This is an interview by contributing writer, Emma Donington Kiey, with fashion designer Ana Cordoba Crespo, on her involvement with the project “Making Fish Skin Pattern-based Garments: Developing Digital Tools for the Fashion Industry Based on Ainu Fish Skin Robes and Japanese Kimono Patterns,” alongside project leader, Dr. Elisa Palomino.

This project physically and then digitally, recreated the Ainu amip (robe) traditionally made of fish skin, and combined this with the Japanese katazome dyeing technique. You can see more information on the extended project and Dr. Palomino’s work here. You can also visit Ana’s website here to see her impressive portfolio of 3D printed fashion designs and more.

Q1: Emma Donington Kiey: In the description of your background in the Responsible Fashion Series report for this project, you wrote that your “ultimate goal is to make fashion more inclusive, where coding reinforced thread.” What did you mean by this?

Ana Cordoba Crespo: What I meant by the “coding reinforced the thread,” is that I think fashion is still a very craftsmanship-focused industry. Even though technology has already integrated into and developed in a lot of industries, I think fashion is still not really wanting to include technology as much, at the moment it is still considered something cold and even scary to some. So what I want to encourage for the future, is that a designer is not only going to be behind a sewing machine, but are also going to be creating through coding, and we’re going to see the implementation of innovative technology in the design process. Especially with code and other technological advancements, there’s often a stereotype that it’s predominantly for those with a technical approach, while fashion is perceived as being more suited for the creatively inclined. However, I believe that you can successfully integrate both worlds.

The other part of that quote, the idea that fashion can be more inclusive, is that historically, the fashion world has been criticised for its lack of diversity in terms of body types, races, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Making fashion more inclusive means breaking down barriers and ensuring that people from all walks of life feel represented and catered to in the fashion industry. For example, the programmes I use allows you to customise the garment or avatar to fit and represent different bodies. By leveraging coding and digital design, you can potentially make fashion more accessible whether through customisations, virtual try-ons, or other technological advancements that cater to diverse body types, styles, and preferences. By embracing coding as a fundamental aspect of fashion design, the designers of the future can push the boundaries of creativity, accessibility, and sustainability in the industry. They become not just artisans of fabric, but innovators at the intersection of fashion and technology, shaping a more inclusive and forward-thinking landscape for the fashion world. That’s why, in the case of the Ainu robes, utilising technology was inspiring in that you are then able to experience it in a virtual reality that is quite different to a standard photograph, it provides more specific details, different points of view, and you’re able to get as close as you can get to the material without having it physically in front of you. That kind of experience is only possible through the hands of technology.

Q2: The project on Ainu robes started when you were a student at Central Saint Martins in Fashion Print. How did you come to be involved in this project? Could you give some background on how the project was started, and what its aims were?

In my second year, Dr. Elisa Palomino was my academic tutor, and I remember that I asked Eisa I was really keen to use 3D-rendering software like CLO3D even though it wasn’t part of the curriculum, so I started developing my skills through YouTube, and implemented it in independent projects. By the end of the year I had created “virtual twins” of all my garments through CLO3D. Elisa knew I was using it, and asked me if I would be interested on working with her on a personal project. She explained all the research she had done on fish skin materials, and introduced me to the Ainu robes and culture. The virtual recreation of this robe was my first contact with Ainu and Japanese culture. My role on the project was to take the physical Ainu fish skin robe Elisa had made during her time in Japan, and make a 3D animation where you could adjust your perspective and see the robe from different points of view.

It was a really important aim for the project that the final product included an animation and not a static image because Elisa wanted it to be brought to life, to look as similar as possible to if you were actually there looking at it. I used both CLO3D and Blender; the first to create the pattern, sewing and physical properties of the robe itself. Meanwhile, Blender served as the canvas for animating the scene, where I modelled elements such as a boat, the ocean, and the Ainu avatar. Something as well to highlight, I think, is that this project was a great opportunity for me to learn more about the digital design process through trial and error. It was very collaborative, and we worked together to fix little mistakes and make changes. For me, it was an amazing learning experience because while working with Elisa I learned so much not only about the culture of the Ainu people, but also developed my own technical skills.

Q3: Do you know how the initial idea for a project on Ainu fish skin robes was first conceptualised?

