I want to start with some general questions that many Digital Orientalist contributors will have asked themselves privately or in posts on this website: How can the better part of colleagues be introduced to DH technology or software without forcing a 6-month Python course or SQL basics on them? When does technology start to hinder philological workflows instead of enhancing them? How much basic research do low-resource languages need in order to be able to use generic tools in the ever-growing and increasingly complex sea of digital humanities and thus also present significant and innovative research results?As part of the workshop “Making the Most of Digital Humanities for Tibetan studies: An Introduction and Practical Guide”, which I co-organised with Digital Orientalist editor Rachael Griffiths at Wolfson College, University of Oxford, in December 2023, we aimed to provide answers to some of these questions specifically for Tibetan studies. A big thank you is due to our gracious host Dr Lama Jabb, Head of Wolfson College’s Tibetan & Himalayan Studies Centre.

Preliminary considerations

We had advertised the aims of the workshop quite ambitiously as “managing your research data, learning the basics of social networks and text analysis, and doing your own OCR with Tesseract and Transkribus”. As Rachael and I have been passionate about the digital humanities for a number of years, we wanted to take the opportunity to share what we had learnt on this journey with our peers. We had sent out a simple questionnaire in advance to clarify the technical interests, skills, wishes and expectations of the participants. As expected, there were few specific suggestions, but rather a desire for inspiration, learning and a general broadening of horizons. However, we did have some requests for the basics of corpus analysis and concordance, an introduction to Tibetan OCR, and how to efficiently and comprehensively query databases and search available catalogues.

I was immediately reminded of Roberta L. Dougherty’s talk at the recent Digital Orientalist conference “Sustainability in the DH”, who spoke about “Object Lessons in Sustainability of Complex Digital Projects”. In the course of her presentation, she glossed over the 1989 Kevin Costner classic Field of Dreams as follows: “If you build it, will they come?” Roberta pointedly addressed the fact that the existence of databases, tools, or web applications alone is no guarantee that they will be found and used. It was therefore important for us to present a selection of practical platforms, beginning with the popular The Buddhist Digital Archives (BUDA) and emphasising the very useful cooperation of this project with the Internet Archive. For concordances and simple corpus analysis, I chose AntConc because I also use it for my own historical research. Despite the very intuitive workflow and the excellent documentation, there is one major disadvantage of AntConc, namely that Tibetan Unicode is not yet supported (for reasons that escape me). Therefore, I have also introduced the web app Translit CrossAsia from the CrossAsia platform, which enables fast transliteration. CrossAsia and especially the CrossAsia LAB are, in my experience, almost completely unknown outside of Germany, and I will hopefully be able to go into more detail about the features of this portal in a future DO post.

Rachael and I decided to split the OCR/HTR component according to our areas of expertise, so Rachael would introduce the fine art of Handwritten Text Recognition via Transkribus (see her previous posts on the subject here and here) and I would present the Tesseract-based OCRmyPDF which is operated through a command-line interface (CLI). We also arranged the afternoon session of the workshop the same way, with an introduction to Obsidian for managing research data and notes (Daniel) and a first look at the possibilities of social network analysis with Gephi (Rachael).

