Scholars working in the field of Korean studies have seen remarkable transformations in the way historical research is conducted. The emergence of innovative digital tools and platforms has provided new avenues for exploration and analysis of textual sources. Because digitized and open-access materials are widely available for the premodern Korean corpus, it is fairly easy to access texts online. Since premodern Korean texts were written with Chinese characters, Koreanists stand to benefit greatly from the digital platforms that have been created for use by sinologists. Among these tools is MARKUS, a digital text annotation and analysis platform developed to automate the markup of texts written in classical Chinese.

Briefly, MARKUS simplifies named entity markup in classical Chinese. Users upload a text to MARKUS and choose from different markup options. “Automated markup” uses built-in models for personal names, place names, temporal references, and official titles, linked to authoritative databases for accuracy. Users can opt for “manual markup” for more control or use “keyword markup” for custom keyword or regular expression-based identification. Users can switch between these modes for flexibility via the hidden side menu. MARKUS also allows exporting to websites like COMPARATIVUS, DOCUSKY, Palladio, and Gephi which offer other digital analysis tools. Gephi, for example, converts annotated text data into network visualizations, offering a visual representation of the relationships between entities – a useful tool when working with large amounts of data points. Lu Wang has reviewed MARKUS in depth elsewhere on the Digital Orientalist, this blog post will go over the features on MARKUS useful for Korean studies.

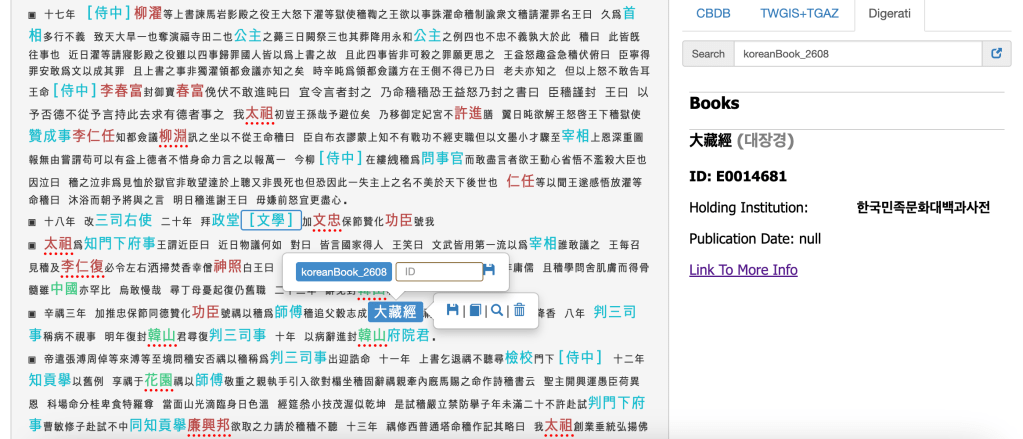

In 2019, the team behind MARKUS launched K-MARKUS for the markup of Korean texts written in classical Chinese. It automates the tagging and identification of Korean personal names, place names, official bureaucratic titles and posts, and book titles by default. This automation streamlines the annotation process, significantly reducing the time and effort required of a scholar to run textual analysis to scale. By integrating data sets from important Korean institutions such as the Academy of Korean Studies, the Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, and the Institute of Traditional Culture, MARKUS annotates texts quickly while also ensuring data accuracy. For Korean book titles, users can click on the mark-up differentiated book title and the metadata for that text will appear on the side menu with a link to the text’s entry in the Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. In the example below, the Korean Tripitaka has been identified and links to this page on the Encyclopedia. Of course, with any automated procedure, anachronisms will appear it is up to the user to clean up the markups of their document, which is easy to do in MARKUS.

Screenshot of MARKUS platform showing metadata and link for the Korean Tripitaka.

MARKUS has been thoughtfully structured so that information is easily accessed. Historical Korean place names are associated with their geographic location on an embedded map in the side menu and also linked to an external site in a separate tab labeled “Digerati.” The link takes you to the historical place as it is located on an important 19th century map called the Map of Dongyeo 東輿圖. This allows users to clearly identify both on a historical map and in modern-day space where any given place is. Since there are often place names associated with more than one location, each entity is given a unique id number listed in the side menu. These then link to specific locations on the Dongyeo map or are linked to entries in the Encyclopedia of Korean Culture in the cases where that historical place is not identified on the Dongyeo map. In the image below, the place name place name Yeonsan 燕山 is associated with three locations. The link above takes you to entity DYD_16_04_0246 (11072) on the Dongyeo map.

Screenshot of MARKUS platform showing metadata and links for three entities related to the historical Korean place name “Yeonsan.”

This integration provides scholars with access to a vast repository of pre-modern Korean data and texts within a single environment, eliminating the need to search through multiple sources manually. Such a range of data sets also empowers users to undertake comparative studies across different time periods, regions, or genres. The platform’s annotation and linked analysis tools enable researchers to identify patterns and connections within the complex historical and textual situation of premodern Korea. This is especially useful when one combines the datasets for Chinese and Korean mark up together. Though a bit unwieldy, the combined datasets support scholarship on the longstanding co-constitutive relationship between the Chinese and Korean states. Because MARKUS also allows for tailored ontologies, that is, customizable structured systems for categorizing and connecting tagged entities, users can adapt the platform to their specific research objectives.

For those working on premodern Korean texts, MARKUS is a valuable resource and fairly easy to use. Its comprehensive suite of tools and features help streamline the research process and simplify comparative studies and collaborative work. Whether an experienced digital humanist or a scholar first entering the field, this platform has the potential to enhance your engagement with pre-modern Korean textual sources and broaden the scope of your research.

One thought on “MARKUS for Korean studies”