Elisa had spent a few months in Hokkaido, Japan, and she learnt about the Ainu culture, and worked a lot with the Ainu community in Biratori learning traditional crafts. For example, dyeing fabrics, drying and preparing the fish skin in the process of pattern making, and then constructing the robe. While I did not have the same depth of knowledge compared to what Elisa gained from this experience, it was inspiring to see what she had accomplished and the craftsmanship and cultural heritage of Ainu fish skin robes, and the opportunity to celebrate and reinterpret these traditions through modern digital techniques. I also appreciated the opportunity to learn about Ainu clothing and its production, and how knowledge of their methods can contribute to sustainability and zero-waste in the fashion industry – this was also a central aim of the project. What particularly fascinated me was that the entire process relied exclusively on materials found within their surroundings. In our current culture, a lot of the materials we use only serve to pollute the planet. Using fish skin from salmon they are eating and using is really impressive because they are actually using what would typically considered a waste product.

Q4: How did you balance the digital technologies and modern approaches you were using, whilst respecting the integrity of indigenous materials, knowledge and their historical legacy? How important was the context of these robes in a digital space?

There was a lot of insistence and effort put into maintaining the context of these garments. At the beginning when I first started rendering the robe in CLO3D I used a default male avatar, but after talking with Elisa, she wanted to represent the physical features of modern Ainu people in an authentic way. I used Blender to change the body type to make the avatar a bit shorter and add longer hair and a beard, similar to the images Elisa shared with me of the people she worked with in Hokkaido. Elisa didn’t want the 3D animation to overshadow the Ainu culture it originated from, she wanted it to be something that could amplify its understanding around the world.

Q5: Could you maybe explain how CLO3D is different from other 3D rendering software, and why it was so useful to this project?

The main difference with CLO3D is that it is the one of the only primary softwares for digital garment design and simulation. You can basically do everything you can do to a physical fabric on the programme – you can virtually sew, pin, cut and assemble a piece of clothing as if you were doing it physically. CLO3D allowed me to explore the design elements, fit, and movement in a virtual environment. It’s a very realistic method of doing trial and error. Unlike other general-purpose 3D-rendering technologies, CLO3D offers specific features tailored to the fashion industry, such as pattern creation, fabric simulation, and virtual fitting.

