This is a guest post by Christopher Francese, Asbury J. Clarke Professor of Classical Studies, Dickinson College francese@dickinson.edu

In 2016 I started assembling a team of students, scholars, and volunteers to digitize the Lexicon Magnum Latino-Sinicum (originally published in Macao in 1841, revised 1892, reprinted 1935) by the Portuguese missionary scholar Joachim Affonso Gonçalves. The finished product can be viewed and the data freely downloaded here. I had visited China for the first time in 2015, and met a number of scholars and students studying Western classical texts and reading Latin and Greek. Having overseen several smaller digitization projects (though never one involving Chinese), I wanted to provide Chinese-speaking Latinists with something like the resources enjoyed by English-speaking ones at sites like the Perseus Digital Library and Logeion. Like most digital projects, this one relied on the volunteer labor of many people. Many hands make light work, but also, in our case at least, inconsistent work. I reflect here about the process and its pitfalls, and solicit advice about how we might follow up on, and extend the usefulness of, the result.

Why digitize this particular work? It is remarkable for its breadth and depth. The dictionary is a product of the St. Joseph’s Seminary in Macao. Established in 1728, this institution operated as a school for over 130 years, administered first by the Jesuits and later by the order of Lazarists, also known as the Priests of Congregation of the Mission. Gonçalves was born in 1799 and spent his entire career at St. Joseph’s after arriving in Macao in 1813. He died and was buried there in 1841. St. Joseph’s served two main types of students: Chinese students who were studying humanities and religion to pursue a career in the Portuguese civil service stationed in Asia or to continue their religious education and be trained for the priesthood/missionary field; and European students who needed to learn spoken Chinese to be better missionaries.

Father Gonçalves was an industrious scholar, with a passion for Chinese grammar, particularly of the spoken language. He worked with Chinese native speakers and drew on the work of European Sinologists who were actively studying and describing Chinese language and culture for European audiences, especially Robert Morrison. His teaching methods anticipated the insights of modern second language acquisition theorists (Levi 2007: 211-12). He emphasized active production in the target language. He was alive to the cultural embeddedness of language and the necessity of idiomatic understanding of words and phrases, not just mechanical one-to-one translation. His dictionary is accordingly rich in idioms. And at 757 pp. with 36,496 discrete lemmas, it remains the fullest Latin-Chinese dictionary ever produced.

I oversaw the project with modest grant funding from the Roberts Fund for Classical Studies at Dickinson College, where I teach and direct the digital project Dickinson College Commentaries. The central problem in digitization was the mix of traditional Chinese characters and the Latin alphabet, a combination that, at the beginning of the project, no commercial digitization firm we could find was equipped to handle.

On previous, non-Chinese, projects, such as the Frieze-Dennison Vergil dictionary, I had employed the Indian firm NewGen to excellent effect. This time, we had to begin in-house with ABBYY FineReader, the output of which had to be laboriously segmented and corrected by hand.

I had two Dickinson students as summer assistants in 2016: Siyun Yan, a Chinese-born computer science major, and Seth Levin (Dickinson ’19), an American Latin student.

ABBYY frequently crashed Siyun’s laptop, but with some care and persistence she was able to start editing the numerous Chinese characters that ABBYY could not immediately recognize. If you choose one of the options for a specific character that ABBYY suggests, ABBYY remembers the choice and learns to recognize it next time it occurs, which is the key advantage of ABBYY.

When the correct alternative was not forthcoming, and in cases where she was uncertain, Siyun used the Kangxi Dictionary Online Edition. She then added these new character to ABBYY so it could recognize them the next time they occurred.

One problem Siyun encountered was that of potential mistakes in the source. We had no project members trained in Classical Chinese, so there was no way to verify whether the Gonçalves’ translations contained any errors. (A “suggest a translation” button on the user interface is meant to help compensate for this lack.)

Seth Levin took the edited output from Siyun and transferred it into an Excel spreadsheet, proofreading the Latin along the way and attempting to match the Latin lemmas with those of the set of Latin lemmas used by the Perseus Project, the Morpheus lemmas. This attempt to line up Gonçalves’ words with those of other online Latin dictionaries was a gesture at Linked Open Data (LOD). LOD is the important DH principle holding that, to be most useful, a data set should be capable of combination with other similar data sets. It should ideally be possible to compare Gonçalves’ definitions of Latin words with definitions for the same Latin words in other dictionaries.

Coordination of data sets of places and people is relatively straightforward. Persepolis is Persepolis, Julius Caesar is Julius Caesar. Not so with lexical items. Gonçalves sometimes included separate entries for what could be seen as a single “word,” such as the three versions of bidens (having two teeth, a hoe with two teeth, or an animal with two rows of teeth), each with its own dictionary form or display lemma: bidens -tis (adjective), bidens -tis (feminine noun), and bidens -tis (masculine noun). The Morpheus set of lemmas used by the Perseus Project has only one entry for bidens.

