This is a guest post by Joanne Bernardi.

Overview

This post introduces a series on digital pedagogy, specifically, designing and implementing collaborative digital assignments and related hands-on classroom practices in the humanities and humanistic social sciences. This series is partly motivated by What We Teach When We Teach DH: Digital Humanities in the Classroom (edited by Brian Croxall and Diane K. Jakacki, 2023), a recent addition to the Debates in the Digital Humanities series, with contributions that re-center the role of teaching in DH discourse to underscore its growing importance to the field over the past twenty years. The book’s layout, with separate sections on teachers, students, classrooms, and collaborators, argues that teaching is shaped “not only by disciplinary training” but also by our “students, surroundings, and institutional infrastructure,” factors this series will take into consideration as I share my own experiences adopting DH strategies to revamp and recharge course assignments and objectives. DH-based in-class assignments, for example, provide novel opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration. Semester-long DH course projects can blur distinctions between research and teaching as students become “co-investigators” on large-scale and/or ongoing research projects that apply technology to facilitate or amplify humanistic intellectual inquiry.

I mostly teach interdisciplinary elective courses variably cross-listed with Japan Studies, East Asian Studies, Film and Media Studies, Digital Media Studies, Visual and Cultural Studies, English, History, and Art & Art History. My students include undergraduates and a smaller number of graduate students who bring their training in these disciplines into the classroom, and undergraduate science and engineering majors who need to fulfill Humanities requirements. The digital assignments I’ve designed (and continue to tweak) for these courses have a low learning curve and can be easily adjusted to accommodate other disciplinary objectives. Many colleagues working outside my own immediate areas of study have helped me design, develop, and implement these assignments. Notably, I did much of the work re-configuring coursework (adding DH assignments that are more effective and creative, for example) in online course development workshops during the pandemic.

In subsequent posts, I’ll detail the objectives, step-by-step processes, benefits, and challenges of using digital tools for the following types of collaborative group assignments: (1) multimedia annotation (formal film analysis and/or identifying and contextualizing archival films; (2) geospatial mapping (creating socio-historical contexts and/or visual and narrative analyses of genre film); and (3) digital curation (working with a digital archive of multimedia objects and object analysis). In each post, I’ll suggest possibilities for modifying assignments so they can be used with other course materials or in courses with a different focus. I welcome comments or follow-up posts by readers who adapt my assignments for their own use and posts that document trial-and-error experiences in prototyping new strategies in digital pedagogy. Sharing DH classroom experiences in this way can help us rethink the meaning and purpose of applying technology in our teaching and research. It can also remind us of digital pedagogy’s potential to help create new pathways for transdisciplinary and comparative collaborations across linguistic, temporal, and spatial boundaries.

A brief outline of the series

Several years ago, I started identifying courses I teach on a regular basis and experimenting with replacing their more conventional essays or research papers with collaborative, semester-long digital assignments. Because each course I teach has a different focus and unique materials and objectives, I ended up with a range of assignments that help students critically and creatively engage with core issues while using course-appropriate (and easily accessible) tools and methodology. I discovered that after two or three iterations of a course, it became easier to parse semester-long assignments into discrete steps that could be more coherently scaffolded into the syllabus. I also continuously work on clarifying the instructions for each of these assignments and the way I communicate the value and purpose of using different types of technology to achieve course objectives. In this series, I’ll draw on this experience, offering guides for the targeted use of specific digital tools, platforms, methods, and practices. I will also include relevant resources and general news on DH pedagogy in future posts. What follows are brief outlines for each of the digital applications, tools, or platforms that I use in the digital assignments I’ll introduce in this series.

