Tokenization, the process of transforming human text into machine-understandable units of meaning (tokens), is a foundational step in language modeling. It is also one of the most underappreciated ones, with high-level tasks like reasoning, translation, or classification stealing public attention. Beneath these advanced capabilities lie tokens, the building blocks of text which for human readability are rendered as letters, characters, words, or phrases, but which function as numbers inside a language model.

General-purpose LLMs such as ChatGPT or DeepSeek are designed to answer questions in many languages. Each such model has an associated tokenizer which parses and translates user queries into numerical sequences. These numerical sequences are then passed on to the model for further processing. However, since human languages differ from each other in how they encode the world, a tokenization method that works well for space-divided and alphabetic languages such as English or Polish might work suboptimally for Chinese or Japanese. In this post, I want to draw attention to some of the problems of general-purpose tokenizers and how they might affect domain-specific research questions pertaining to Chinese data.

In English, we can easily split any text into words by spaces (“pre-tokenization”), and then divide each word into individual letters: “hello world” becomes “hello” “world,” and “hello” becomes “h” “e” “l “l” “o.” Each unique letter is then assigned a different ID. For example, “hello” can be represented as [104 101 108 108 111], where each decimal number corresponds to a different character in the ASCII table. ASCII allows us to encode 128 different characters, including non-printable ones such as the new line symbol (\n) and printable ones such as digits (0-9), Latin alphabet, and punctuation marks. This allows us to encode the majority of English texts using a very small vocabulary.

What would happen, however, if we wanted to use the same method to tokenize a Chinese text? We would need to expand the vocabulary to cover the common Chinese characters and then represent each character in the input sequence as a unique number. For example, the popular tokenizer bert-base-chinese, which has a vocabulary of 21,128 symbols, encodes 蛇年大吉 as [6026, 2399, 1920, 1395].

Notice the huge difference between the two examples: we needed as many as five tokens to encode a simple word “hello” in English. Only four tokens were needed to encode something as complex as the Lunar New Year greeting in Chinese. This difference occurs because the length of the tokenized sequence is inversely correlated with the size of the vocabulary. In the English example, the vocabulary is small, but the sequence long; the opposite is true for Chinese.

Finding the right balance between vocabulary size and sequence length becomes particularly important in text generation (as in RAG applications), given that the generation of each token requires a new pass through the entire model. This is computationally expensive. Moreover, smaller vocabularies limit the context size, since we need a lot of tokens to encode little information. To address such inefficiencies, various tokenization methods have been developed, including Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), WordPiece, and Unigram, which compress input sequences and reduce the amount of required computation. Being devised mainly for English data, however, these compression methods introduce a number of unacknowledged issues into Chinese tokenization.

The training of a BPE tokenizer usually starts with a basic vocabulary (e.g., individual letters) and a pre-tokenized training data split by spaces, punctuation, and other symbols defined in the pre-tokenizer’s regex. The algorithm then iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of symbols into new, combined tokens. For example, the word “hello” might become “he” “l” “lo,” as both “he” and “lo” are common pairs of symbols found in various words (her, hefty, hen, or low, lorry, long, etc.). This reduces “hello” to three tokens. If “he” and “l” appear frequently together, they can be merged into “hel.” And if it turns out that “hel” and “lo” also appear frequently together, “hello” might be assigned its own unique token. At the cost of increasing the vocabulary size, we can thus reduce the length of the sequence. [1]

A common optimization of BPE, counterintuitively named “byte-level BPE,” starts with a basic vocabulary of 256 bytes instead of individual symbols. This ensures a fixed-size initial vocabulary and guarantees that every character in the Unicode table can be represented. The tokenizer first transforms each symbol into a UTF-8 representation, which might produce from one to four bytes per symbol. For example, the Chinese wish 蛇年大吉 is represented as [232 155 135 229 185 180 229 164 167 229 144 137], with three bytes for each character. BPE then merges frequently occurring byte pairs.

The number of merges is fixed at the beginning of training as a hyperparameter; GPT-2 has a vocabulary size of 50,257, which corresponds to the 256 base tokens, a special end-of-text token, and the symbols learned with 50,000 merges.

WordPiece is similar to BPE, but instead of merging the most frequent pairs, it merges pairs based on their likelihood of occurring together relative to their individual frequencies (mutual information) in the training data. For example, if “h” and “e” appeared together very frequently but rarely independently, it would be beneficial to merge them into “he.” Conversely, if they appeared together only a few times but were frequent individually, creating a specific “he” token would not be worthwhile.

Although such merging solutions work well for alphabetic, space-delimited languages, many problems emerge when they are applied to Chinese.

To begin with, both BPE and WordPiece implicitly assume a specific definition of a “word,” as reflected in the pre-tokenization step which splits the training data on whitespace and thus prevents cross-word merges. In Chinese, however, the very question as to what counts as a “word” remains problematic. With no spaces, there is nothing that prevents two characters from being merged into a new token, even though they might not belong to the same word.