Theory to Practice: Workshop reflections

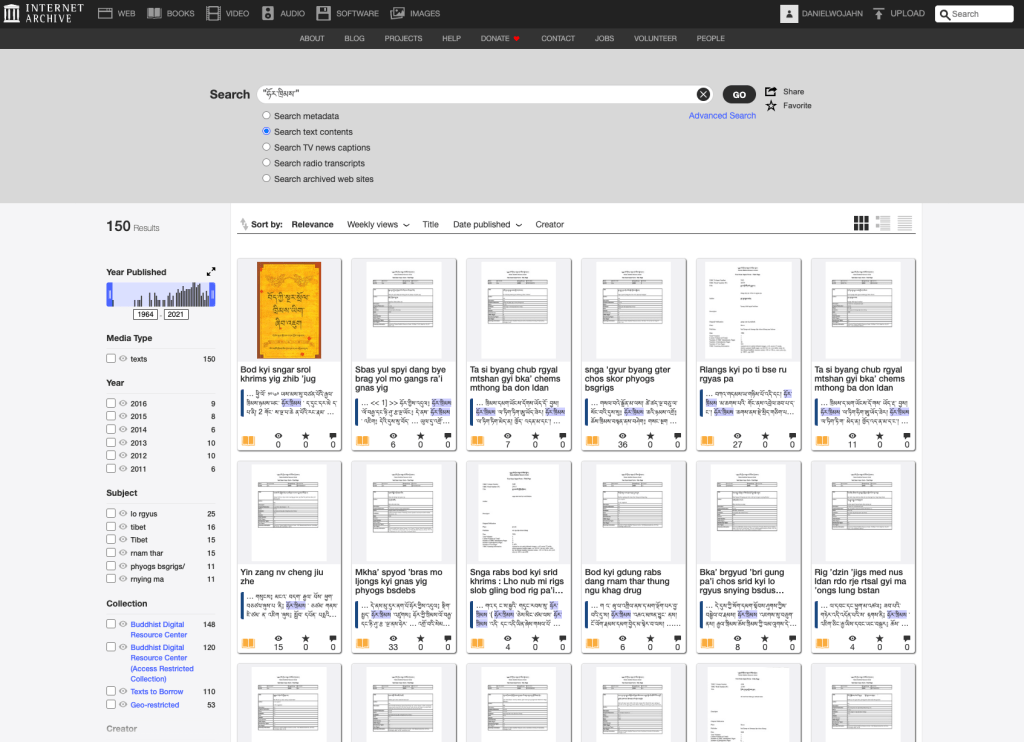

Our practical walkthrough of the Buddhist Digital Archives was a great exercise for everyone to ease into the workshop. Any student who has been involved in Tibetan or Buddhist studies for some time will already have come into contact with this invaluable resource, so all participants were familiar with the user interface and basic functions. However, as BUDA was completely revamped about two years ago, both in terms of web design and the underlying database structure, many colleagues still struggle to find “even half of what used to be on the old website” or have problems with its navigation. Some participants seemed to have had similar experiences, but we are pleased to report that these problems should now be a thing of the past. While the ever-growing number of e-texts being added to BUDA lend themselves to fine-grained searches, most of them are not easily accessible or retrievable due to numerous copyright restrictions. To the great surprise of all participants, however, they are searchable via the ‘Text Content Search’ of the Internet Archive and linked to the respective page (which is unfortunately not always the case with the e-texts in BUDA itself). Note: When searching for compounds, always put your query in inverted commas!

My subsequent presentation of AntConc was unfortunately not sufficiently structured and sometimes created more confusion than clarity. The creation of an individual corpus and the subsequent collocation would have benefited from a gentler introduction to the general corpus linguistic methodology. The KWIC feature, i.e. keywords in context, on the other hand, appealed to many and you could see participants recognising the potential value for their own research and asked more questions.

We started our afternoon session with the Personal Knowledge Management System (PKMS) Obsidian (see here also Cornelis van Lit’s article “How to level up in DH”). Firstly, I was keen to explain the concept of “future proofing” with the “files before apps” approach through practical examples, because every Obsidian note is ultimately just plain text markdown in local folders. Even if Obsidian would break and could no longer be opened, you could navigate the notes in a universally readable format in any file manager and use them with any text editor, including the default ones that come with Windows, macOS and most Linux distributions. I also featured a selection of my favourite plugins such as Admonition, Omnisearch or Iconize and the super useful in-built Graph View. I then went through my own PhD Obsidian project and the folder structure I use (kudos to my mate Michael Ium who once suggested a similar way of working in Scrivener). After just a few minutes, the participants recognised the incredible potential of a PKMS and appreciated the user-friendliness of the internal links and the PDF embedding as well as my proposed method of organisation by source, person, and terminology.

Scheduling the OCR/HTR session in the afternoon was probably not the best idea. As the morning sessions already covered more new than familiar terrain and the technical level of the participants was so different, we decided after brief consideration to only present Transkribus due to its convenient GUI and to postpone any CLI operations, as the preparations for this would probably have taken longer than the planned 45 minutes. Nevertheless, Rachael did her best to ensure that everyone present had enough knowledge to continue experimenting themselves.

