyboard, which requires learning a whole new system of text input.

Figure 2: Example of a JIS keyboard. Image licensed under CC BY 4.0.

By focusing on the topic of chording here, I hope I have been able to show its potential and suitability for use with Japanese. It must be noted that chorded input varies widely based on hardware and software usage. Through more collaborative research, we also hope to develop a desktop chorder that will allow users to output text in kanji, switch easily between typing and chording, and gain the advantages of the aforenoted chording auto-correction. Preliminary experiments have shown all of these things to be achievable. If you’re interested in reading our preliminary findings on chording in Japanese please see the papers linked below, and if you’re interested in collaborating with us (particularly if you have developing or programming skills) please feel free to reach out to the author or by leaving a comment below.

Further Reading:

Rude, Markus, et al. “Chording Needs Training? Potential and Challenges of Moraic and Syllabic Typing for Language Learners and Everyday Users,” Studies in Foreign Language Education 45 (2023): 21-39.

Rude, Markus, et al. “Browser-based Chording for Japanese on QWERTY Keyboards: Investigating Speed Advantage and Accuracy,” Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies 17 (2025): 107-138.

Cover Image: “MacBook Pro Touchbar JIS keyboard” licensed under CC BY 4.0.