While not readily apparent, the New Testament Virtual Manuscript (NTVMR) room has an API that is publicly accessible. An API, or Application Programming Interface, allows users to interact with an application and its data programmatically. If you were to look at the NTVMR, you wouldn’t find any button that leads you to the API. However, in Troy Griffitts’ Doctoral Thesis on the creation of the NTVMR, which can be found here, he has a chapter covering the API behind the website. In this chapter, Troy explains the structure and usage of the API and writes, “The VMR Web Services API layer is primarily useful for exposing the functionality of the VMR to other research projects wishing to access the functionality or contribute to the dataset through their own systems and tools.”1 He provides a link to the API in this chapter. You could also find the API by googling “ntvmr api” and for me, it is the first result given. In this post, I will introduce you to some parts of the API and provide some ideas for how the data behind this API could be leveraged for possible avenues of research.

Downloading Transcriptions

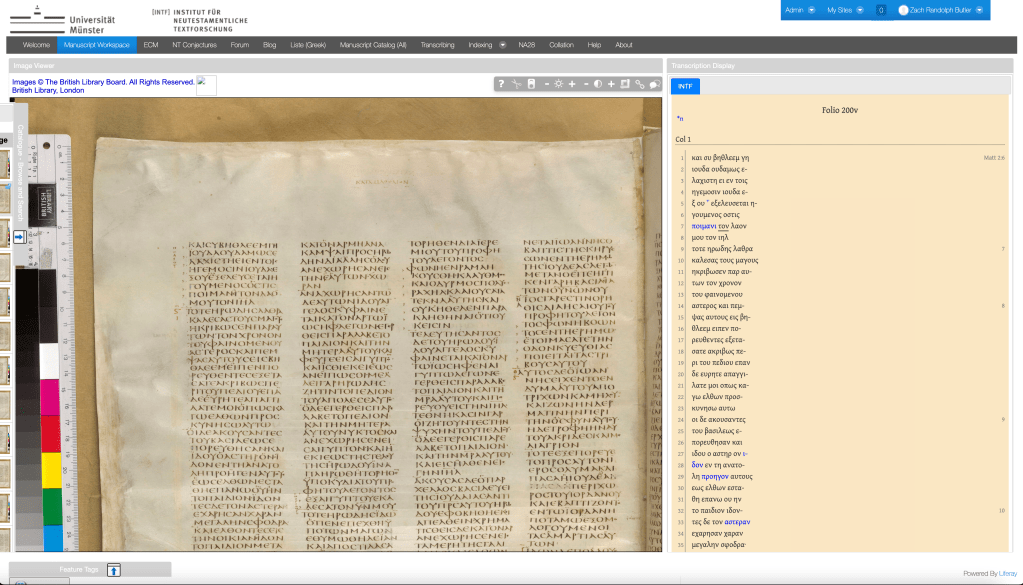

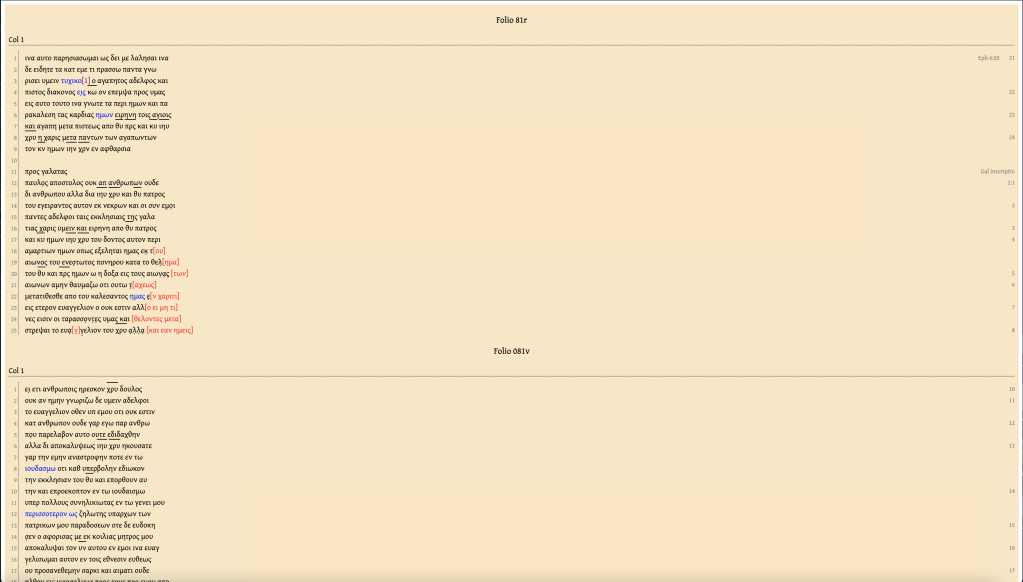

