Shuge 書格 is a free, online database of Chinese rare books, which offers a continuously expanding collection of high-quality scans for download. In a previous post, editor Maddalena Poli introduced Shuge, describing the website’s origins and its collection of “traditional books” (傳統部分). Shuge’s main function is to collect information from other digitized resources, drawing from sixteen libraries and eight museums in East Asia, Europe, and North America. The website’s appeal lies in how it arranges these resources, as well as its information about the books’ production dates, size, format, design, prefaces, and collectors’ seals, for research or teaching purposes.

This article introduces Shuge’s “special collections” (特殊類別) section, which includes examples of paintings, illuminated books, calligraphy, rubbings, maps, and photographs. At the outset, it is worth noting that Shuge is slightly unique among digitization platforms for combining these special collections with its collections of manuscript and printed books, since the former are often thought of as “museum objects” and, so, categorized separately. The entries in these special collections are strongest on well-known Chinese handscroll paintings, illuminated books, and Tokugawa-era (1603–1868) Japanese handscrolls. Other works in the photographs collection, such as a collection of slides used in an introductory course on East Asian culture and history at Harvard University taught for many years by John K. Fairbank and Edwin O. Reischauer, are perhaps less well-known to global visitors and a reminder that, increasingly, current digitization projects must contend with ‘re-reproduced’ technologies like slides.

As with all projects aimed at digitizing visual materials, Shuge’s focus is on offering high-quality reproductions. For the most part, these reproductions can be accessed for download as PDFs, which, for illuminated books, take the form of open page scans and usually include images of the cover page and of pages with marginalia. An album from the studio of the early nineteenth-century painter of export paintings, Fatqua, for example, provides high-quality reproduction of the album’s forty-six leaves, Painted Album of House Furnishings and Their Arrangement (家具陳設畫冊) that allows for close viewing of details.

