This week’s post was written by Tomasz Sleziak. Sleziak is a scholar in Korean studies (particularly Korean but also global Confucianism) and Post-Humanism, conducting research on Confucian socio-legal and metaphysical discourse throughout Korean history, as well as its placement within the global discourse on Post-Humanism, Trans-Humanism and Non-Humanism. He completed his PhD in Korean Studies at London’s SOAS after having achieved his Master’s Degree at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland jointly with research in Seoul at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies.

The predominant writing system of the modern Korean Peninsula is called Hangeul, originally named by King Sejong (1397-1450) as “Hunmin Jeongeum” (virtuous sounds for educating the people). Hangeul is considered relatively easy to learn, and even in international contexts (including teaching) is favorably compared with Chinese or Japanese characters as far as simplicity is concerned – the complexity of Korean grammar and speech forms notwithstanding. The major “snag” behind this approach becomes apparent when foreign learners of the Korean language attempt to study based solely on written materials (for example, in the absence of a native Korean teacher), or whenever one is confronted with sounds that do not exist in one’s mother tongue. Usually, either of the two approaches for conversion of one language system into another is used: Romanization or transliteration. The former involves representing sounds of one language through another’s writing system (pronunciation-based), and the latter indicates more direct 1-1 transformation of one written script into another (spelling-based). In many ways, however, the actual particulars of these two strategies frequently overlap. At present, three systems of Romanization or transliteration are prevalent in day-to-day Korean language communication and in academia. These systems are: McCune-Reischauer (henceforth the MR), the Revised Romanization of South Korean Government (henceforth the RR), and Yale. They have been devised based on different rationale, and none of them simultaneously provides seamless international communication and provides respect to the original Korean spelling of Hangeul-constructed words. In this short piece, I will describe the main features of the three transliteration systems briefly, with particular focus on their characteristics which are especially pertinent to the modern non-Korean users of internet technologies as well as scholars involved with any aspects of Korean language and culture. However, the methods of transliteration within the confines of Korean culture warrant a brief exposition beforehand.

Comparison of Romanization systems for stop consonants from Charles B. Chang’s “First language phonetic drift during second language acquisition,” p. 118.

The Classical Chinese Hanmun script (the lexical and symbolic structure of which virtually stalled at the beginning of the Song dynasty in the 10th century AD) was by default deeply incompatible with grammar structures of Korean language and its spoken forms. Consequently, its use had been mainly constrained to the upper social strata from the earliest states of the Korean Peninsula – historically, it became most prevalent from the United Silla (600CE-932CE) era onward. Even among these echelons of society, the use of Classical Chinese for administrative purposes necessitated the use of grammar particles common to the Korean language, but which the Chinese lacked; these “connectors” would be inserted into the text in relevant places and were derived from the Chinese characters that were pronounced in a manner similar to Korean particles. When Hangeul was invented by king Sejong and his associate scholars, these particles took the form of the native script. This complex system of quasi-transliteration was called Gugyeol.[1] A second major system of communication in pre-Joseon Korea was the Idu, in which Chinese characters were arranged in sentences based directly on Korean grammar. This system was in particular used by low-rank administrative clerks (ajeon or hyangni) and key members of the middle stratum (the jungin); both of these occupational groups may be considered “technicians” of Joseon era, without which the state apparatus likely would not function, and whose expertise and interests provided major impulse for modernization as well as facilitated international communication from the 17th century onward, yet whose formalized status was low or ambiguous. In the modern era, these mixed forms of writing evolved into a more “nationalized” system (with clear delineation of native and Sino-Korean vocabulary, and more directly based on daily Korean speech), still situationally used by South Korean academic institutions. Overall, the attempts to logically translate, transcribe or otherwise adapt the noble Chinese script to the Korean socio-political reality resembles the often awkwardly structured strivings of the Western world to firstly understand, and then possibly globalize the Korean language.

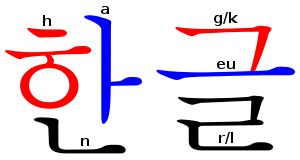

The word Hangeul with interlinear Romanization.