The most common task I utilize the API for is downloading transcriptions. The NTVMR does not have a button for users to download an entire transcription, let alone several full transcriptions of manuscripts. This is true regardless of whether the transcriptions were made by you or someone else. The NTVMR will display published transcriptions by the INTF alongside manuscript images as long as those transcriptions are available. These transcriptions have a Creative Commons License.

As I have explained in a previous post, these transcriptions are just XML files. There are links for TEI or HTML at the very bottom of the transcriptions displayed next to these images, and if you click on TEI, a new tab will open in your browser displaying the XML underlying the transcription. This tab will only contain the XML for that single page. What if I want the XML for the entire manuscript? What if I want to download more than one transcription for several manuscripts for further analysis? This is where the API can help!

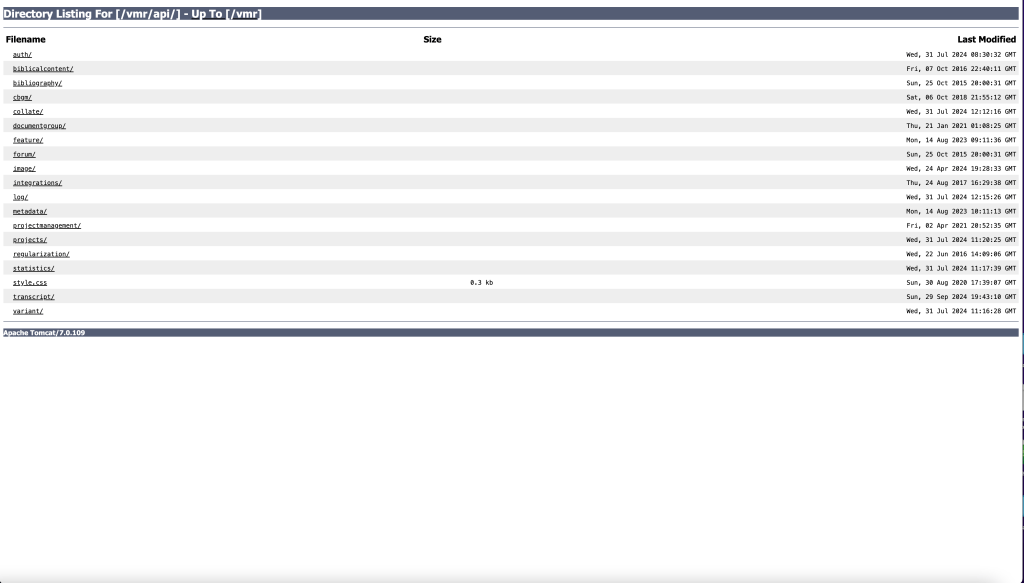

If you were to visit the link of the API shared above, you would be greeted with a webpage containing several items. This post will not be able to explore every option listed in the API, but I will highlight a couple, including how to download transcriptions.