In other cases orthographic variation made it seem that a word in Gonçalves was not in the Morpheus set. Seth was not aware, for example, that dedititius is but an old-fashioned version of dediticius. Another serious problem was the large number of placeholder entries and cross-references, entries beginning with et (“and”) meaning that it uses the definition of the following lemma, and v. (standing for vide or “see”) meaning refer to the listed lemma. To take one example of many, Gonçalves chose to combine the noun dedignatio, the participle dedignatus, and the verb dedignor into one entry. These problems led to numerous gaps in our master spreadsheet of Morpheus lemmas.

Siyun left Dickinson after 2016, and I turned to Qizhen Xie, and Chinese-born classics student at the University of New Hampshire, and later Brown University, who did substantial correction of the large spreadsheet. When he was no longer available, a large number of Chinese and non-Chinese speaking volunteers generously stepped in to help with the project. This stellar cast of high school, undergraduate, and graduate students from the US, UK, and China, were crucial to bringing the project to a successful conclusion. Predictably, however, many hands led to pervasive inconsistencies in lemma alignments, the handling of “v.” and “et” words, and in the exact method of listing and punctuating Latin headwords, an area where Gonçalves is idiosyncratic.

These problems resulted from my directives to modernize display lemmas and to coordinate with the Morpheus lemma set. Looking back, I should have committed from the beginning to an exact transcription of what was in the book. I should have postponed all attempts at Linked Open Data and modernization until we had an accurate digital representation of the print book.

The final phase involved extensive work on data management, tagging, and cleaning done by Lara Frymark, and funded by the Roberts Fund for Classical Studies. Lara graduated from Dickinson in 2012 with a classics major and earned a master’s in computer science from Brandeis in 2018. She brought order into what had become chaos by creating a reference system. She identified every word by its absolute position in the dictionary. The code includes the first letter of the word, the three-digit page number, a dash, and its position on the page. For example, c081-04_caementum indicates that caementum is the fourth word on page 81. Henceforth, we could look at any entry in our database and know unmistakably what it was referring to in the source material. As can be seen in the finished product, the code would also provide a convenient way of organizing the data to use as a web address.

The final hurdle to publication was proof-reading. The best way would have been to have a team of knowledgeable people go word-by-word and verify that everything matched perfectly. Given unlimited time, budget, and access to a pool of trained scholars, that would be no problem. Under real-world constraints, we decided to crowd-source the proof-reading using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a website that allows one to post simple tasks and get potentially hundreds of workers to chip away at them.