The MR system was devised by American scholars George McCune and Edwin Reischauer in 1939, in a pen and typewriter-dominated era. Its chief goal was to approximate sounds of the Korean language, making Hangeul in its native sounds accessible worldwide. To further this goal, breves and apostrophes are used for vowels and consonants alike to signify aspiration and otherwise differentiate between characters used depending on syllabic position and grammatical context. For example, in this system, 어 is rendered as ŏ, 오 as o, ㄱ as k (or as g if it is non-initial), and ㅋ as k’, leading to potential pronunciation issues among both the native users of the English language and other foreigners. For example, I am a native speaker of Polish language, in which aspirated consonants do not exist. As it is noted further on, Poland (since it became member of the Warsaw Pact) predominantly utilized a Russian-made system of Romanization, which approximated Korean phonology to the one of the Slavic languages. Unfortunately, the differences between the Russian and Polish languages resulted in largely garbled words such as Phenian (actually 평양 Pyeongyang; the capital of North Korea) – pronounced as “Fenian” – becoming common in public contexts in Poland, including diplomacy. Additionally, the lack of approximates for Korean 오 and 어 in the Polish language may lead to beginners in Korean language to pronounce “오” as “u,” rather amusingly bringing it closer to the Korean “우”, which in common, or “slang” speech sometimes replaces “오”, especially amongst younger generations of Seoulites. Overall, despite the apparent academic soundness of the MR methodology, one can easily imagine the problems surfacing when it is applied to the Romanization of Hangeul in the popular contexts (games, online forums, etc) of the era of internet. In fact, omission of glottal symbols has been noted as common among internet users. This is compounded by the cumbersome nature of entering the special letters using a standard keyboard – it requires insertion of symbols or the use of specially designed websites that automatically transcribe relevant words. Among such websites is the one designed by the University of Busa, aiding in conversion between Hangeul and different forms of Romanization.

The second system of Romanization is Yale, designed by linguists from the namesake university a few years after the MR. It is highly technical, and aims to reconstruct morphemes in Korean words. It does not take account of the actual use of these words in daily life contexts, and is not intended for teaching the practical use of the language.

The last system of Romanization is called the Revised Romanization System of the Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Culture. It was proclaimed in the year 2000 with the goal of abolishing the diacritic symbols from the MR system which had been used in South Korea until then. With the rapid technological growth of the “East Asian Tigers” and increasing popularity of internet communication, as well as online gaming in the wider region, the accessibility of Korean language for wider audiences would be enabled by the proclamation of the RR. Simplification of the aforementioned 오/어 scheme into, respectively, “o” and “eo”, arguably brought transliteration of Korean closer to its intended source and away from English language. Nevertheless, numerous issues remain, many of them being connected with the base the MR system (still used in a modified form in North Korea) has in Anglo-Saxon languages.

Korean keyboard layout.

The international domination of English led to a very few alternative Romanization systems being devised. The Kontsevich system, based on the pronunciation of Korean words (unlike MR and RR), gained popularity in the former Soviet Union and its satellite states (for example, Poland), becoming adapted to local languages. It constitutes, however, a methodological exception; students of Korean language all over the world typically have to go through printouts constructed with English rules in mind to get an initial understanding of Hangeul’s pronunciation, unless they have a native-speaker teacher or a suitably “international” linguist-instructor accompanying their efforts. At that point, the global “literacy” in the sounds of the Korean language becomes a thinly-veiled political matter, or at the very least one in which the engagement of political institutions of South Korea plays an active role.

According to Eom Iksang’s research paper “Hangugo Romapyogibeop oe Suyongdo wa Gaejeong Banghyang”[2] the majority of the interviewed public figures, who are members of the European Society of Commerce and Industry in Korea (EUCCK) living in South Korea show preference towards the RR system, while more generally in Asia and English-speaking countries the rates of use were visibly split between MR and RR. The author notes, however, that the RR’s lack of precise rules on family names and, in some cases, the unclear guidelines on notation and word separation prevent this system from gaining popularity outside of Korea, and recommends in-depth discussions between linguists to determine RR’s and MR’s strong and weak points in order to develop a more balanced and inclusive Romanization of Korean language.

In the contexts of the digital humanities, the issue of inclusiveness and preciseness of transliteration and transcription systems is important for direct communication, preparation of databases and coding, among other purposes. Problems with coding frequently occur in relation with regional settings of one’s computer. For example, the majority of European or American PCs have Microsoft Windows installed as the default OS, with fonts and character sets required to properly display Hangeul frequently missing. This extends to some of the versions of the proprietary browsers, often necessitating downloading large updates or tinkering with drivers etc, which may be daunting depending on one’s level of electronic literacy and dampen accessibility of online libraries, readable PDF files, and official communications. Interestingly, even native Koreans experience problems with the specified subset of browsers – for example, pertaining to proper spacing.

In the end, we are left with either accessible but methodologically incomplete Romanization systems, or ones that are difficult to use for typical internet user and younger scholars of Korean language, culture and related topics. It remains to be seen whether accessibility and academic concerns can be truly balanced, as the global awareness and involvement of Korea is only to grow further in the foreseeable future.

[1] Oh Kyong-Geun, “Ewolucja Języka Urzędowego w Korei” [The Evolution of Official Language in Korea], Comparative Legilinguistics 22 (2015): 65-76.

[2] Eom Iksang, “Hangugo Romapyogibeop oe Suyongdo wa Gaejeong Banghyang” [Korean Romanization System: The Current Status and Suggestions for Revisions], Korean and Chinese Language and Culture Study 31: 1-30.