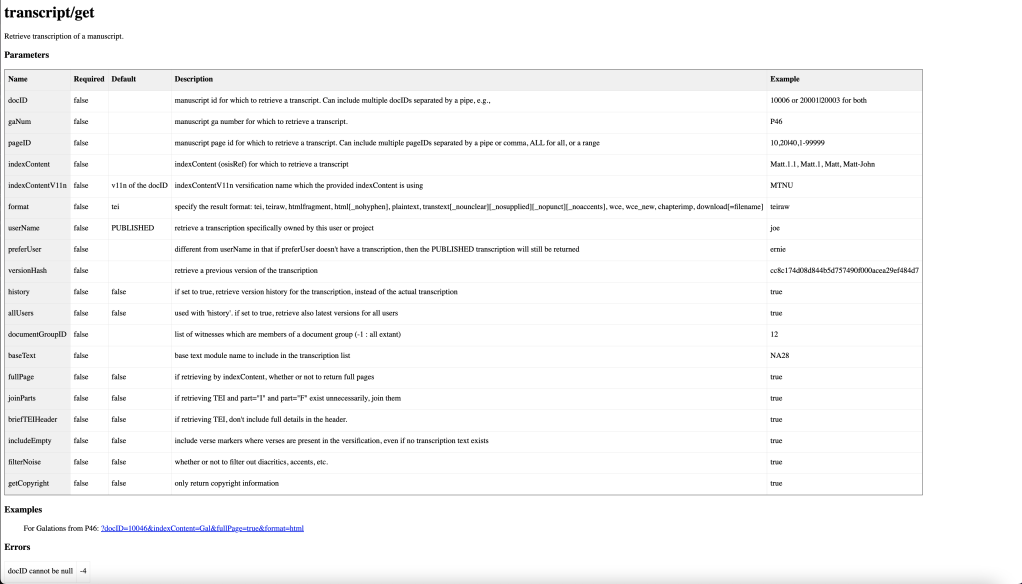

Clicking on “transcript/” and then “get/” will lead you to a webpage that contains a table with key and value pairs that can be added to the URL. There is a short description of what each key does and the kinds of values that can be passed into it. There is also an example at the bottom of the page of what you could add to the base URL of the page.

You add a question mark at the end of the URL and add any key you want with an equal sign between it and the value. Each key must be separated by &. To try out the example given by the API, you would copy ?docID=10046&indexContent=Gal&fullPage=true&format=html and paste it at the end of the URL and press Enter. This URL would give you the full transcription of Galatians in P46 in HTML format in a new tab.

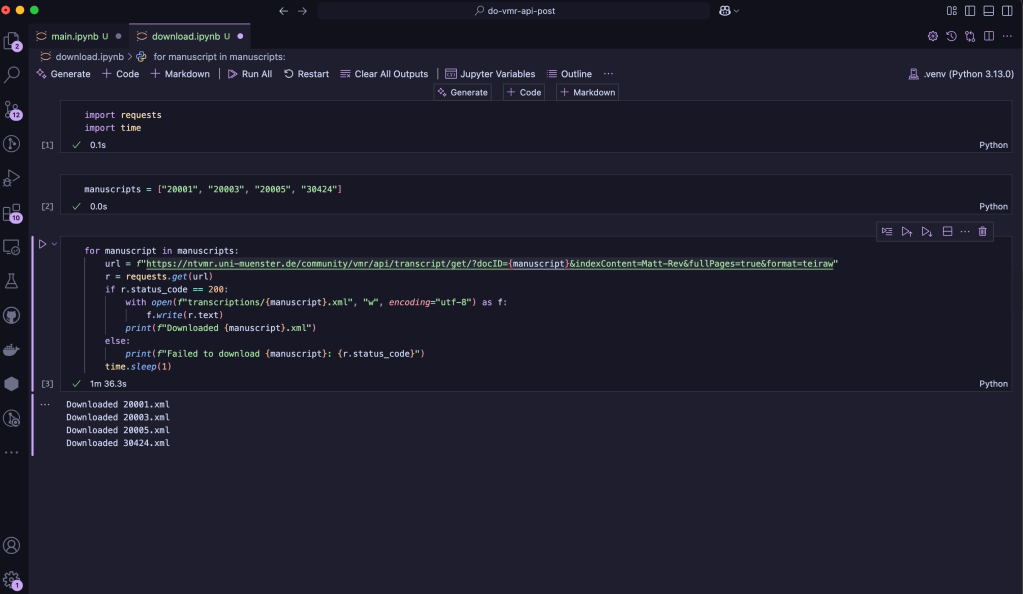

But what if I wanted to download several full transcriptions for further analysis? For instance, I have been working on analyzing the punctuation in a handful of manuscripts that I hope to write about in a future post. I am interested in the punctuation found in 01, 03, 05, and 424. I could write a quick Python script to download the transcriptions for all of these manuscripts by making calls to the API.

