TEI (text-encoding initiative) is a digital humanities method that enriches plain text transcriptions using .xml tags. It is most commonly used in cultural heritage projects, and in many ways has become the go-to method for structuring digital transcriptions of historical manuscripts and correspondence. There are many different texts and written materials that TEI can be useful for, and as I’ve come to learn the tools of TEI are very versatile. The TEI organisation and its guidelines have continued to expand and adapt to the needs of researchers, regardless of language, since it was established in 1987 (see figure 1).

This article is part one of two, introducing the collection that inspired this project proposal: the diaries of zoologist and Japanologist, Edward Sylvester Morse detailing his travels and observations in Japan, the full collection of which is housed at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, USA. In this article, I will also outline the ways TEI would be particularly helpful in various paths of research into Morse’s diaries, and I will discuss the early TEI building blocks of this project.

The Digital Orientalist has published several articles over the years on different TEI projects: “Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) for Ottoman Studies” by Fatma Aladag, “Legacy cataloguing and TEI: David Pingree and Wellcome Collection,” by Alexandra Eveleigh, Stephanie Cornwell, and Adrian Plau, and several articles on TEI spanning general digital humanities and South Asian manuscripts by Adrian Plau independently. Therefore, this article will not explain all the fundamentals of TEI, but instead the features that are particularly useful to researching Morse’s diaries. I have also included a short glossary at the end to explain some common terminology.

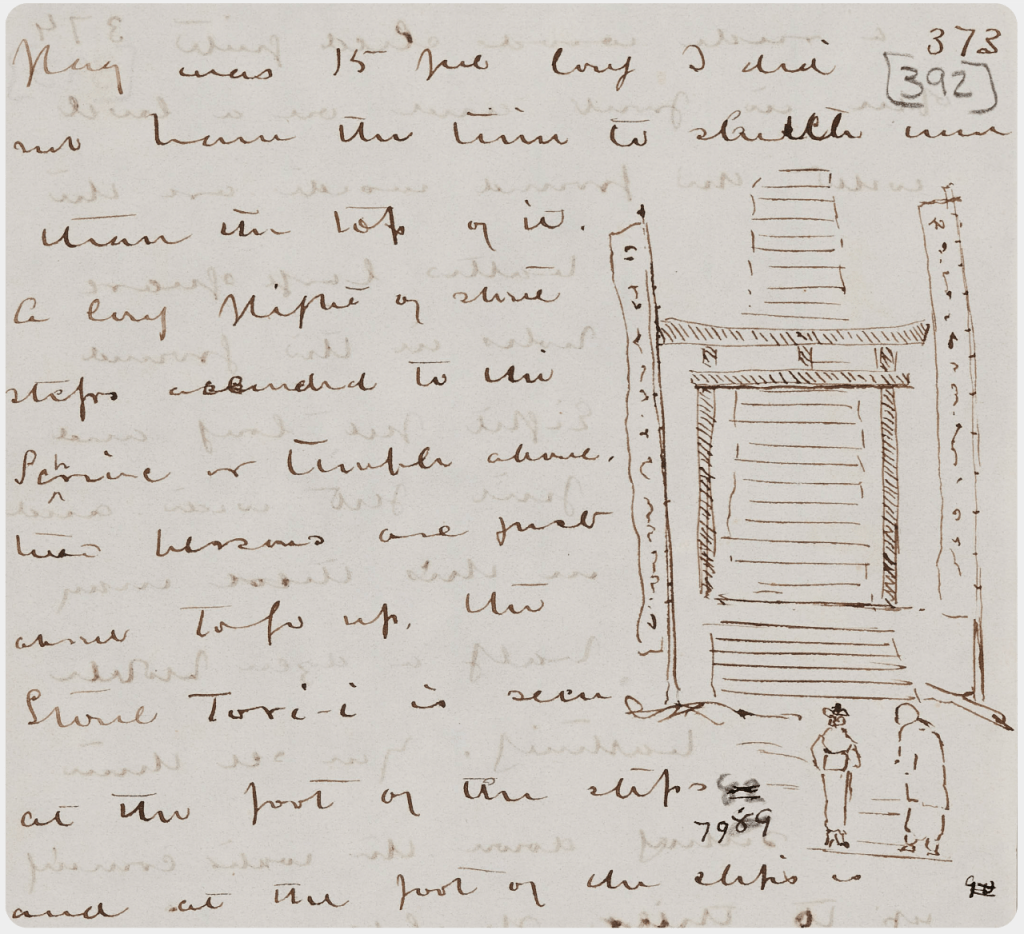

I first learned about Edward Sylvester Morse and his diaries through the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture (SISJAC) in Norwich, UK, as they had been the ones to begin digitising the diary pages on a short trip to Massachusetts in early 2023. Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925) was a zoologist who lived in Salem, Massachusetts, before travelling around Japan from 1877 intending to only continue his work on coastal brachiopods. However, Morse inadvertently made more significant impact during his travels. He was offered a three-year zoology professorship at the University of Tokyo, and while travelling discovered the Ōmori shell mound which is considered by historians as a turning point in the archaeology of prehistoric Japan. Morse diligently kept a diary of his time in Japan, often day-by-day, writing about his observations on Japanese life, accompanied by small illustrations (see figure 2).