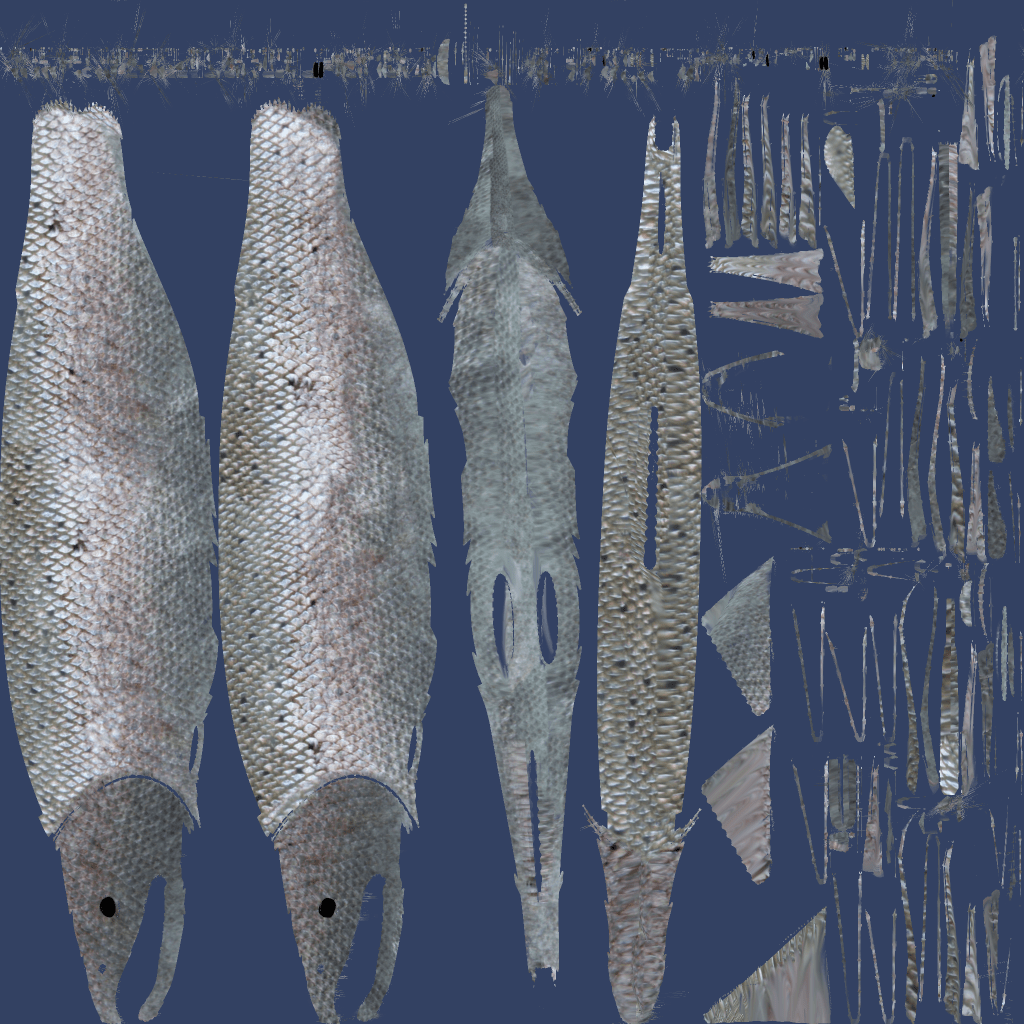

In this project, components such as the boat, the avatar, and the ocean were all modeled using Blender. However, for creating garments, CLO3D proved to be the most effective tool. Another really important thing that the software was suited to, was that we wanted to show the construction of the fish skin as realistically as possible. Obviously, fish skin is not like other fabrics where you can buy whatever width you want, but you are more limited to the size of the fish. So, you needed to kind of connect pieces together, and in the end, you wouldn’t have a pattern as clean as maybe a man made fabric. For this project, I first developed the pattern in Photoshop by making the fish skin flat, and then duplicated it as needed, allowing for some asymmetry. CLO3D also has a feature where it will automatically tell you the most efficient way to organise the fabric for the pattern, attempting to avoid any waste of the fabric..

Q6: What conclusions did the project come to on the combined perspectives of traditional and innovative technologies for designing, constructing, and manufacturing modern garments, and what direction could this research take in the future?

Many aspects of the project are still ongoing, and there are many research projects into the use of fish skin as a fashion material. But for me, at the time I finished the 3D animation, the conclusions I made personally were that while digital tools offer unique possibilities, they cannot fully replace the artistry and cultural significance embedded in traditional techniques. By integrating both perspectives, we can create garments that marry cutting-edge design with timeless craftsmanship, appealing to modern sensibilities while respecting heritage and authenticity. I believe that creating digital twins of physical garments opens up the potential to reach a wider audience, as these garments can now be experienced not only in the physical realm but also in the virtual world. Through virtual reality and other emerging technologies, craftsmanship techniques from around the globe become accessible to a broader audience, transcending geographical limitations and fostering greater appreciation for traditional artistry worldwide.

I think that, nowadays, because the fashion world is not the most sustainable industry right now, that this project shows how innovation can actually drive sustainability. The combination of innovation and tradition also showcases past techniques that allow for cultural storytelling which I think is really beautiful. I think that something important to continue to do, and something Elisa emphasised in the animation, is that when you make a garment through craftsmanship, there are always mistakes. Technology may cause a tendency of making things perfect, but we wanted to show the imperfections and human error. Bridging this in an immersive virtual reality could not only enhance the storytelling aspect of the garments but also provide users with a unique and engaging way to experience fashion.

If you would like to read even more about this fascinating project, a book edited by Annick Schramme and Nathalie Verboven entitled Technology, Sustainability and the Fashion Industry will be published 15th May, 2024. Chapter 6 (Digital Tools in the Fashion Industry: fish skin garments and Ainu fish skin traditions) will cover Ana and Dr. Elisa Palomino’s work.

One thought on “Ainu Fish Skin Robes and 3D Digital Animation for Sustainable Fashion Production: An Interview with Ana Cordoba Crespo”