I simply put the manuscripts I am interested in inside a list and loop through it. Using the requests library, I make an HTTP request for each manuscript for transcriptions of Matt-Rev, and I specify the format as teiraw because I want the XML to do further analysis with Python. One important thing to note is that I added a one-second pause between iterations of the loop. This is important because I may or may not have overloaded the server the first time I did this. A full transcription of the entire New Testament can be quite large, and downloading several can cause strain on the server. Don’t be like me and play nice with the server so other users don’t lose access to the NTVMR! I downloaded all the transcriptions I needed in just thirteen lines of code.

Analyzing Metadata

Another way to leverage the API is to harvest and analyze the metadata associated with manuscripts. The NTVMR is also home to the digital Liste, a catalogue of all Greek New Testament Manuscripts. This catalogue contains all sorts of helpful information, like the date, location, content, bibliography, etc., associated with a manuscript. The API provides access to all of this information.

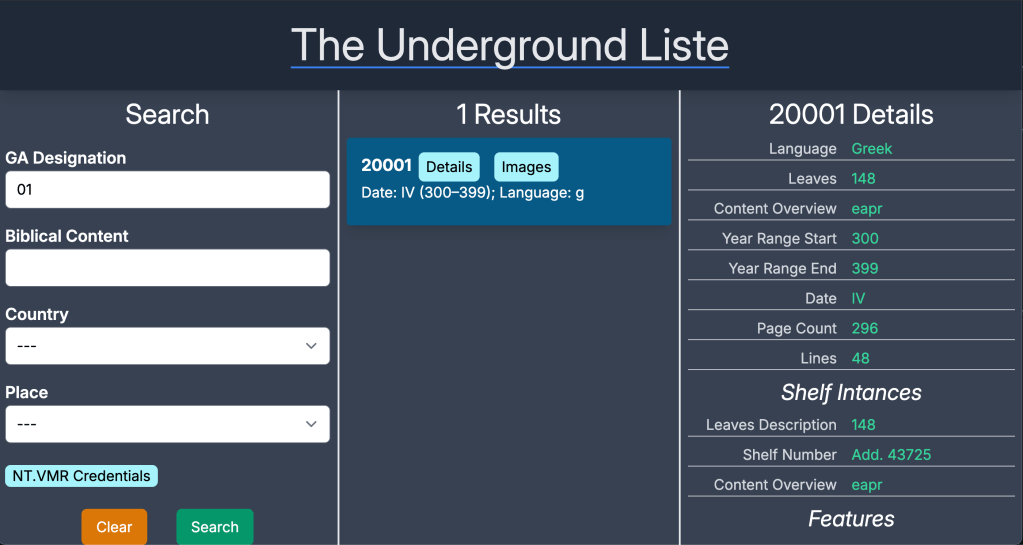

The UndergroundListe

David Flood, the creator of Criticus, an app I wrote about in a previous post, has utilized this data to clone some of the functionality of the NTVMR. The NTVMR allows users to look up manuscript information in the Liste and to view images of manuscripts. The NTVMR has much more functionality than this, though, and simple tasks like looking up a manuscript can be slow while the web app loads all of the pieces of the application. David leveraged the API to create a web app at https://undergroundliste.com/, allowing users to look up manuscript info and view images. His app is faster than the NTVMR because it only does one thing and is very lightweight.