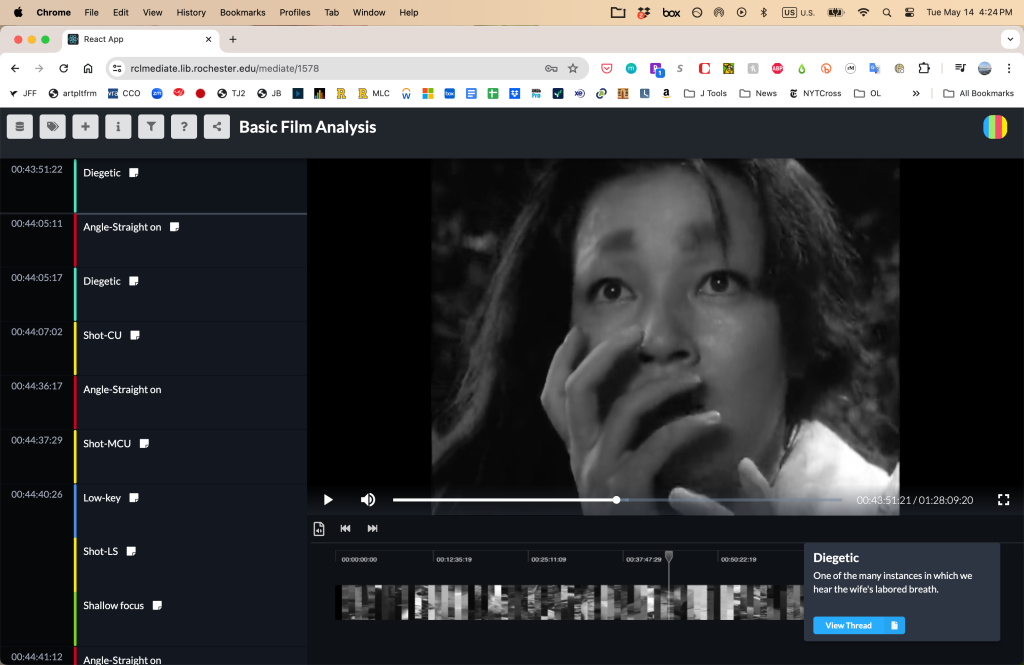

Mediate

Mediate is an open-source platform for annotating audiovisual media developed by University of Rochester faculty and colleagues from the university’s Digital Scholarship team. This user-centered, web-based platform allows users to annotate time-based multimedia content for individual research or group projects. Audio or video digital media can be uploaded to Mediate so users (e.g., students) can annotate selections using automatically generated markers and real-time notes. These markers can be organized according to a customized schema designed for the media format used and the project’s targeted objectives. After completing their annotation, users have exportable data they can use to generate visualizations based on their observations, further analyzing their interpretations of media content. I use Mediate successfully to teach formal film analysis and film style (students say they’d rather learn the “how and why” of film technique by using Mediate’s hands-on annotation features instead of memorizing glossary terms they call out in class, or jot down while viewing or listening to course material). Notably, students also use Mediate to research, identify, and annotate digitized archival film footage and other cultural heritage objects, enriching them with layers of geographical and socio-cultural contextualization. This is the only tool in this list that might be unfamiliar to readers.

ArcGIS StoryMaps

Most readers are probably familiar with ArcGIS StoryMaps. This GIS mapping tool is a useful aid in location-based learning that grounds course content and projects in space and history. Students develop critical skills by creating visual- and text-based analyses of course material while contextualizing data and thinking and writing critically about space. I use ArcGIS StoryMaps in a course on Godzilla and other kaiju genre films that requires critical comparisons of different release versions of a single title (e.g., the original vs. dubbed or subtitled foreign releases) and familiarity with reception theory. The course’s main assignment is a multi-step semester-long group project that results in a spatial analysis of the networked relationships between film events, central characters (including Godzilla or another kaiju in the Godzilla “monsterverse”), and the film’s narrative (diegetic) landscape, Japan’s historical (nondiegetic) landscape, and contemporary locations. Because the trope of “Where is Godzilla now?” is central to every Godzilla film, and Godzilla’s incursions into Tokyo’s post-World War II landscape have intrinsic meaning, students learn how spatial analysis can trigger a more intimate and immediate understanding of the tensions between a film’s synchronic and diachronic reception, and how an individual film’s anti-war or environmentalist agenda can shift in correlation to differences in marketing and exhibition contexts.

Omeka (and Omeka S)

In an earlier Digital Orientalist post, I introduced the relationship between “Re-Envisioning Japan: Japan as Destination in 20th Century Visual and Material Culture,” an open-ended DH project that encompasses a digital archive that doubles as a research and teaching resource, and this project’s companion course, “Tourist Japan.” I started teaching “Tourist Japan” in 2002, inspired by a growing collection of Japan-related travel, entertainment, and educational ephemera. In 2013, I used objects in this collection to design a collaboratively built digital archive. This expansion into digital space prompted me to “re-envision” my focus and original syllabus for “Tourist Japan.” The following year, I taught the course with an almost entirely new syllabus. In 2017, I migrated the prototype digital archive, built in WordPress, to an Omeka platform because of Omeka’s increased flexibility. I designed “Object Encounters,” an object analysis assignment that could be built in or linked to Omeka. The relationship between “Re-Envisioning Japan” and “Tourist Japan” exemplifies the blurred distinction between DH research and teaching that I mentioned earlier. Over the years, students in “Tourist Japan” have contributed to “Re-Envisioning Japan” by creating “Object Encounters” (visual explorations of objects with minimal narration, informed by material culture methodology). They also learn how to create metadata they add to Omeka’s Dublin Core interface, bringing them a step beyond “student status” to become research partners and project collaborators.

The next post in this series focuses on creating assignments using Mediate. This summer, I’ll interview Joel Burges, the head of Mediate’s development team, to learn more about how the platform is being used in Linguistics, Musicology, and Film and Media Studies courses.