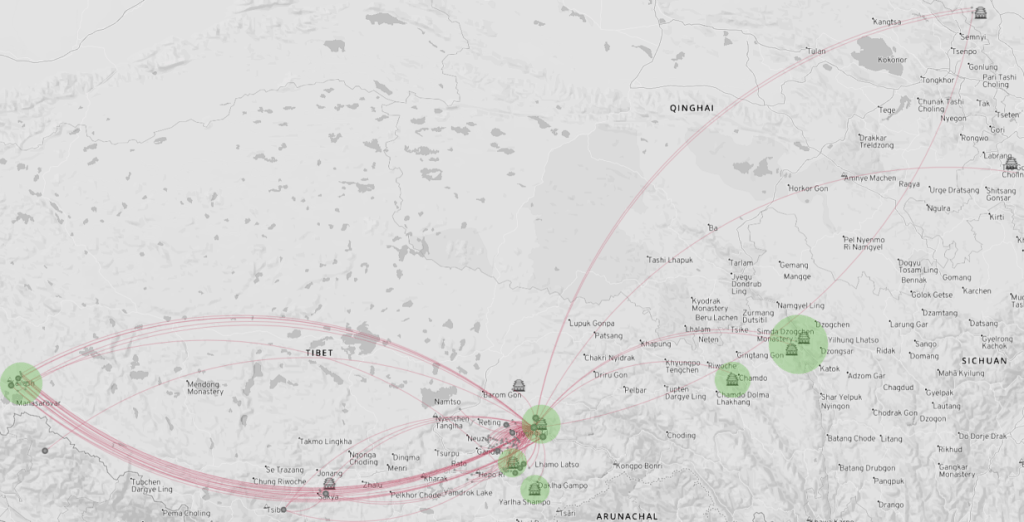

To round off our introduction into the world of digital humanities for Tibetan studies, we both presented one of our social networks we created with Gephi, an open-source software designed for network analysis and visualisation. Our raw data comes from a collection of letters by Chennga Drakpa Jungné (1175–1255), which I am working on for my doctoral thesis, and from Rachael’s doctoral research on Sumpa Khenpo Yeshe Peljor (1704–1788). Since network analysis is about turning complex relationships into visual maps (or, as Matthew Hayes so aptly put it, “Seeing the Forest from the Trees”), we outlined several use cases tailored for application in Tibetan studies. Using Rachael’s data, we were able to show how historical connections can be mapped and the movement of historical figures, texts or artefacts can be traced to understand cultural exchange and influence. I then used my dataset to illustrate the structure of monastic lineages, teacher-student relationships and patronage networks and the extent to which they enable an analysis of social, political and cultural dynamics within historical Tibetan societies.

Finally, we also discussed the possibility of visualising textual relationships, i.e. examining connections between different Buddhist texts or philosophical concepts and understanding how ideas evolve over time, how commentaries relate to the original texts and, more generally, how to approach networks of influence within Tibetan literature. The visual conclusion of our workshop was well placed. Our participants were particularly enthusiastic about the possibility of using this method to visually support the often difficult-to-follow chronological paragraphs and historical retellings that eventually find their way into Tibetological research outputs.

Conclusion

In my opinion, our first workshop experiment was a successful attempt to bridge the gap between technological advancements and the core skills of philology. While the allure of complex software and advanced tools is undeniable, sometimes simpler solutions can be equally effective. Resources such as BUDA and Transkribus, combined with readily available but under-explored options such as Obsidian, can significantly improve research and data management workflows. The journey often begins with a single step, and even “low-tech” tools can empower us to achieve high rewards in our research. Reflecting on the workshop, I am particularly inspired by the insights that emerged from navigating the diverse levels of digital humanities knowledge among participants. It was a rewarding experience and I am optimistic that we can repeat this workshop in 2024!

I sincerely hope that our first workshop served as a springboard and encouraged participants to explore the enormous potential of digital humanities in their own work, to continue learning and experimenting to unlock new avenues of inquiry within the field of Tibetan studies.

One thought on “Low Tech, High Reward? A Report on the Workshop “Making the Most of Digital Humanities for Tibetan Studies””