This tool is super helpful, quick, and mobile-friendly. If all you need is quick information or access to an image, https://undergroundliste.com/ is a better alternative to the NTVMR. He has even provided a place to input your credentials in case you have been given access to images that are not available to the public, and he does not store or save these credentials. They are passed as variables in the API.

Visualizing Data

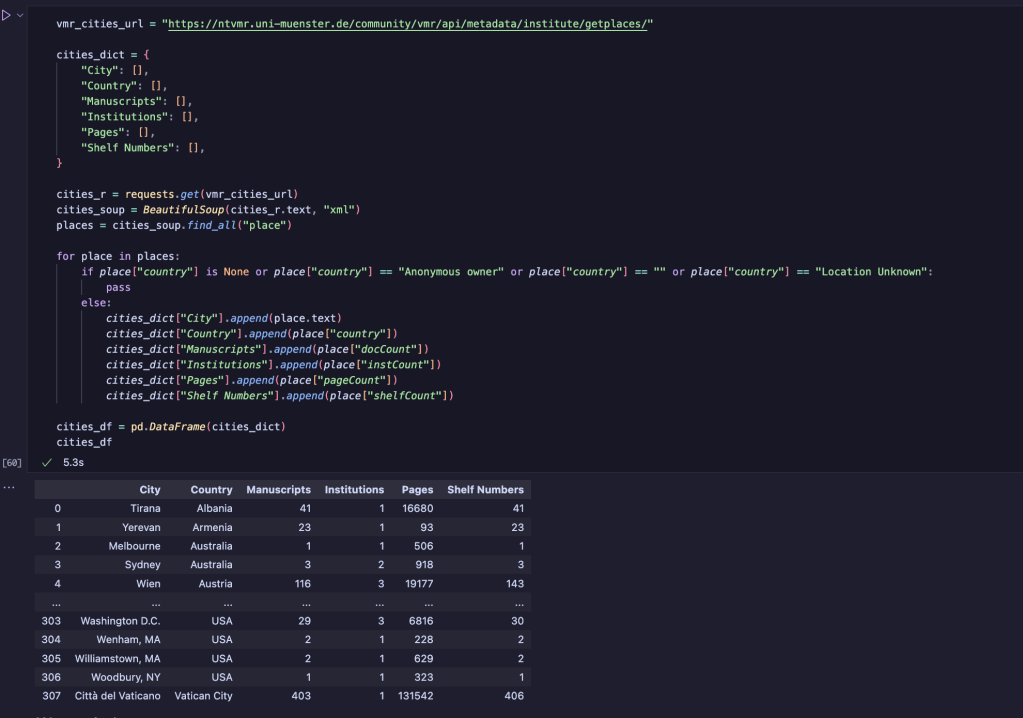

I wanted to try my own hand at utilizing this data by visualizing where manuscripts are held globally. After navigating around the API I found that if I select “metadata/”, “institute/”, and then “getplaces/”, a new tab opened up in my browser with a list of cities in XML format that contains information like the number of manuscripts and pages of a manuscript that are located in that city. I could use Python to process this XML and convert the data into a dataframe.

