What is Sinorelic?

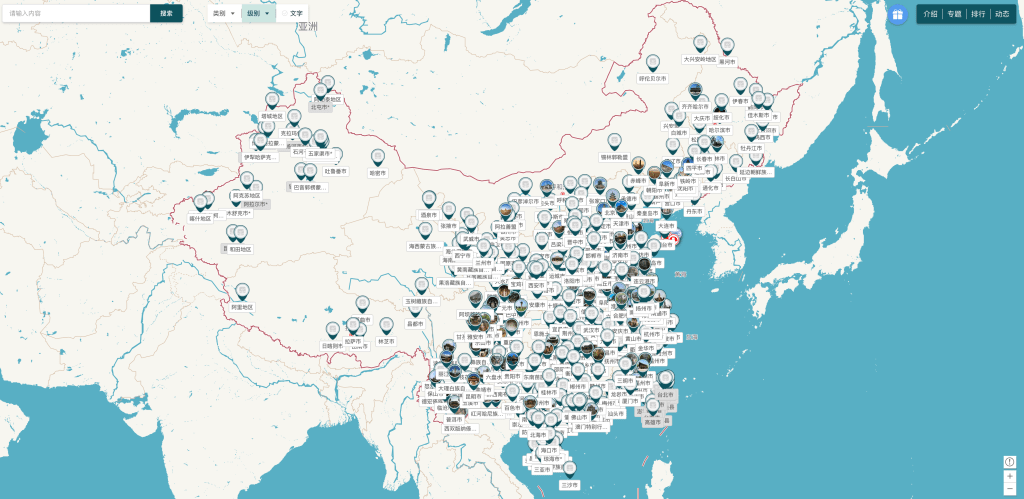

Sinorelic (华夏古迹图) is a Chinese-language online platform for collecting and sharing data about cultural heritage sites. Developed by Nanjing Huagu Keji Ltd., Sinorelic’s website and app are designed around an interactive map, which provides a geospatial database of photographs and historical information about thousands of national, regional, and municipal-level cultural heritage sites from Guangdong to Heilongjiang. When a group led by Shao Shihai (“Lao Shao”), Wang Teng, and Liu Xiaoping initiated the project in 2014, it concentrated on sites in the area around Nanjing and has since expanded to include cultural heritage sites throughout Mainland China.

Throughout, two objectives have remained at the center of the platform’s mission, which, according to the website, is to “provide information and awareness about cultural preservation for enthusiasts.” Sinorelic’s interactive map is free to browse, and registered users (for the moment, a Mainland phone number is required to register) also have the ability contribute entries for new sites, upload their own photographs and comment on existing entries, and even assume leadership roles in local communities of enthusiasts and researchers. Sinorelic is thus different from many digitization projects begun by government agencies, international teams of researchers, archives, or museum collections, because it relies on crowd-sourced information—a bit like social media meets collaborative wiki.

How does it work?

Sinorelic provides information about sites related to architecture, tombs, caves, and sculptures, as well as historically significant modern and contemporary sites. On the page of the interactive map of cultural heritage sites, visitors can either roam through the map or search for sites in a specific city. Searches within cities can be narrowed further by type of site (类别) and by administrative division (级别).

A virtual visit to the region around Suzhou, Jiangsu province shows a total of 734 sites, 75 of which are cave temples or stone carvings (石窟寺及石刻). Pages for specific sites generally provide basic information about the date of the site’s construction, its location, and any entrance fees. Pages also include basic historical information akin to an entry on Baidu Baike (the largest Chinese-language collaborative encyclopedia, similar to Wikipedia). For example, in Suzhou’s city center, we find a page for the Yuan-era (1279–1368) “Stele Commemorating the Meritorious Deeds of Zhang Shicheng” (张士诚纪功碑), a rare example of a commemorative relief sculpture. The historical introduction for this entry, like most entries on the platform, is light on citations, but it does point out that modern scholar Jin Songcen 金松岑 and others have interpreted the stele to represent the local warlord Zhang Shicheng receiving a diplomatic visit from a Yuan envoy.