In addition, from 2022, SISJAC undertook a series of pilot projects using digital methods called ‘Digital Futures’ funded by the Ishibashi Foundation, which involved a project based in Salem that you can read about here, led by Dr Nicole Rousmaniere. As such, members of SISJAC are very familiar with Edward Sylvester Morse and similar Orientalists also living in Salem around the time of its Victorian ‘Japan Craze.’ After learning about the digital collections at the PEM, and the move to put the transcripts online, I began thinking about how TEI could be helpful in further facilitating research into a fascinating and perhaps surprising history of Salem and of US-Japan relations.

You can find transcriptions for all 3,000 pages of Morse’s diaries whilst in Japan, all thoughtfully transcribed by Hina Hirayama, online through the Phillips Library Digital Collections, among other related materials. Morse also collected ceramics, postcards, photographs and personal correspondence. There are currently only plain text PDF files of the diary transcriptions (see figure 3) as only a small percentage of the original papers have been digitised and are not yet published on the PEM’s website. The PEM’s collection of Japanese objects is extensive, and the metadata of Morse’s diaries identifies relevant topics and people either relating to Morse or cross-overs in key themes (see figure 4).

Recently, I travelled to Oxford to study at the University of Oxford’s Digital Humanities Summer School on their TEI course to refresh my knowledge, and apply what I learned to the Morse diaries mark-up. The course lecturers from the University of Cambridge Digital Library discussed their projects including FIHRIST: Union catalogue for Islamic and other Middle Eastern Manuscripts led by Yasmin Faghihi, Alasdair Watson and Huw Jones. We were also introduced to projects by guest lecturers Sebastian Dows-Miller and his work on scribal abbreviations in French manuscripts, Elizabeth Smith from the Darwin Correspondence project, and Chistopher Ohge on using TEI to analyse the work of Herman Melville.

A fundamental aspect of the course I most enjoyed was the practical workshops relevant to our own projects. For instance, we learnt how to edit TEI schemas to be used in Oxygen (the most common software for transcribing with .xml tags), how to build TEI headers, how to use XPath to navigate our documents, and how to transform .xml into .html. We also were taught how to create more complex strings of tags, and incorporate more detail to element tags through attributes. These attributes are designed to provide further machine-readable clarification on the tagged word’s semantic field, formatting etc.. For instance, tagging the underlined word “Hayaku” from the text shown in figure 3 could be tagged with the following:

<foreign rend=”underline” xml:lang=”ja”>Hayaku</foreign>

There are many advantages to working with TEI for someone not adept with coding; one most notably being that depending on the nature of your research, and the questions you are asking, the tags you use can be as simple or as complicated as you need. In the case of Morse’s Japan Diaries, I was initially drawn to them because I was interested in his observations of Japan, the language he used to describe his experiences and what he learnt about Japan and Japanese culture in the early years of the Meiji period (1868-1912). Using TEI would be an effective method for researchers to organise the text into semantic and descriptive tags. For example, using tags you could explore linguistic trends, find patterns in the observations Morse makes, or annotate other technical terminology relating to his research. Furthermore, using tags to describe the text aids in quicker and more informed searchability of the collection.

Fundamental to any digital humanities project is its accessibility, and being UK-based, my research into Morse’s papers which are based in Salem, Massachussets, US, also aims to facilitate global research by other scholars. TEI also helps future-proof and digitally preserve historical texts, and so while it is exciting to have the opportunity to develop my TEI mark-up skills, it is an important tool for the general future of museum collections and research.

Glossary

– Element: An essential part of .xml markup in TEI. Elements are represented by tags (e.g. <p> <text>) that define the structure and content of the selected text.

– Attribute: Additional information added to element tags that provide more details (e.g. <date rend=”underlined”>1st June 1878</date> and must be linked to an element.

– Tag: The markup used to denote elements. Tags must be paired with an opening tag at the beginning of the selected text (e.g., <p>) and a closing tag (e.g., </p>). An exception to this rule of pairs is a self-closing tag indicated by a forward slash, which means you only need one tag. This makes commonly used tags such as a line break <lb/> less visually overwhelming in the document.

– Header: This is the introductory section of a TEI document where you will find metadata such as the title, author, and collection number, usually indicated by a <TEIHeader> tag.

Additional Reading

Burnard, Lou. What is the Text Encoding Initiative? How to Add Intelligent Markup to Digital Resources. (Marseille: OpenEdition Press, 2014.)

Sharf, Frederick ed. “A Pleasing Novelty” Bunkio Matsuki and the Japan Craze in Victorian Salem. (Peabody Essex Museum: Massachusets, 1993).

The Peabody Essex Museum also provide an excellent list of resources for further reading on Edward Sylvester Morse: https://pem.quartexcollections.com/collections/edward-s.-morse/additional-content

very interesting read 🐚