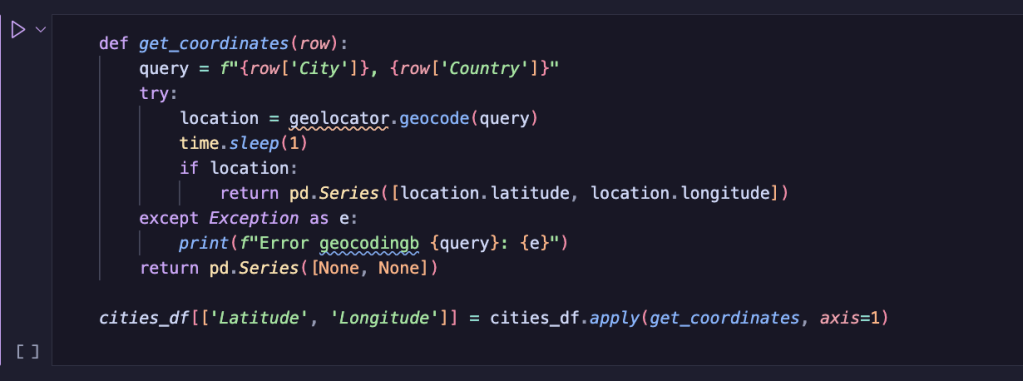

In a very short block of code, I was able to accomplish just that, filtering out some of the items that do not have a location. The next step is to create a map. After a quick Google search for Python geographic visualization, I ran across Folium. Folium is a Python library that allows you to create a map with all sorts of pinpoints and markup that plays well with a Jupyter notebook. However, Folium needs coordinates to work, and my data is missing the longitude and latitude for each city. After another Google search on how to obtain coordinates for locations with Python, I ran across Geopy. In another short block of code, I wrote up a function to get the coordinates for a location and added it to my dataframe.

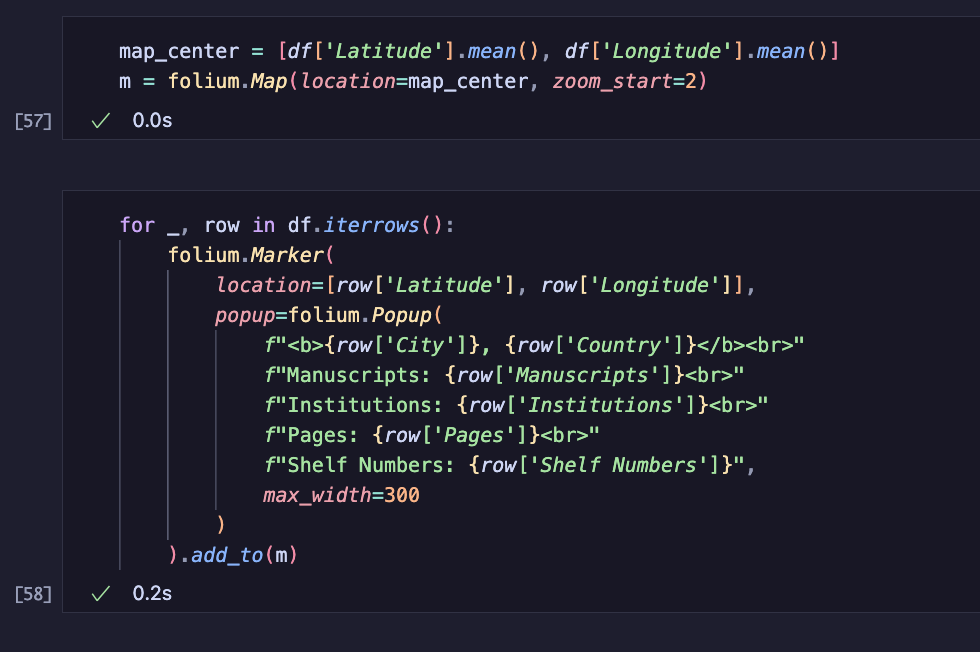

All that’s left is to create the map and pass these coordinates into it to create points to be marked. Folium also allows you to add additional text or data to the point that is displayed when a user hovers over the point with the mouse. The data about the number of manuscripts and pages could be used for this.

And voilà, a map is created that users can zoom in and out of, showing all the places on Earth that house New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Hovering over any point displays some additional information about what can be found there. Creating something like this manually would be painstaking and take a long time. I automated all of this with just a few blocks of Python code!

This was just a small taste of what is available and possible using the NTVMR API. I hope this post will spark ideas of your own for analyzing and building tools that make use of this data. In my next post, I plan to demonstrate the results of my research on the punctuation found in the manuscripts I downloaded at the beginning of the post.

- Troy Andrew Griffitts, “Software for the Collaborative Editing of the Greek New Testament” (University of Birmingham, 2017), 258. ↩︎

One of the primary issues with the NTVMR API is that (1) it is decently well-hidden on the site and (2) the documentation leaves much to be desired. I wonder how much more use researchers could get if they better understood the tools that they are given?