Interestingly, the bottom of this site’s page shows one way that users collaborate to modify content on the platform. Here, several users have noted corrections to the information on the page regarding the specific location of or historical information about the stele. In the gallery, users’ photographs provide visual information about stele’s setting and details of its relief carvings. Conceivably, similar sites with steles or other inscribed materials could be a boon for epigraphers, if a visitor to the site has snapped a legible image of the stele inscription or cliff carving.

Although anyone doing scholarly research on these sites should consult the standard references, like Collected Maps of Cultural Relics in China (中国文物地图集) and Tsinghua University’s more recent series Maps of Ancient Architecture (古建筑地图) as well as relevant secondary sources, the advantage of Sinorelic is that it regularly provides a greater amount of visual information about a site than printed publications would. Its entries also include images—of decorative bases and sides of stelae, of sculptures at dusk, or of miscellaneous explanatory plaques—that are often excluded from scholarly monographs and reference books, either due to publication costs or because such images are considered secondary or tertiary concerns in historical studies of a site. The Feiying Pagoda (飞英塔) in Huzhou, Zhejiang province, for example, has been photographed extensively from the interior, providing details of its unusual ‘pagoda within a pagoda’ as well as plaques installed at the site that explain its modern excavation and reconstruction.

Ultimately, the information that Sinorelic provides is a product of what the visitors to these sites have found noteworthy and accessible. As a result, major sites in urban areas have accumulated the most photographs. For example, several pages of users’ photographs now accompany the site of stone carvings at Feilai Peak (飞来峰), near Hangzhou. Still, several smaller sites located beyond major hubs, which can be difficult to physically access even in the best of times, have pages on Sinorelic. See for example, the Song-era (960–1279) spirit path of Yeshi Taijun 叶氏太君, east of Ningbo, Zhejiang province. Often, users’ photographs of these sites are not only useful for conducting iconographic studies of sculptures, but also reveal something of the experience of the site. Many visitors, for example, have photographed sculptural niches in raking light or at different times of the day. An additional advantage of Sinorelic is that museums are also considered sites and often have their own pages. There, visitors to the platform can sometimes find photographs taken of objects on display in museum exhibitions.

Rethinking fieldwork?

Sinorelic can serve as an extremely convenient resource for anyone wishing to see details of sculpture and architecture and study the geospatial relationships of sites. Although I might not be the “enthusiast” the founders had in mind when they developed this platform, I’ve found Sinorelic immensely useful both for running quick checks on architectural and sculptural sites and for learning about new sites. Perhaps, in an era of postponed, restricted, and shifting travel plans, what I find in Sinorelic is also the joy of “access” to these sites. While widespread efforts to digitize museum collections and archives continue to enhance the accessibility of the study of Chinese material culture, information about the largest body of visual sources—sculptures, inscriptions, architecture, and other materials located in situ—remains scattered or inaccessible. And the old axiom that researchers must “get to the field” maintains its foothold within studies of material culture. Can Sinorelic, with its apparatus for user-generated content, offer a model for rethinking fieldwork?

To be fair, this question is not one that the platform was designed to take on. Still, as resources like Digital Fieldwork with roots growing from pandemic experiences in a wide range of academic fields emerge to aid scholars and graduate students, especially those conducting archival research and interviews, “get to the field,” new questions about the effectiveness and legitimacy of digitization projects will follow. These resources, explicitly or not, challenge conventional assumptions about the necessity of in-person fieldwork in a world concerned increasingly with issues of accessibility and the costs (financial, environmental, or otherwise) of international travel. At the moment, Sinorelic’s lack of cited secondary source information and general complications surrounding the use of images published by other users makes it an awkward fit for researchers wanting to use the platform for something other than a quick check. But as issues surrounding accessibility become increasingly relevant, the potential of user-generated and collaborative platforms like Sinorelic, which might help us reimagine longstanding scenarios for conducting formal analysis in situ, must become part of the conversation.