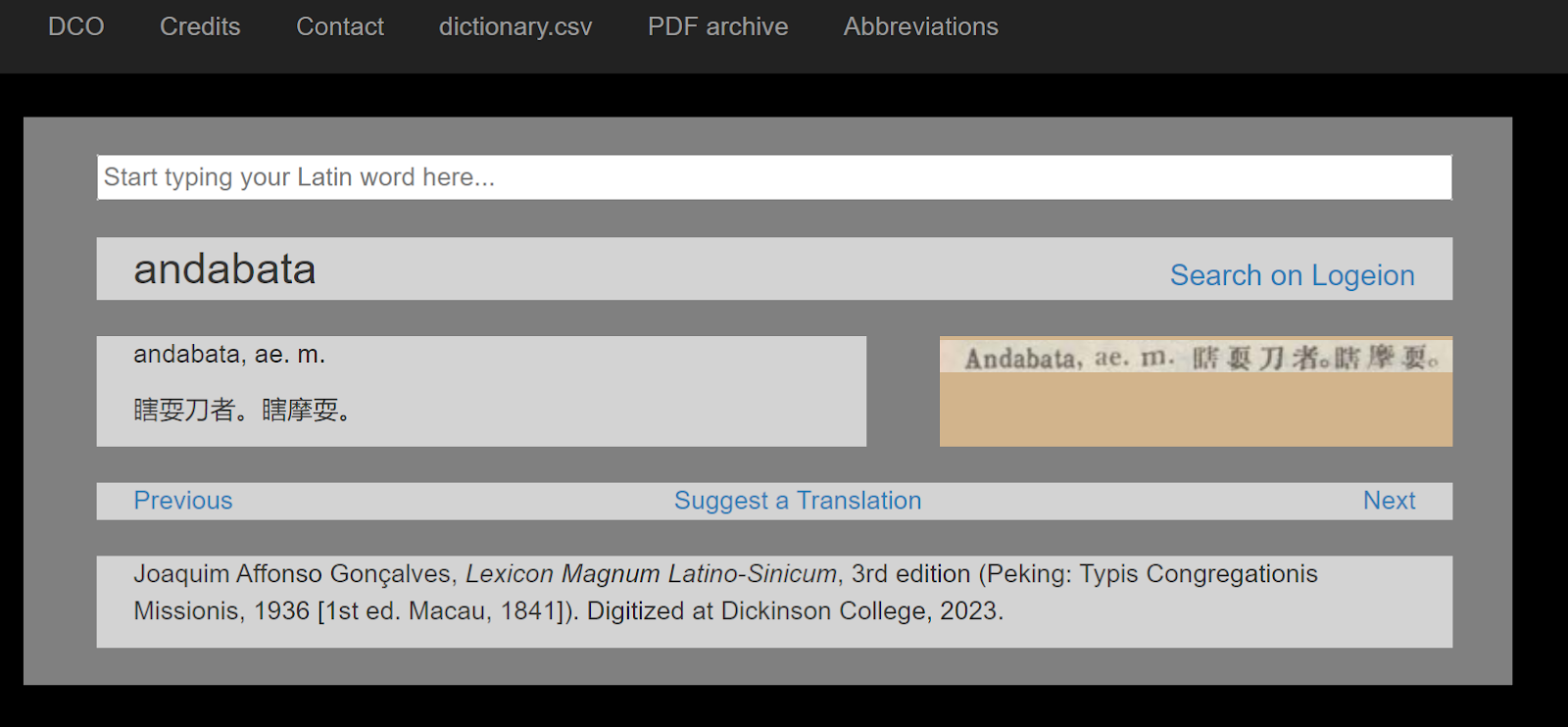

Lara placed an image of each lemma taken from the original PDFs next to our transcription and asked the user to indicate whether the transcription matched. Each transcription was tested four times, that is, four different people looked at the image and told us if we had transcribed it accurately. From this, we derived a confidence factor. If four people looked at a lemma and said the text matched, there probably weren’t any glaring errors. If zero people said the text matched, that one probably needed some work. This allowed us to cut down on the problem cases which we sent to Qizhen Xie, who generously helped us again in the final phases. We have no doubt that errors remain, especially in the later letters of the alphabet, which received less in the way of proof-reading from Chinese-speaking Latininsts. The user interface includes a way of easily suggesting corrections.

Lara also organized Gonçalves’ idiosyncratic formatting with a tagging system, so that if in the future we want to go in and change, say, all the third conjugation verbs to a more modern way of listing the principal parts, we can.

This is, to my knowledge, the most extensive morphological tagging of any Latin data set and would have many potential uses in Latin pedagogy.

The result is hosted in Heroku. This is because the Content Managment System we use for our classics-related digital projects, Drupal, is not equipped to host a database of this size. If I had been willing to approach the College about creating a new hosting solution, they might have agreed. Heroku isrelatively cheap, and administrsatively simple. It is not, however, a permanent solution. Soon the dictionary will be housed on the widely used Logeion, a splendid aggregator of Latin and Greek dictionaries based at the University of Chicago. This will will in effect create the Linked Open Data presentation that I always wanted but was unable to implement. The best plan for long-term survival of the data, in my view, is inclusion on Logeion and the free distribution now of the .csv.

Remaining problems:

- the current interface does not allow search by Chinese words

- proper names are not capitalized (in the source all words are capitalized)

- the data is not aligned with LiLa the newly emerging set of standard set of Latin lemmas

My questions for you, gentle readers of Digital Orientalist, are three:

- Is there a better way to digitize text with mixed Latin and Chinese scripts?

- How can others use or re-use this data to create useful resources?

- What similar works should be tackled next? Perhaps Angelo Zottoli’s (1826–1902) Cursus litteraturæ sinicæ? This synoptic guide to the Chinese tradition encompasses a vast range of texts from the Book of Songs to Qing-era examination essays, poetry, and letters, and includes facing Latin translation and notes.

References, Links, and Further Reading

Dickinson Classics Online. https://dco.dickinson.edu/ Resources for Chinese scholars of the Greek and Roman Classics

Dickinson College Commentaries. https://dcc.dickinson.edu/ Latin and Greek texts for reading, with explanatory notes, essays, vocabulary, and graphic, video, and audio elements.

Gonçalves, J.A. 1936. Lexicon magnum latino-sinicum ostendens etymologiam, prosodiam, et constructionem vocabulorum. Macai, in Collegio sancti Joseph. ab E. Rosa typis mandatum, 1841. (OCLC: 39488723). iv, 779 pages 32 cm. 3rd edition, Pekini: Typis Congregationis Missionis, 1892 (OCLC: 663670553). Repr. 1936 (OCLC: 42878372).

Levi, J.A. 2007. “Padre Joaquim Afonso Gonçalves (1781–1834) and the Arte China (1829): An Innovative Linguistic Approach to Teaching Chinese Grammar.” In Ridruejo Alonso et al., eds., Missionary Linguistics III: Morphology and Syntax: Selected Papers From the Third and Fourth International Conferences on Missionary Linguistics (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2007), pp. 211–231.

Uchinda, Keiichi. 2011. “The 19th-century Missionary Goncalves and Perceptions of the Chinese Language: The Portuguese Lazarist Church and its Linguistic Policy.” 東アジア文化交渉研究 第4 号: pp. 229-241.

One thought on “The Digitization of a Large Latin-Chinese Dictionary”