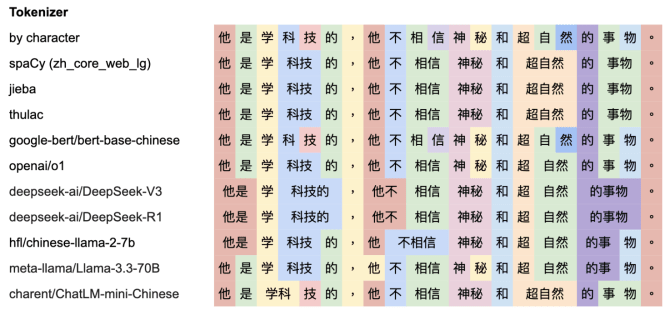

The above point is important given that the BPE tokenizer handles a given input sequence by merging basic elements in the order of learned merges. Consider Dung Kai-cheung’s sentence 他是学科技的,他不相信神秘和超自然的事物 (“He studied electronics and didn’t believe in esoteric or supernatural things”), which I analyzed in my previous post. I have tokenized this sentence using several open-source tokenizers from HuggingFace as well as models trained specifically for Chinese NLP tasks (spaCy, jieba, and THULAC). In the following table, characters marked with the same color were merged into one token.

While traditional segmentation tools perform well, correctly capturing polysyllabic (multi-character) expressions, LLMs struggle to parse this sentence correctly. The LLaMa-family models incorrectly merge the non-existent word 的事 instead of the correct 事物. This happens because 的 and 事 were merged earlier than 事 and 物 during the tokenizer’s training. The DeepSeek models wrongly merge 他不 and 的事物 into single tokens. Another model, charent/ChatLM-mini-Chinese, incorrectly merges 学 and 科 into one word. While 学科 is an otherwise valid word meaning “academic discipline,” it should not be merged in this context. Again, this error arises because 学科 appeared more frequently than 科技 (technology) in the training corpus, causing the 学—科 merge to be learned earlier.

Another hidden problem caused by the merging algorithms is the resulting Chinese vocabulary. For example, while BERT nominally uses WordPiece, which distinguishes between beginning tokens and non-beginning tokens (e.g., “he” in “hello” and “##he” in “coherent”), it has hard-coded instructions to segment Chinese text into individual characters. Consequently, there are no true “word pieces” to speak of. This results in a curious situation where the bert-base-chinese tokenizer has an unusued “subword” version for each of the 7322 CJK characters. For instance, 我 has two versions: a beginning 我 (encoded as [2769]) and a non-beginning ##我 (encoded as [15862]). The latter is useful only if the input text is already pre-tokenized into words separated by spaces and if the tokenize_chinese_chars flag is set to False. As a result, the model’s vocabulary is needlessly bloated with thousands of rarely used non-beginning tokens, likely diminishing the model’s performance.

Yet another vocabulary-related problem is dataset contamination. Since the list of merges is publicly available for open-source tokenizers, we can indirectly learn about the kind of data these tokenizers have been trained on. It has been recently shown, for example, that in GPT-4o many of the longest Chinese merges contain terms specifically used in the contexts of gambling or pornography. In other words, every time GPT-4o generates a token to answer your question, a tiny bit of probability is assigned to such explicit content.

All the above issues place researchers in a predicament where sophisticated models with billions of parameters are trained on incorrectly tokenized data. While this might not impact common chatbot applications, it can hinder domain-specific research. For example, sentiment analysis might be sensitive to the token layout in the input sequence; is 他不 喜欢 (“he doesn’t” “like”) the same as 他 不喜欢 (“he” “doesn’t like”)? Scholars might also want to use generative models for classification tasks, a research method encouraged by the “structured outputs” feature which ensures that an LLM generates responses that adhere to a supplied JSON schema. But if the names of different classes are unevenly tokenized (some requiring two tokens, some three, some left in their byte-level BPE representation, etc.), the general-purpose models might yield suboptimal performance. For domain-specific DH tasks, such as topic modeling or word embeddings, using existing Chinese segmentation tools, employing character-level tokenization, or training custom tokenizers might often be a better choice.

[1] This is also the reason why many models are unable to tell you how many Rs there are in “strawberry.” For the machine model, “strawberry” is just a single merged token, while humans can move dynamically between different levels of granularity (letters/words, e.g.).

Thanks for this insightful post! I have the feeling that it’s only an issue for modern Chinese. For ancient written Chinese, the tokens in the vocabulary are mainly single characters.

What if the BPE-style approaches are only addressing languages that have declesion? Entity recognition which involves context understanding should be delegated to later stages instead of being carried out during tokenization.

But again, these tokenizers are indeed problematic, given that the models are able to demonstrate very good capabilities, there must be a way to utilize what they’ve learned to help build better tokenizers. That might give us more insight as well.