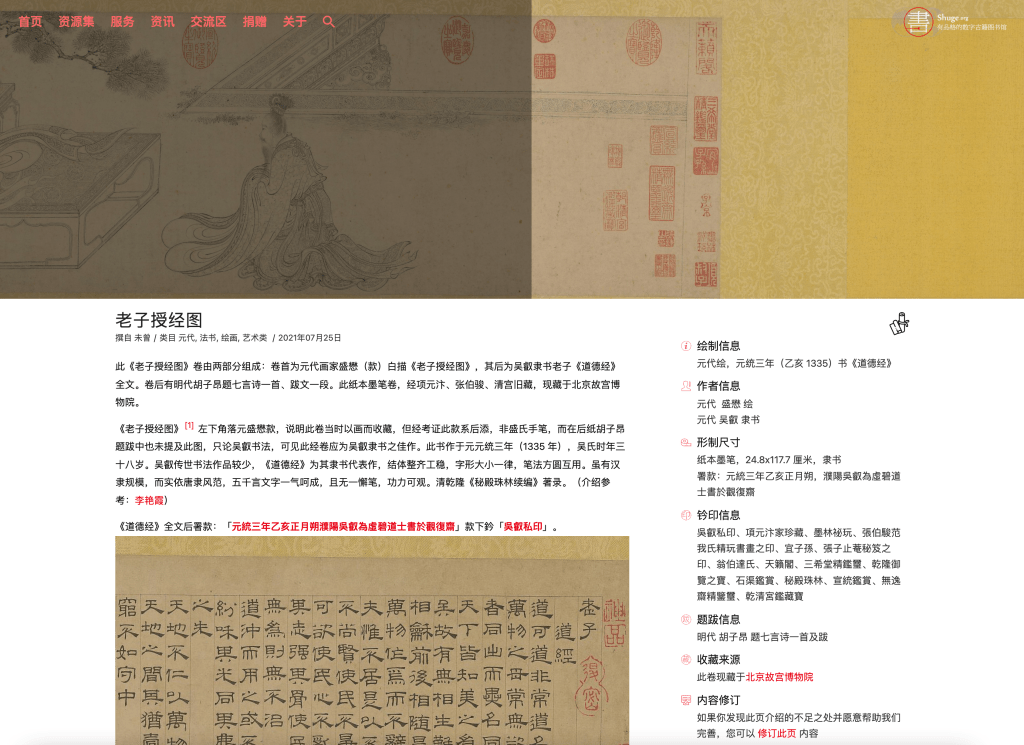

The website also allows for the digital reunion of scattered sets of paintings. For example, the set of eleven hangings scrolls of The Sixteen Arhats (十六羅漢圖), which now exists in two Japanese collections in Tokyo and Gunma Prefecture, are presented as a single entry. Although Shuge’s entries on paintings are not as numerous as its “traditional books,” many of the website’s entries on handscroll paintings also provide transcriptions of colophons and seals, which offer indispensable information about the social history of the works. For example, in the entry on the fourteenth-century handscroll Laozi Conferring the Daodejing (老子授經圖), the website provides transcriptions of the sixteen collector seals on the painting. In this entry, the website also includes reference to premodern collection records related to the painting, such as the Pearl Forest of the Secret Hall (秘殿珠林續篇), a record of Buddhist and Daoist paintings in the imperial collection during the eighteenth century.

As seen in the image from the same scroll of Laozi Conferring the Daodejing above, it appears that Shuge is also beginning to provide a type of simple image annotation on several paintings. In this case, the location of an inscription is marked with the number “1” and a tag attributing the painting to Sheng Mao (盛懋子昭畫). If used more extensively and consistently across both the special collections and traditional books, such image annotations could provide an analytical tool that even in-person viewing of materials cannot replicate (akin to the image annotation tools explored in Yale University’s “Ten Thousand Rooms Project”).

These image annotations also alert us to some of the possibilities, and challenges, of staging online collections of visual materials. Increasingly, the most salient issues in digitization projects that focus on visual materials involve not only what but also how to digitize. In contrast to text-centered digitization projects, which tend to focus on the accuracy of information and results-oriented search features, image-centered projects have come to be concerned primarily with interface, confronted as they are with issues of how to translate the visual experience of works to digital formats.

One way that Shuge addresses these issues in its special collections is through the “comparing editions” (對比瀏覽) viewer function. With this function, viewers can look through two extant editions of the same handscroll composition, side by side. For example, in the entry on the Ten Views from a Thatched Hut (草堂十志圖卷) handscroll, which exists in two compositions in Taipei and Osaka collections, visitors can compare both handscrolls in the same digital viewer. Similar interfaces are beginning to be explored in other image-centered digitization projects, such as the “East Asian Scroll Paintings” project at the University of Chicago’s Center for Art for Art of East Asia, which, aims to “simulate the experience of viewing handscrolls in ways that published photographs in books and projected slides cannot.” To this end, both Shuge and the East Asian Scroll Paintings project use a similar viewer technology, based on the Seadragon Javascript image viewer, “HandscrollViewer” (although the EASP viewer includes additional functions, such as horizontal auto-scroll).

As has been noted many times since the digitization of visual materials first became mainstream, with digitized artworks, what we gain in visual details and convenience of access, we lose in the experience of an artwork’s weight, scale, and other sensory information. Premodern artworks, it goes without saying, were not designed to be viewed on computer screens (or even in glass display cases), and so curators of digitized visual materials must constantly wrestle with the tension of placing objects into contexts for which they were not intended. In some ways, this tension is doubled for handscroll paintings and books—being kinetic objects, they require handling and movement to be experienced.

In the relatively nascent world of digitizing artworks and books, much of the most successful technologies of digitization attempts to account for this quality of experience by communicating the physical nature of objects (it is for this purpose, for example, that the British Library developed the “Turning the Pages” interface in 1997, which combines curatorial commentary with an interface that allows viewers to zoom in and ‘turn’ the pages of digitized books). Projects working in this direction have focused on trying to recreate the same experience of an in-person viewing, through interfaces like the handscroll viewer. Websites like Shuge, however, also have the potential to move beyond simply reproducing either content or in-person viewing experiences, and to continue probing the ways that we interact with digitized images. Through newer interface tools like image annotation, websites like Shuge are beginning to explore the potentials of what is unique about digitized viewing experiences, and how these differences can lead toward new forms of engagement.